4 reasons why you should read old, classic books

- It can be difficult to find the time and determination to read old books.

- But old books are uniquely valuable in helping us better understand ourselves and the modern world.

- To read more old books, don’t treat them as an obligation. Wait until a specific classic or author calls you.

Imagine you’re looking for your next book. You peruse your bookshelves, registering the unread titles as you go. Among them are several older books, and you feel a familiar pang of guilt over those classics you always meant to read but haven’t. Is today the day you finally pick one off the shelf? It’s a common reader’s dilemma, but more often than not, you opt for a newer book that feels more relevant to your interests and the world around you.

That makes sense. It’s understandable that you would want to explore today’s pressing issues, keep your knowledge up-to-date, and support the living writers whose works you enjoy — all of which demand reading modern books. And with so many books being published every year, it can be challenging to find the time — to say nothing of the determination — to revisit the classics gathering dust on your shelves.

I get that, yet I still want to make the case that reading older books, particularly those laureled as the classics, is a valuable practice that we should make more time for. These works are often not only wonderful reads in their own right but also provide unique privileges to contemporary readers that newer books simply cannot.

#1. Read old books to better understand people

One barrier to reading older books is the thought that such works are obsolete. To live your life, you don’t need to understand the intricacies of medieval Chinese warfare, the struggles of the Victorian working class, or the myths of people who honestly thought a giant serpent enveloped the world. But the truth is that older books can still offer us valuable insights into the universal qualities that make us human.

Although our beliefs and collective knowledge have certainly changed, the fundamental struggles we face, the questions we ask, and the values we hold are all reflected in the writings of authors from past generations. Aristotle, Spinoza, and Descartes puzzled over problems that still perplex philosophers. Thomas Paine and Karl Marx continue to shape how we view politics, social organization, and human rights. And while most of us don’t believe our fates are written in the stars, we still look to the skies for answers to nature’s great mysteries.

In literature, the stories and themes that captivated readers centuries ago continue to resonate. The pride of Odysseus, the passion of Shakespeare’s characters, and the existential dread of Ivan Ilyich remain inextinguishable characteristics of our inner lives.

Reading older books allows us to engage in this historic cosmopolitanism, exploring our shared humanity not just across culture but also across time.

Of course, you’ll read about ideas and traditions that are obsolete — even ignorant and offensive. That’s fine, even preferable. As the critic Michael Dirda writes for the Washington Post, read them anyway. He points out that recognizing mistakes, prejudice, and inhumane practices isn’t the same as condoning them.

“What matters is acquiring knowledge, broadening mental horizons, viewing the world through eyes other than your own,” Dirda writes. “The great books are great because they speak to us, generation after generation. They are things of beauty, joys forever.”

#2. Read old books to reassess the modern world

Even with that mindset, we may still find the ideas of old books to be silly, bigoted, or simply wrongheaded. However, it’s important to remember that the authors of these books were shaped by their time, culture, and the collective knowledge of their era. They were unable to see their biases and assumptions, which are now clear to us thanks to the distance of history.

At the same time, we should also recognize that we are not immune to biases and assumptions ourselves. These still cloud our ability to solve complex problems, engage in meaningful debates, and unravel the mysteries that seem intractable to us. In fact, future generations will look back at our books with the same sense of incredulity.

