Cassowaries: Ancient humans may have reared deadly birds 18,000 years ago

- Native to Australia and New Guinea, cassowaries are considered one of the world’s deadliest birds.

- A recent analysis of ancient cassowary egg shells suggests that hunter-gatherers reared the giant birds as early as 18,000 years ago.

- The hunter-gatherers likely raised cassowaries — which imprint readily on humans — for their meat, bones, and feathers.

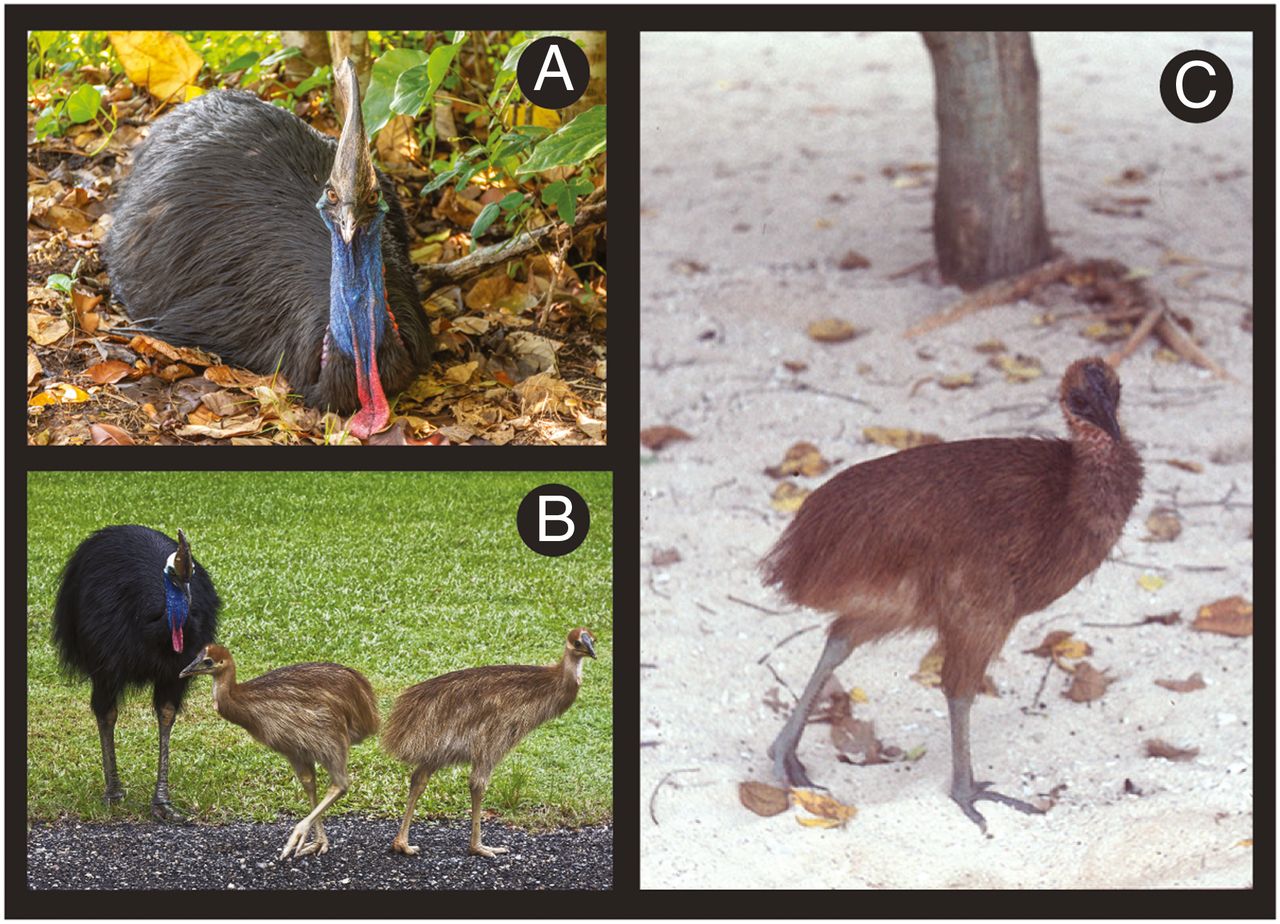

It is no wonder cassowaries are often called modern-day dinosaurs. Like some theropod dinosaurs, from which all birds descend, cassowaries sport a helmet-like structure, called a casque, atop their colorfully feathered heads. They can tower nearly six feet tall and weigh up to 167 pounds, outsizing all other modern birds besides emus and ostriches.

