Humanity solved the “trust paradox” by going tribal — and paid a horrific price

- One of the most intractable problems for all social species is whom to trust.

- Different parts of the brain seek different solutions to the same problem — leading to the “trust paradox.”

- After kin, humanity put its trust in friends and then in tribes.

For all social species, one of the most intractable problems is whom to trust. I call this the Trust Paradox. A paradox can be defined as the contemplation of a seemingly self-contradictory statement that can help to illuminate a larger truth. As the philosopher G.K. Chesterton quipped, “A paradox is simply Truth standing on its head to get our attention.” At first glance, the question “In whom do you put your trust?” does not seem controversial, never mind paradoxical; the answer is usually agreed upon by scientist and layman alike. You trust family.

Your kin shares your blood. On a foundational level, you and your kin are one and the same. The genomes imprinted in the cells that instruct who and what you are closely resemble those of your immediate family and cousins. Kin selection—the preferential bias for those who are genetically related—was the first answer concocted by evolution several hundred million years ago and has faithfully served Earthlings ever since. The challenge is scale. When considering plants, social insects, and even naked mole rats, kin selection works predictably. However, when you scale up complexity to species that rely on meaty brains, long-term memory, and special kinds of social arrangements, then something else is needed.

The thought experiment of the Trolley Problem is a touchstone example of this challenge. Over the history of philosophy, it has evolved into a number of iterations, but is distilled to something like this: You are riding in a trolley without functioning brakes. On the current track stand five people who are certain to be killed if the trolley continues on its path. You have access to a switch that would divert the trolley to another track, but another individual stands there. That person will be killed if the switch is activated. So do you switch tracks or not?

When we are confronted with this thought experiment, we face an ethical dilemma. That’s because our nervous system, housing our massive brains, has multiple—sometimes competing—internal structures; these brain regions evolved for different functions, and thus compete for neural resources over what is the moral (or “ethically optimized”) outcome. While the high-minded “forebrain” seeks idealistic outcomes based on logic, reason, and numerical utilitarianism, the more ancient limbic system seeks to maximize principled outcomes that preserve harmony for your group, and the most core biological system seeks only outcomes that maximize your own odds of survival.

This is where the Trust Paradox comes to light. How do we solve the problem of whom to trust when different parts of our brain seek different solutions to the same problem? This is a paradox worth investigating, because the fate of our species depends on a scientifically robust solution to the contradictions we inherited.

The Trust Paradox is a challenge faced by all life, but answers to the question have varied depending on evolutionary pressures. Even within an individual species, the answers can change over time as it gains a foot-hold over its environment. Once our ancestors got the hang of survival and proliferated, their success, paradoxically, came back to haunt them. With so many people living in ever-expanding larger groups, how did we begin to scale trust to individuals who weren’t family? Humans innovated novel ways to solve this problem.

The next solution, after kin, was friendship. Rare in the animal kingdom, friendships worked keenly for humans living in face-to-face social worlds. Humans are not the only species with friendship, but it’s not typical in the animal world and the way human friendship is expressed is special. Friendship serves as our species’ crowning ethical achievement and has been suggested to be the origin point for the evolutionary emergence of morality.

As opined by Nicholas Christakis: “Our assembly into networks of friendships sets the stage for the emergence of moral sentiments. At their core, moral compunctions relate to how people interact with others, especially those who are not kin and for whom the bonds of kinship and the inexorable workings of inclusive fitness are not enough of a guide . . . friendship lays the foundation for morality.”

Perhaps the most noble and virtuous quality ever produced by natural selection is the transcendence of kin selection to a truly moral sensibility expressed by way of friendship. After all, friends don’t need to have sex with each other or share in childrearing in order to feel that they have a special relationship. This too was a novel, innovative answer to the question “In whom do you put your trust?”

All tribes are, in effect, a type of secret society.

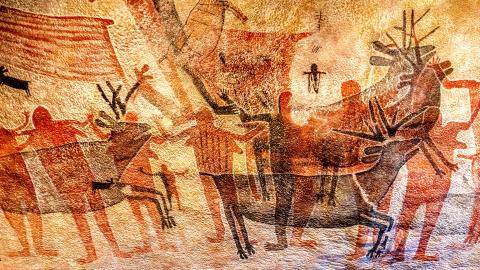

But at this point in the evolutionary story our ancestors were multiplying in droves. Friendship and kin selection gave us the new and unprecedented heroes of the Paleolithic, the avengers of kin and kith. Myths and legends remain of their exploits—a mother laying down her life for her daughter, a blood brother giving his life for a friend. These were all canonized in the stories that our ancestors passed down by word of mouth, which were later written down by scribes. But this success came with another round of costs incurred by increases to scale. We were so successful in reproducing that we became encroached by strangers. Humanity needed a new answer to the trust dilemma.

The answer was to become tribal.

As we explore the natural history of tribalism, we will see that some three hundred thousand years ago humans chanced upon a revolutionary adaptation that led to the encoding of the Tribe Drive in our DNA. This was the evolution of nested groups, each with their own particular symbols—and enshrined shared myths and values—that bound participants together in trusting relationships. All tribes are, in effect, a type of secret society, and the passwords to unlocking full rights and responsibilities of membership reside in the symbols used to verify that one is part of the tribe.

Religion is one such signal. The ancient Israelites recorded it in their sacred texts, in Psalms 16:1: “Preserve me, O God, for in You I put my trust.” The Mesopotamian goat herders of three thousand years ago were putting to scale the tribal solution our African ancestors had innovated three hundred thousand years beforehand. If we all believe in the same tribal God, we can trust each other even though we may have never before met. If your signal is not received as honest, you gain no entrance into the social inner sanctum. But if others recognize your signals as honest, you pass the test and are treated with a positive bias and, buttressed by your shared identity protective cognition, given tribal privileges.

Humanity had a new way to promote cooperation . . . but at a terrible, horrific cost. Once in-groups exist, by definition, so too do out-groups. It was both feature and bug, curse and blessing.