Plato’s “Republic” was a totalitarian nightmare, not a utopia

- Plato’s Republic was the first utopian novel, complete with an ideal city: the Kallipolis.

- The totalitarian leanings of the Kallipolis have led many thinkers to criticize Plato’s vision of utopia.

- Plato’s Republic contains ideas that many modern readers will find repulsive — and figuring out why those ideas seem so ugly to us is a useful exercise.

Literature and philosophy are littered with visions of utopia drawn up by thinkers with various ideological frameworks. Some are based on alternative economic systems; some fit a specific view of human psychology; others hope to find harmony with nature. Like nearly every other area of intellectual endeavor, they all owe a debt to Plato, who did it first.

Plato’s Republic contains the first known sketch for a Utopian society. Part allegory, part legitimate policy proposal, and part critique of existing systems, the book offers many ideas that, allegedly, point to an ideal city.

Unfortunately, as we’ll soon see, nobody in their right mind would ever want to live there.

The first utopia

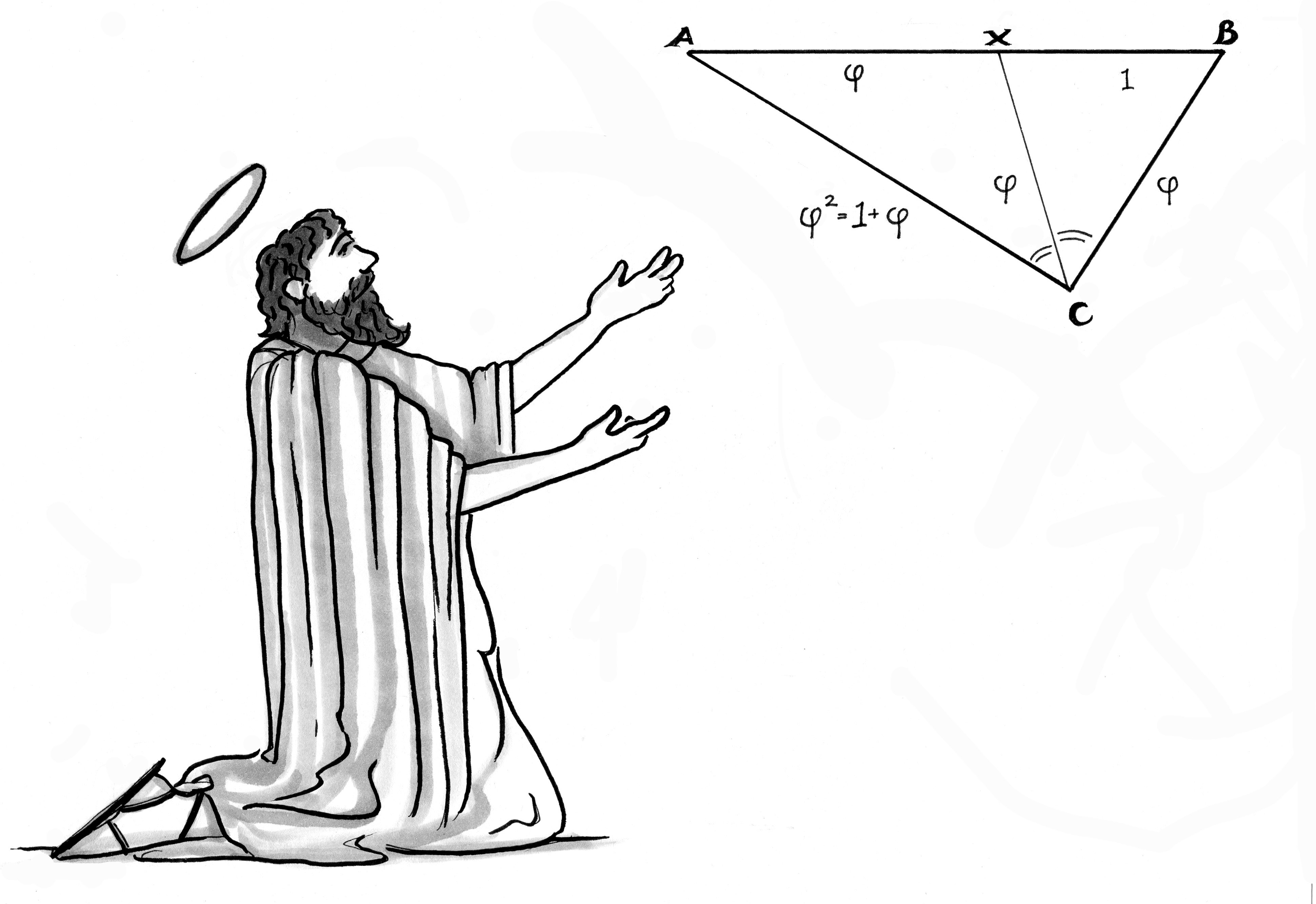

Most utopian literature begins by trying to answer the “what is the ideal society?” question. Plato’s Republic begins by trying to answer the question: “What is justice and is it good for a person to be just?” This is a very big question, and Plato answers it through analogy via his main character Socrates. He suggests that justice in the ideal city is akin to justice in a person, and that by understanding justice on the large, easy-to-see scale, we can understand it in the smaller.

The city, dubbed the Kallipolis, would be governed by philosopher-kings. Selected for their wisdom, these rulers would be educated for 50 years before taking control of the city. Guided by their understanding of the good, the just, and how to achieve it, they would drive the city toward peace and prosperity.

Men and women would be treated equally, as Plato can find no reason why either sex is fundamentally unable to do what the other can within reasonable limits. All children would be given a quality education suitable to their natural talents. All of this would be geared toward creating the best city possible, with high overall happiness, virtue, and harmony — at least as Plato conceived it.

The city would achieve this through an increasingly totalitarian series of laws and regulations that keep it functioning with little regard for the stated desires of the populace. While many of the specifics are left unstated, what is said is plenty.

The city features a rigidly enforced caste system with no social movement possible for adults. However, their children may be promoted or demoted based on how they do in school. The guardian and warrior class that rules and defends the city would be without personal and private property, living in communal abodes funded by taxes collected from the lower classes. All the rulers would be chosen from this class.