But it is the cassowary’s power and three sharp claws that most distinguish it from other modern birds. Cassowaries are one of a few birds known to have killed humans. With their powerful legs, which can propel them to speeds up to 30 mph, the birds can kick humans and other animals, slicing flesh in the process.

In his 1958 book Living Birds of the World, the ornithologist Ernest Thomas Gilliard wrote: “The inner or second of the three toes is fitted with a long, straight, murderous nail which can sever an arm or eviscerate an abdomen with ease. There are many records of natives being killed by this bird.”

So it may seem that the cassowary, territorial and potentially lethal, would be a poor choice of animal for ancient humans to rear. But a new study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggests that hunter-gatherers in the rainforests of eastern New Guinea did just that some 18,000 years ago. The findings mark what could be the earliest case of humans breeding birds, preceding the domestication of chickens by millennia.

Searching for clues in eggshells

The main goal of the recent study was to investigate whether early hunter-gatherers in the cloudy rainforests of New Guinea strategically collected and reared cassowaries. To find out, the researchers examined cassowary eggshells, which they described as an “understudied archaeological material with potential to clarify past interactions between humans and birds.”

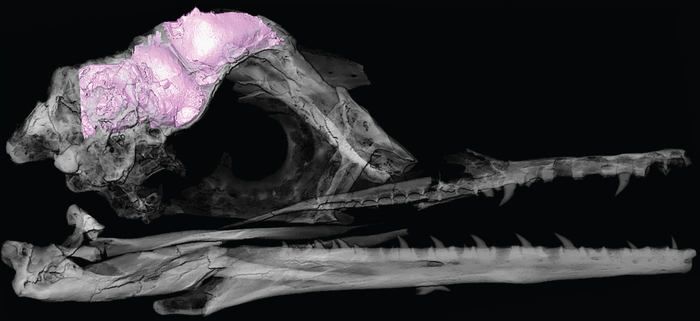

The characteristics of eggshells can offer clues as to when — in terms of embryonic development — the eggs hatched or were broken. To develop a model for analyzing avian eggshells, the team first examined shells from emus and ostriches, finding that they showed certain microstructural changes depending on the stage of development of the chicks inside.

By pinpointing the stage at which batches of eggs were broken, the researchers could make inferences as to why hunter-gatherers harvested cassowary eggs. For example, eggs harvested at the latest stages of development were likely used as food.

To examine ancient cassowary eggshells, the team used 3D laser microscopy to analyze more than 1,000 pieces of eggshells discovered in two rock shelters in New Guinea, where the cassowary is native, in addition to surrounding islands and Northern Australia.

The analyses of the eggshells in New Guinea showed that most of the eggs were harvested at later stages of development, suggesting that hunter-gatherers “preferred consuming eggs with fully formed embryos — considered a delicacy in some parts of the world,” the researchers wrote. Burn marks on the eggs supported this hypothesis. The marks “could indicate that early stage eggs that contained primarily liquid contents (yolk and albumin) were preferentially cooked intact over an open fire or in an earth oven.”

The first birds raised by humans

But the team also noted the possibility that early hunter-gatherers were letting the eggs hatch in order to rear cassowaries. After all, cassowaries are meaty birds that would have provided a substantial amount of protein to supplement hunter-gatherers’ plant-rich diets, while the birds’ feathers and bones were likely prized possessions, as they are today in New Guinea. And even though cassowaries are dangerous and territorial, cassowary chicks readily imprint on humans when raised from birth, meaning it would not have been too dangerous for hunter-gatherers to raise the birds into adulthood.

Still, the researchers are not sure exactly how the hunter-gatherers went about collecting the eggs. The researchers noted that cassowary nests are typically hard to find. What’s more, male cassowaries, who watch over the nests almost nonstop until the eggs hatch, have been known to become violently territorial when approached by humans and other animals. Hunter-gatherers might have sometimes opted to hunt the male and then collect the eggs. Overall, the researchers proposed that “cassowary egg harvesting may have been more common than the harvesting of adults.”

The researchers concluded by noting that the methods they developed to study human-cassowary interactions in New Guinea “has great potential to elucidate human interactions with avian species globally and may greatly expand our understanding of the decline and extinction of many large flightless birds following human colonization of new regions.”