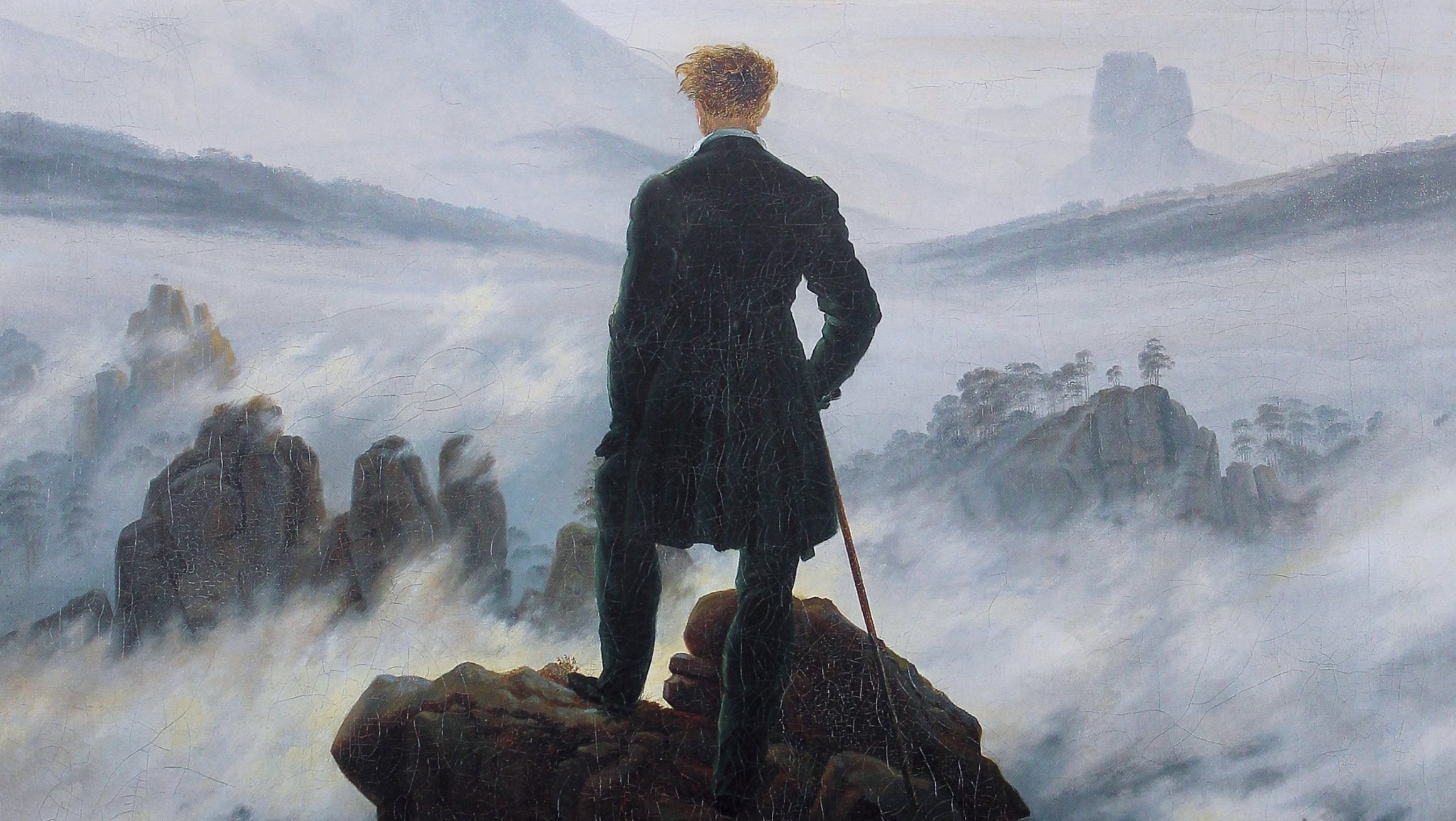

Old books can help us guard against these limitations by immersing ourselves in the cultures and ideas of earlier eras. Jeffery Brenzel, dean of undergraduate admissions at Yale University and a lecturer in the university’s philosophy department, calls this the “value of strangeness.” He likens reading old books to traveling abroad. After experiencing another culture, many travelers return home and see their own differently. They open their mind to the assumptions they held and learn to reconsider those assumptions more thoroughly. Old books offer us this kind of mental travel.

C.S. Lewis made a similar point in his introduction to Athanasius’ On the Incarnation:

“People were no cleverer then than they are now; they made as many mistakes as we. But not the same mistakes. They will not flatter us in the errors we are already committing; and their own errors, being now open and palpable, will not endanger us.”

