Small, ultra-powerful fusion energy? MIT is closer to it than ever.

For human beings, fusion energy has pretty much been reserved for the Sun and other stars to function and to make hydrogen bombs.

Now, Massachusetts Institute of Technology is on the edge of using it for almost unlimited power.

Commonwealth Fusion Systems has donated $50 million to MIT to help fund the effort. It’s a welcome injection of resources; the United States Department of Energy has helped fund the study of this effort for decades, but that was cut off under the current administration.

While fission produces radioactive “waste” as a result of its atom smashing, fusion produces helium and an almost inconceivable amount of energy.

To give you an idea of how much energy we’re taking about? A single atom of a form of hydrogen called in deuterium, found in sea water, has more than 2 million times the power of a molecule of natural gas.

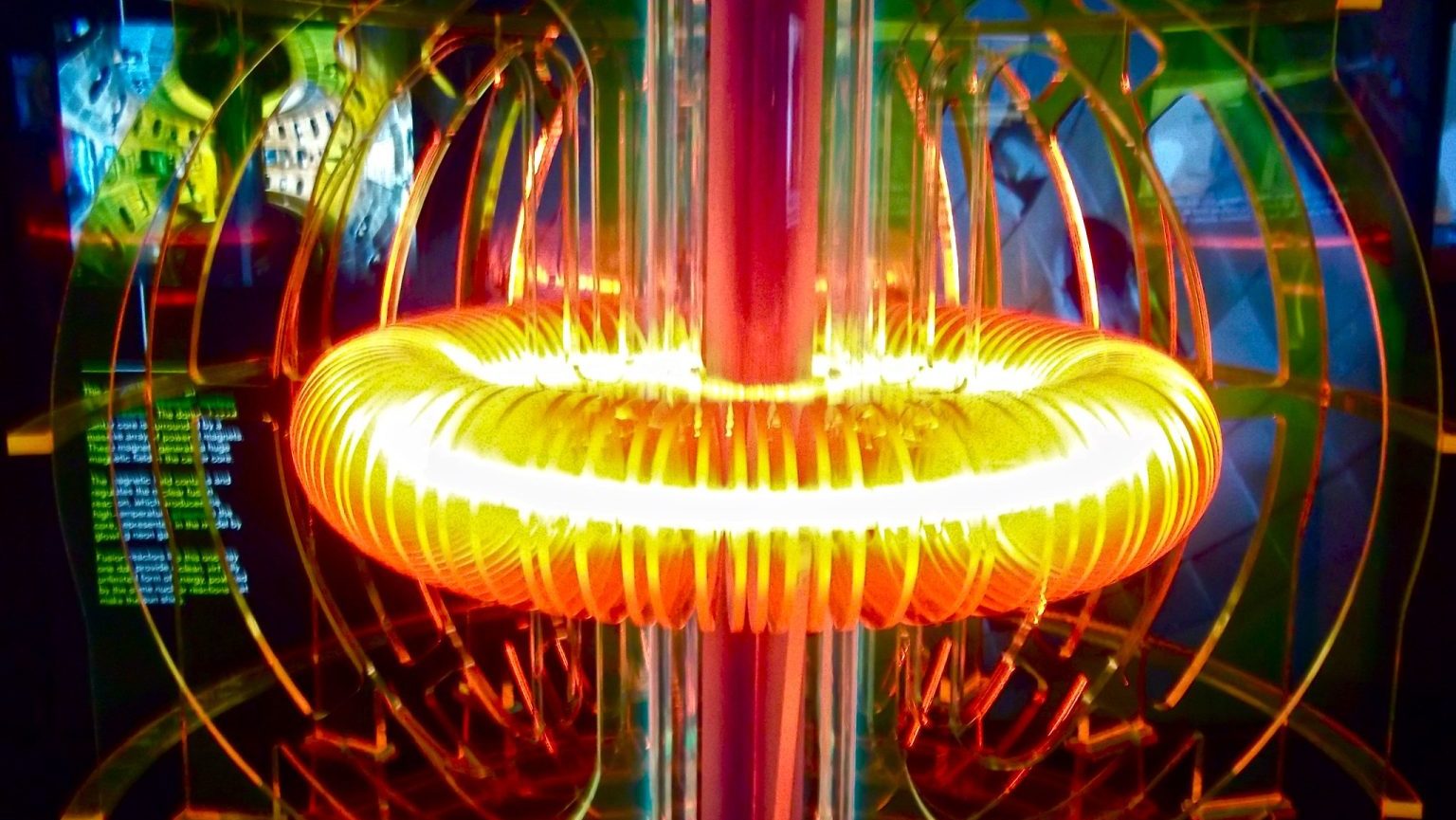

The hitch until now has been in controlling the hydrogen reaction — because without confining it, and controlling it, you have a bomb. Basically.

