Bionics center at MIT may usher in our cyborg future

- Bionics replace or restore the function of missing or damaged body parts with electronic devices.

- Philanthropist Lisa Yang has gifted MIT $24 million to further the field of bionics through a dedicated research center.

- One of its major projects is a “digital nervous system.”

This article was originally published on our sister site, Freethink.

A new MIT research center promises to accelerate our journey to a future in which bionics help people everywhere overcome the challenges of disabilities — and even enhance human potential.

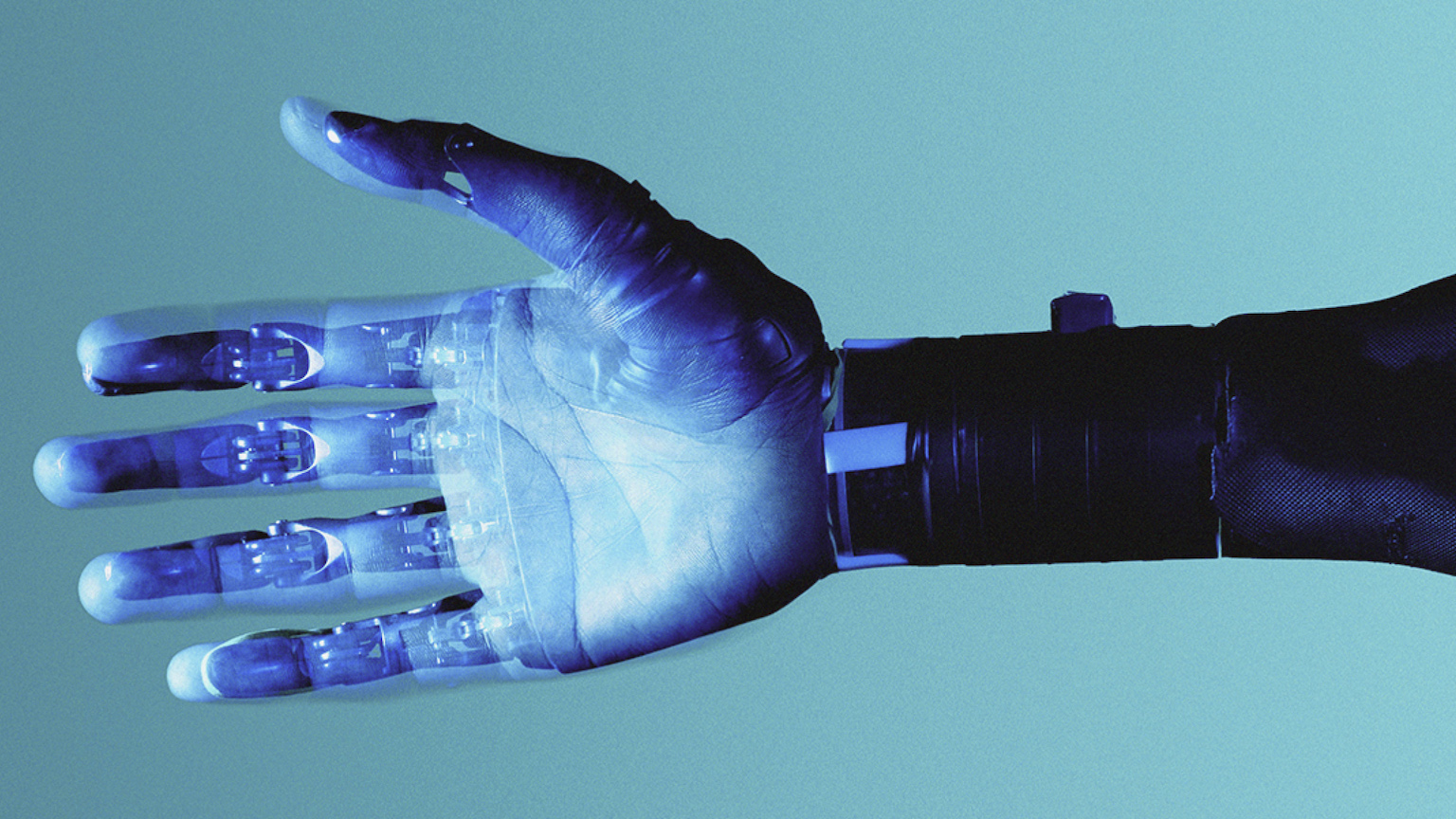

The future is near: Bionics replace or restore the function of missing or damaged body parts with electronic devices — examples include leg exoskeletons and mind-controlled prosthetic arms.

These devices can be life-changing, but many are still unique and experimental, meaning the only people to benefit from them are a handful of study participants. The faster we can advance bionics research, the sooner they’ll be available to everyone who needs them.

“We must continually strive towards a technological future in which disability is no longer a common life experience,” MIT professor Hugh Herr, himself a double amputee, told MIT News.

MIT’s bionics center: Now, philanthropist Lisa Yang has gifted MIT, one of the world’s most elite science and tech universities, $24 million to further the field of bionics through a dedicated research center, co-led by Herr and MIT professor Ed Boyden.

“The K. Lisa Yang Center for Bionics will provide a dynamic hub for scientists, engineers, and designers across MIT to work together on revolutionary answers to the challenges of disability,” MIT President L. Rafael Reif said.

“With this visionary gift, Lisa Yang is unleashing a powerful collaborative strategy that will have broad impact across a large spectrum of human conditions,” he continued, “and she is sending a bright signal to the world that the lives of individuals who experience disability matter deeply.”

Bionics you can feel: The center will focus on developing three specific bionics technologies during its first four years.

“We must continually strive towards a technological future in which disability is no longer a common life experience.”

HUGH HERR

One is a “digital nervous system” that will help people overcome movement disorders caused by injuries to their spinal cord — it’ll do this by activating the muscles that control their limbs, while also working to repair their spinal injuries.

Mind-controlled exoskeletons to help stroke survivors and people with musculoskeletal disorders move their limbs are another research focus, and the third is the development of more intuitive bionic limbs that include sensations of touch and position awareness.

From lab to home: In addition to pushing bionics to new limits, the center will also develop a mobile delivery clinic that can meet a person in need of a prosthetic at their home, collect medical images from them, design and build their personalized limb, and then fit them for it.

This clinic will be field tested in Sierra Leone, where less than 10% of the thousands of people with amputations have a functional prosthesis.

“I am proud that Sierra Leone will be the first site for deploying this state-of-the-art digital design and fabrication process,” President Julius Maada Bio said.

“I am overjoyed that this pilot project will give Sierra Leoneans (especially in rural areas) access to quality limb prostheses and thus improve their quality of life,” he added.