He continues:

“Two heads are better than one, not because either is infallible, but because they are unlikely to go wrong in the same direction. To be sure, the books of the future would be just as good a corrective as the books of the past, but unfortunately we cannot get at them.”

#3. Read old books to join great conversations

Lewis adds that only reading modern books is like trying to join a conversation halfway through. Yes, you can jump in and may do a passable job engaging. However, you will have a much better command if you join the conversation from the beginning. Older books preserve these conversational threads so we can do just that.

This is essentially what the philosopher Alfred North Whitehead had in mind when he wrote: “The safest general characterization of European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato.” Brenzel puts it a little more straightforward:

“You simply cannot study the history of Western thought without running into Plato and Socrates around every corner. You can’t read a thinker who hasn’t been influenced by these ideas in some way as well as the way that they actually posed the original questions.”

As an example, Brenzel asks us to look at Christianity, a religion at the heart of many modern conversations and debates. Many assume that Christian views come straight from the Bible, but they evolved from an intellectual tradition that spanned centuries and is as much Greco-Roman as it is Gospel.

The Apostle Paul’s views were heavily influenced as much by the Greek traditions of Plato and Aristotle. Paul and Plato would both prove an indelible influence on St. Augustine. Augustine’s views would go on to influence Thomas Aquinas, who would then influence Dante Alighieri, who would influence John Milton, who would influence how other writers read and interpreted the Bible for centuries. Today, Christian views on everything from Satan, to the afterlife, to the cosmic struggles of good and evil would be completely foreign to 1st-century Christians, and that’s because of how the intervening “conversations” changed those views over time.

And similar conversations have taken place in intellectual traditions all over the world, from Middle Eastern poetry to the Vedic traditions to the Tao Te Ching.

#4. Read old books because they call to you

The previous reasons are ultimately meaningless if we don’t find reading old books gratifying. Otherwise, why bother taking one off the shelf? Thankfully, old books can be fun. They can also be inspiring, terrifying, rewarding, challenging, exhilarating, and provocative. They can instill in us not only knowledge and wisdom but the full range of human emotions. But none of that is possible if we approach them as the mental equivalent of dusting the house.

For the record: This isn’t a new phenomenon bred in a focus-deprived generation raised on TikTok and two-day shipping. As Mark Twain once quipped: “A classic is something that everybody wants to have read and nobody wants to read.” A sad irony then that his many fantastic books now exist on many people’s literary chore lists.

To overhaul this mindset, don’t approach older books the way we did in school. These aren’t burdens you need to bear to become educated or cultured or pass some hidden life exam. There is no grade to be had. Instead, wait until a particular classic calls to you. If you’re not ready for the philosophies of Plato, try the plays of William Shakespeare or the Romantic poetry of John Keats. If neither of those speaks to you, the Victorian era has some fantastic mysteries and ghost stories to get lost in (both favorites of mine).

Humanity’s collective library is vast, more than anyone can read in a lifetime. You’ll find something if you look.

What’s old is new again

Returning to our thought experiment above, it is counterproductive to feel guilty when you pass over older books in favor of something more recent. Those current events, pressing issues, and living artists need our attention, too. A good rule of thumb, one I borrowed from Lewis, is to make every third or fifth read a classic or much older book.

And don’t feel rushed either. Author Italo Calvino once defined the classics as:

“those books which constitute a treasured experience for those who have read and loved them; they remain just as rich an experience for those who reserve the chance to read them for when they are in the best condition to enjoy them.”

These works have waited a long time, in some cases centuries, to reach your bookshelf. What’s a few more years of waiting? Just as long as we give them the chance and are receptive when that time finally arrives to take them off the shelf.

Learn more on Big Think+

With a diverse library of lessons from the world’s biggest thinkers, Big Think+ helps businesses get smarter, faster. To access Big Think+ for your organization, request a demo.