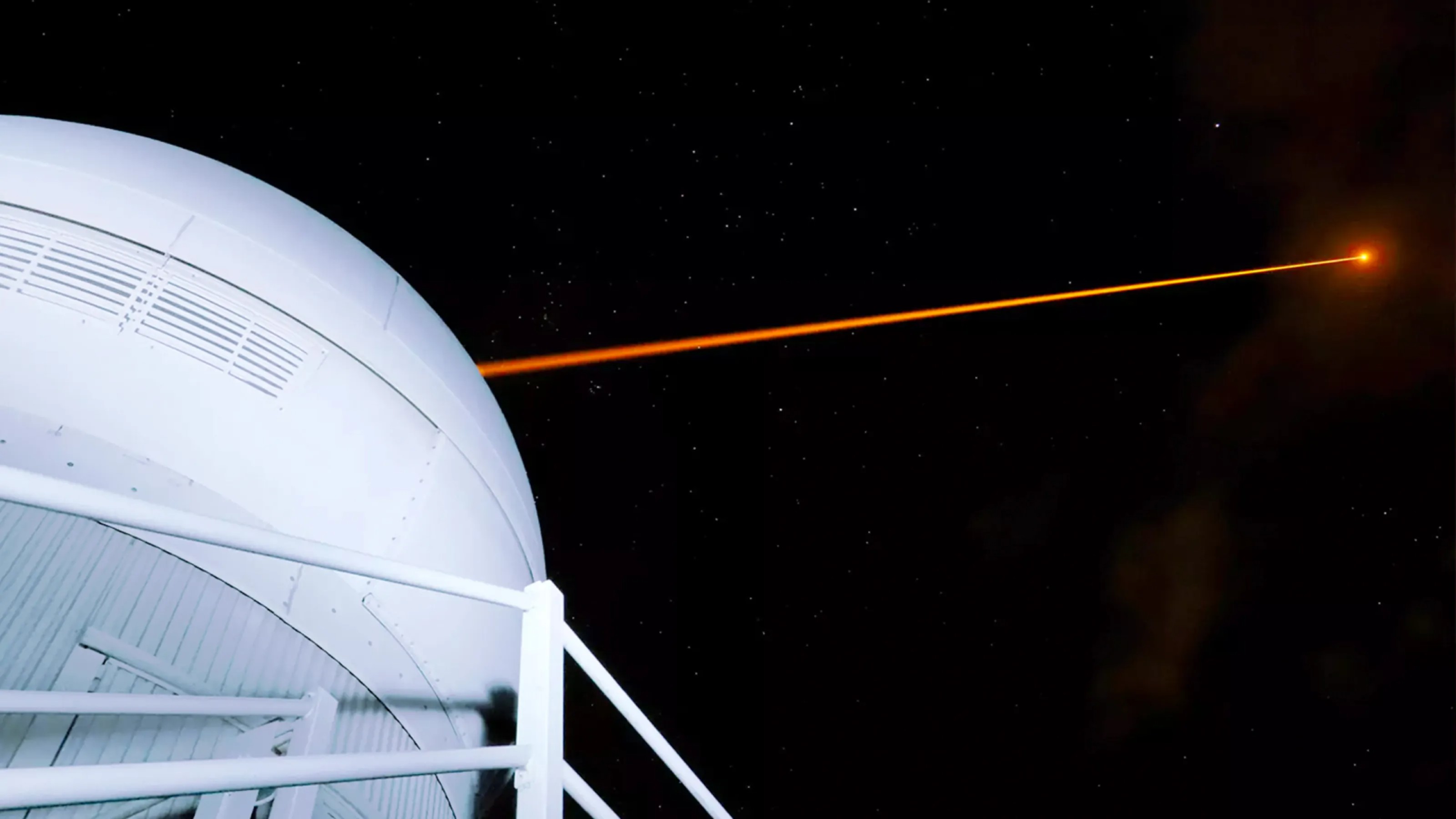

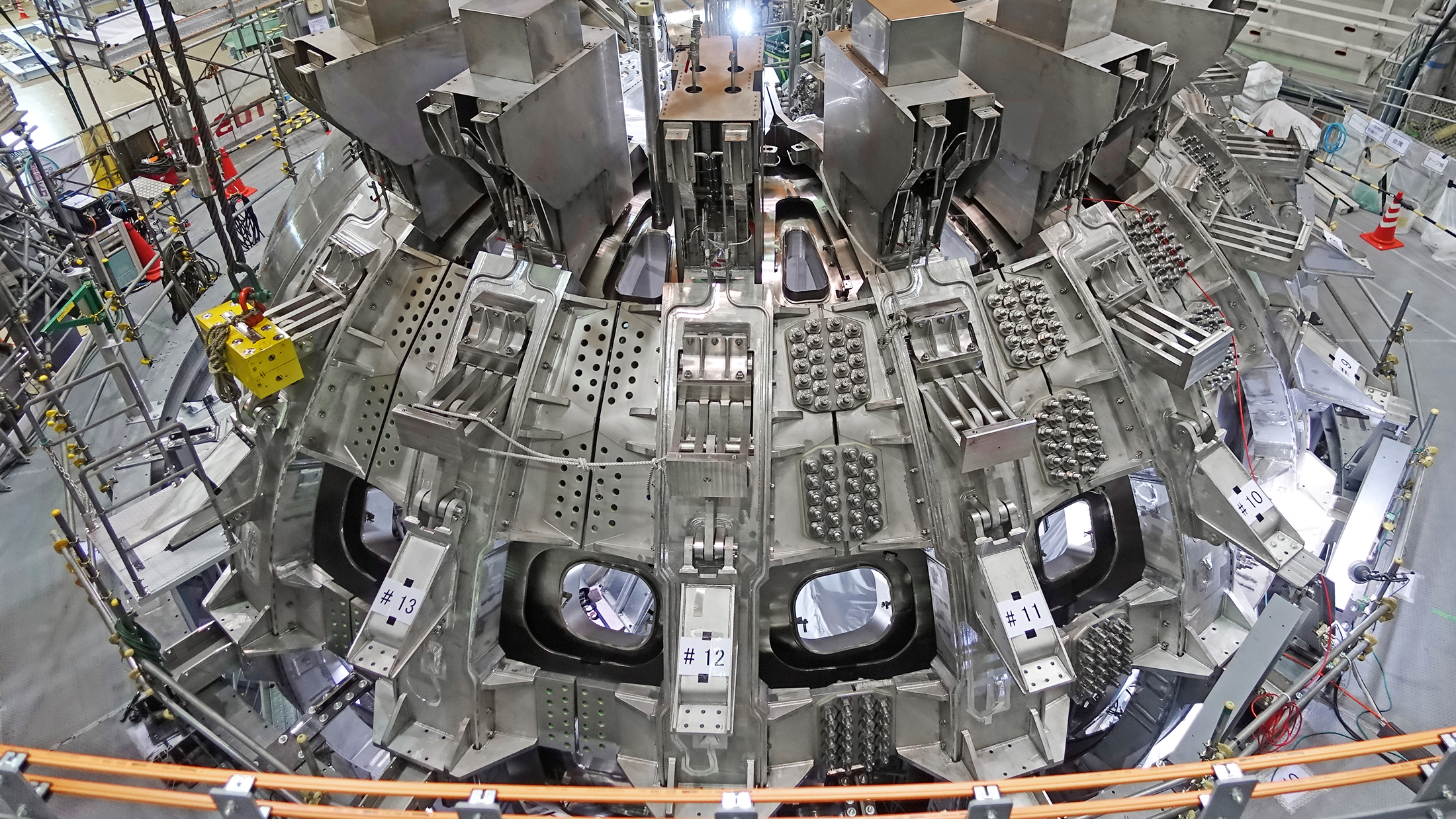

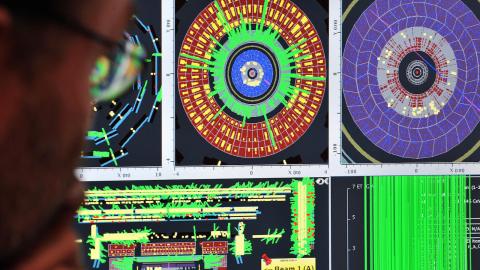

They will use ultra powerful electromagnets to control the reaction and force the nuclei to fuse together. They have been using powerful copper magnets so far, and replacing those is the key to making this work. The other goal is to make the reactors quite small, which the electromagnets will allow — about 20 feet in diameter is the goal.

They aim to get a test reactor, named SPARC, up and running within 10 to 15 years.

Mind you, this entire concept has been kicked around in the scientific community and even at the government level for 40 years; however, this appears to be the first time it actually could work.

“If we succeed, the world’s energy systems will be transformed,” said Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor Maria Zuber. “An entirely new industry may be seeded potentially with New England as its hub.”