The Gray Lady’s Shady Ethics

With the newspaper industry in turmoil and media suffering from what Clay Shirky refers to as “mass amateurization,” it’s not a particularly good time to entangle the New York Times in an ethics scandals, but I guess these things are difficult to plan.

Last week, Maureen Dowd made headlines for something other than her profoundly irritating op-eds when she was accused of plagiarizing Talking Points Memo‘s Josh Marshall. To clarify, here’s Dowd’s passage, which ran on May 17th:

“More and more the timeline is raising the question of why, if the torture was to prevent terrorist attacks, it seemed to happen mainly during the period when the Bush crowd was looking for what was essentially political information to justify the invasion of Iraq.”

And Marshall’s, which was posted the previous Thursday:

“More and more the timeline is raising the question of why, if the torture was to prevent terrorist attacks, it seemed to happen mainly during the period when we were looking

for what was essentially political information to justify the invasion

of Iraq.”

(Note the difference, which replaces

the phrase “the Bush crowd was” with Marshall’s more inclusive

“we were”). When confronted with accusations of plagiarism,

Dowd confessed to having lifting a sentence from a friend’s email (who

failed to mention she had borrowed liberally from Marshall’s article)

and stood her ground, refusing to acknowledge deliberate misconduct.

Personally, I fail to understand how

repeating a friend’s words without crediting her doesn’t constitute

plagiarism in itself, but that’s not really the issue here.

