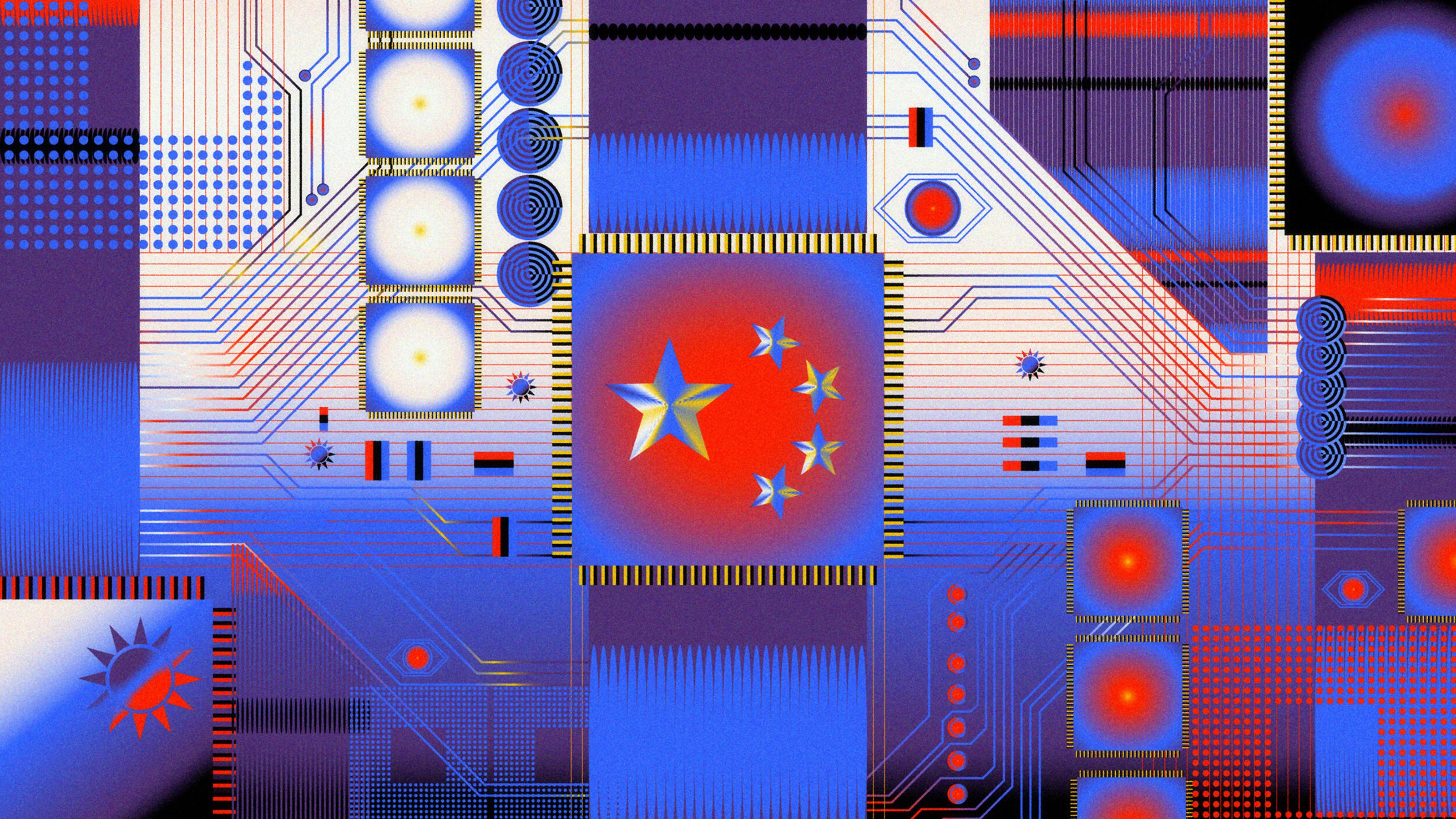

Google and the Red Dragon

After travelling through China with a local guide who was quite independent and critically minded, reports on the country from reputed American sources like the New York Times began to frustrate me. In one way or another, most articles would accuse Chinese authorities of using propaganda to (mis)inform their citizens about political issues. Now, since Google disclosed that the gmail accounts of several human rights activists were targeted by hackers from within China, the Red Dragon is back, but how dangerous is it really?

“The mountains are high and the Emperor is far away,” the Chinese proverb goes. While, for example, China’s one-child policy is an easy target for those aiming to criticize authoritarian Chinese rule, it is not uncommon for Chinese families to have more than one child. After all, it takes more than one offspring to continue the family farm or business. Besides, the population in China is growing, not decreasing by half every new generation!

Very ironically, reports from American news companies that criticize Chinese misinformation seem colored by the lens of U.S. foreign policy, a policy which seeks to isolate the world’s rising power.

So, while Google began censoring itself in China in 2006, i.e. preventing information about human rights violations from reaching the public, its conscience is no longer so clean? I’m glad for that, but Google’s stand is not for Chinese human rights; it is against its business getting hacked. That’s fair, but let’s realize that Google’s loosening of censorship is retaliation against hacking, not a newfound spirit of goodwill.

As China’s consumer spending is a small portion of its GDP relative to U.S. levels, China represents a huge source of advertising revenue. That’s big bux for Google. Still, Google is hardly the juggernaut in China that it is in the U.S.

Google has 33 percent of the market share behind Baidu’s leading 67 percent. Baidu is the most popular search engine on the Chinese internet: 77 percent of internet users use it to search while only 13 percent use Google.

Google isn’t going to lose its shirt if it loses China, but if can make inroads on the Chinese government then it will demonstrate that it is equally as powerful as American foreign policy (perhaps even more powerful in the wake of the Copenhagen Climate Change Conference where Obama was snubbed by President Hu Jintao and forced to negotiate with a lesser government official).

The logic will go like this: what’s good for Google is good for the U.S., and vice-versa.