People in 1920s Berlin nightclubs flirted via pneumatic tubes

You hear it often: dating today doesn’t work like it used to. Or: apps like Tinder have made flirting more distant.

But the process of staring, judging, and messaging potential suitors from afar—hallmarks of modern dating apps—is not new. Beginning in the 1920s, nightclub-goers in Berlin who feared face-to-face encounters could communicate with beautiful strangers from across the room.

All they needed to do? Turn to the nearest pneumatic tube.

Two nightclubs in particular—the Resi and the Femina—pioneered the trend. At the Resi (also called the Residenz-Casino), a large nightclub with a live band and a dance floor that held 1,000 people, an elaborate system of table phones and pneumatic tubes allowed for anonymous, late-night flirtation between complete strangers.

A Chicago Tribune article describes the Resi’s “nightly ‘spectacular’—‘a dancing water ballet’ with jets of water rising and falling to a recorded symphony while colored lights flash.” The water-jet ballet, now known as a “Waltzing Water,” began in 1928 and drew in many visitors.

But the Tribune article refers to the system of phones and pneumatic tubes at each table as the Resi’s “big lure.”

Phones were fixed to individual tables, and above many was a lighted number. Singles needed only to look around the room until a fetching stranger caught their eye, note the number, and then direct a message to that table. “Lonesome Americans, and others, can call or send a note to equally lonesome women who look like they would enjoy company,” the article noted.

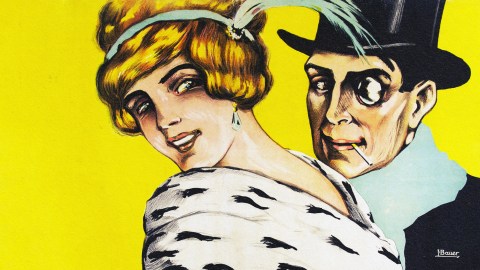

In 1931, during the heyday of this across-the-nightclub flirtation, The Berliner Herolddescribed the process of receiving a call from an amorous stranger: “the tabletop telephones buzzed, and the acquaintance with the blonde, raven-haired or redheaded, monocle-wearing beauty was made, one was no longer alone, and had twice as much fun.” (At the Ballhaus Berlin, this numbered phone system still lives today—check out photos here.)

Similar systems thrived at the Femina, the larger of the two nightclubs, which boasted more than 2,000 seats, “two large bars and a smaller one in the vestibule, in addition to three orchestras, a hydraulic dance floor,” and over 225 table telephones, which were accompanied by instructions in both German and English.

But for those who were too shy to pick up the phone, the pneumatic tubes offered a perfect alternative. The tubes were built into the handrails, and one was located at each table. The nightclub provided paper on which to scrawl notes. Patrons only had to specify where they wanted their missives sent. Like messaging on a dating app, but with—you know—tubes.

At the Resi, many provocative notes were passed around, but eager flirters needed to be careful—“messages sent by tube [were] checked by female ‘censors’ in the switchboard room” in an early form of comment moderation.

The pneumatic tube system existed for decades, and Americans who visited Berlin after World War II remember it fondly.

Today, many fictionalized accounts memorialize it: Then We Take Berlin by John Lawton describes how visitors could “write a message, stick it in the snake’s head, yank on the handle and the pneumatic tube would whisk it up to the top gallery and they’d redirect it to the right table.” (Cabaret, meanwhile, tributes the table phone system in “The Telephone Song.”) Ian McEwan’s novel The Innocent also offers an evocative tribute. When his main character, Leonard, visits a fictionalized version of the Resi nightclub, the protagonist finds a pamphlet that boasts the establishment’s “Modern Table-Phone-System” and “Pneumatic-Table-Mail-Service,” which sends “every night thousands of letters or little presents from one visitor to another.”

This “table mail service” was real, and allowed patrons to send more than just a handwritten note to that handsome stranger across the way. The Resi offered a long menu of gifts that visitors could dispatch via pneumatic tube—including perfume bottles, cigar cutters, travel plans, and, according to one source, cocaine.

This article originally appeared on Atlas Obscura, the definitive guide to the world’s hidden wonder. Sign up for Atlas Obscura’s newsletter.