In response, Times public editor

Clark Hoyt ran a

roundup of two more scandals that have marred the

paper’s name in recent weeks: Thomas Friedman’s decision to accept a

$75,000 speaking gig at a government agency in Oakland, and more spectacularly,

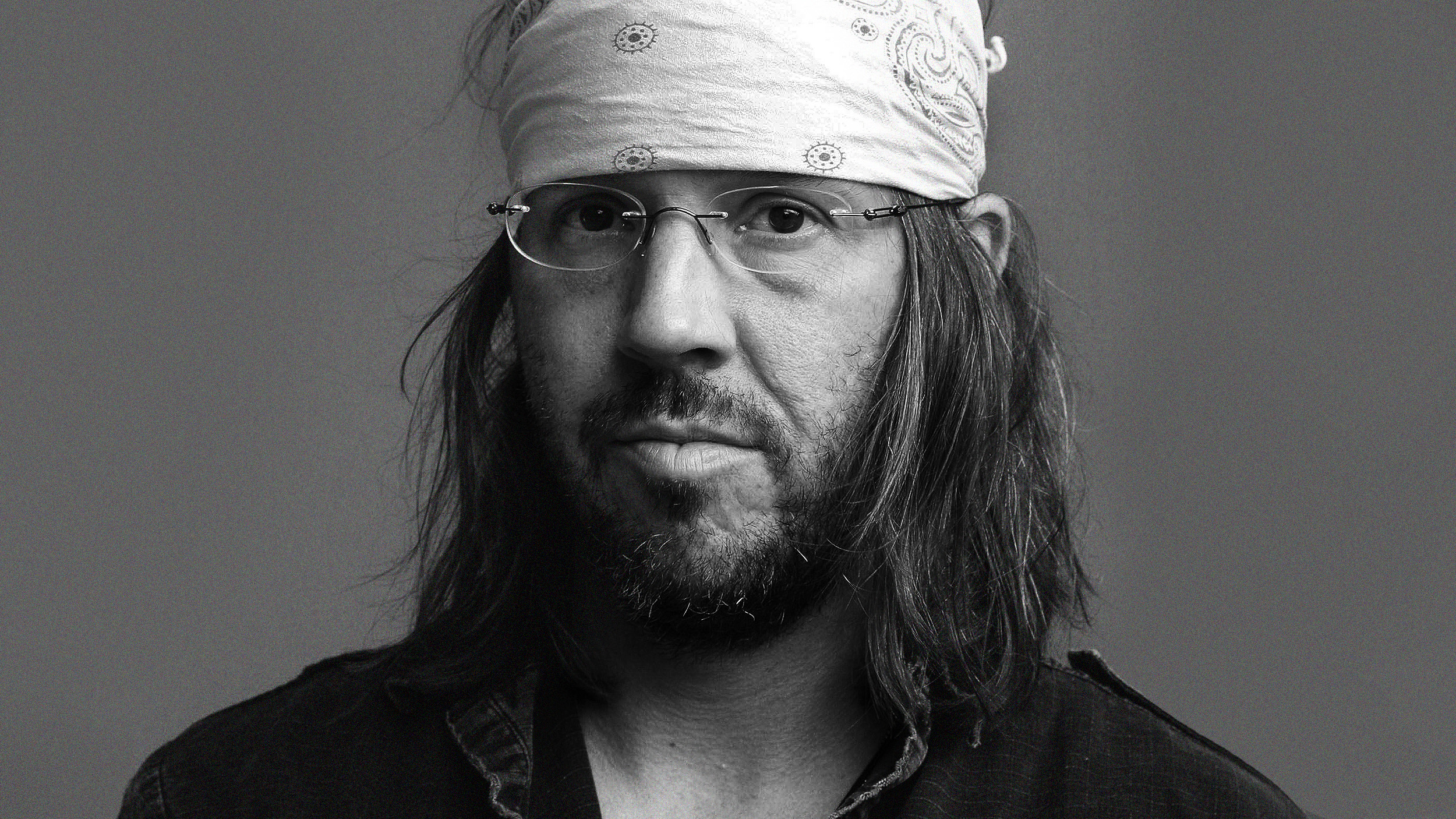

the downfall of gonzo economic journalist

Andrews

, who drove himself

into financial ruin while researching the ways in which people fall

into debt. According to Hoyt, Andrews is “seven months behind on

his mortgage, he may lose his home unless

‘Busted,’ which comes out this week, is a hit.”

I’m sure there are a number of poets and novelists who can commiserate,

but as a financial reporter, this is particularly scandalous.

Of course, mistakes are unavoidable,

and in the cases of Dowd and Friedman, theirs were understandable if

not stupid. As the exemplar of print journalism, however, the thin line

delineating the Times from the wilds of the internet is not only

the quality of its writing, but also the standards of its ethics. Scandals

such as these put the paper in the precarious position of leaving quality

control to its readers, and, in the minds of its critics, demonstrating

the merits of open-source editing. When Dowd’s column ran, the sentence

was first caught by a blogger at TPMcafe who then turned the story into

national news. At the Huffington Post, John Ridley wrote an

op-ed trenchantly titled “The New York Times:

Let It Fall,” and in The Guardian‘s “Comment is Free”

section, Dan Kennedy took the opportunity to

rack up a list of the Times’ more glaring ethical failures.

But in spite of all this, these scandals

could be the best thing that’s happened to the paper in recent memory.

As a famously cloistered institution,

the Times is increasingly compromised as news becomes a tool

of the masses. With troops of citizen journalists pounding at the gates,

the paper of record has conceded by opening itself up a little — most

notably through its hyperlocal blogs — and introducing a little more

transparency to traditional journalism. This, of course, is not a replacement

for hard reportage, and moreover, has had the unfortunate effect of

shifting coverage away from real news and more towards lifestyle pieces

and fluff content. (If you don’t believe me, see

this). However, with the recent wave of scandals,

one important thing has happened: the Times has stepped up and

revealed some of the machinations behind running the most respected

paper in the world.

In Hoyt’s article, the public editor

elucidates the logic underpinning journalistic ethics, going through

the ways in which the Times’ ethics police keep writers from

slipping on research or racking up millions on the lecture circuit.

With all the talk lately of the Death of Journalism, ethics is something

that has gone largely under the radar. While open-source peer-editing

may keep information largely accurate, it doesn’t promote a culture

of integrity and newsworthiness like an established paper does. Rather,

that’s the job of the individual publication, or in the case of the

Times

, the teams of editors and advisors kept on staff precisely

to counterbalance the work of the writers. While the ethics editors

have been called into the limelight for the wrong reasons — although,

like fact-checkers, I can’t think of any other way they’d get public

attention — the scandals also highlight the significance of their work,

and the thought that goes into maintaining the integrity of the paper.

Perhaps rather than see these scandals as an omen for print media, it’s

more useful to learn from what they expose about our expectations for

good journalism.