Speaking of children, families would no longer exist as single units. Instead, children produced by state-sanctioned marriages will be reared by the state. Alongside this would be a eugenics system featuring the infanticide of the children of “inferior parents” or any “defective” babies. Rigged lotteries would be used to assure that lower-quality parents don’t contaminate the bloodlines of higher quality stock.

To assure that the truth is respected, all the poets would be sent into exile. All works of culture, from plays to bedtime stories, would be approved by the rulers. Naturally, these rulers are the only people capable of grasping “truth” rather than cheap imitations of it.

The system would endure thanks to a “noble lie,” assuring the common people that souls come in varieties. The philosopher-kings have golden souls, their aids and warriors have silver ones, and the farmers, laborers, and craftsman are metaphysically made of brass and iron. The lie includes the warning that everything would fall apart if people of the wrong build are put in charge.

Oh, and it is doomed to eventual failure as Plato suggests all political regimes are. Sounds pleasant, doesn’t it?

The philosopher Karl Popper, whose objections to totalitarianism have appeared in several books, thought the ideas in Plato’s Republic were taken too seriously. With its dedication to the idea that social-engineering is not only possible but often desirable, and that all is permitted so long as the polity is being driven toward the “objective” good, Popper suggests that Republic intellectually inspired the totalitarian movements of the 20th century.

Allegedly, Ayatollah Khomeini, the founder of the Islamic Republic of Iran and leader of the Iranian Revolution, was inspired by the book when crafting the Iranian government, complete with its own philosopher-king. How well this worked out is subject to debate.

The philosopher Bertrand Russell, another critic of the book, argued that it was intended to be taken seriously as a society that could be enacted in ancient Greece, a point supported by a variety of evidence.

Any idea of utopia — modern or ancient — is going to be based on assumptions about people, societies, justice, and other concepts that someone else will find controversial. In the 2,000 years since Plato wrote his down, everything he said has gone from being deemed correct to being dismissed as nonsense. As a result, his perfect city seems monstrous to us today.

However, the discussion prompted by the debate over whether Plato’s Kallipolis is ideal, practical, or even possible has advanced our understanding of ethics and political philosophy. After all, we must ask ourselves why we like concepts like freedom and democracy when faced with an alternative that, allegedly, offers a better society.

As always, we might owe Plato a debt of thanks, even if we reject his philosophy wholesale.

This article was originally published on November 5, 2020. It was updated in September 2022.