A Little Thing Called General Equilibrium

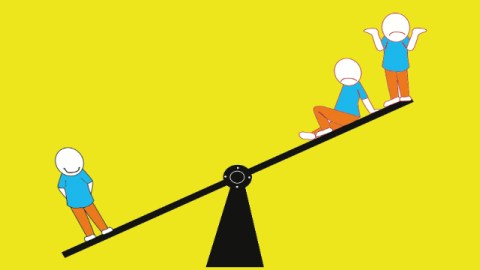

Economic growth is a tough thing to control if the tools you’re using only deal with one part of the economy. The problem is that when you push on one end of an economy, you might be pulling on the other, and vice versa. It’s a lesson that people who work in international development are finally learning – the hard way.

Exhibit A is the Millennium Villages Project, an initiative backed by the United Nations and led by Jeffrey Sachs of the Earth Institute at Columbia University. The project spent millions trying to improve crop yields in rural villages across Africa, and research by its backers apparently showed (there is much debate about the results) that farm productivity did indeed improve. But last week a paper was published in the Netherlands suggesting that in one Kenyan village, Sauri, the project did not achieve its ultimate objective: to raise incomes.

How can this be? In a rural village, when crop yields go up you’d expect incomes to rise as well. But as Michael Clemens of the Center for Global Development explained, the subsidy to farming also “caused less diversification of household economic activity into profitable non-farm employment, tending to decrease household income.” To economists, this situation embodies the difference between partial equilibrium (the situation in one market) and general equilibrium (the situation across an entire economy). Does subsidizing apple production increase economic growth? It might increase apple production, but people might shift resources away from orange production, too.

Microfinance, once viewed as a panacea for the economic problems of the poor, may also suffer from a general equilibrium problem. Even though extending credit to poor women has allowed many thousands of them to start small businesses and invest in household essentials, it hasn’t been proven to reduce poverty. Part of the issue appears to stem from a shift of resources away from other household activities and toward the new endeavors enabled by the loans women receive. As David Roodman, also from the Center for Global Development, wrote in 2009, “We have just one strong study of group credit for the truly poor, for instance, and it only shows us effects about one year out. Claims that microcredit is a proven anti-poverty intervention thus seem dubious.” And a more recent review from the University of London found no “convincing impacts on well-being.”

Finally, the growing academic literature about the effects of migration has stumbled when it has neglected general equilibrium effects. A study published last week by the British Medical Journal suggests that countries whose doctors emigrate are losing a substantial part of the return on their investment in the doctors’ training. Among the study’s methodological problems is a failure to account for the all the components of the return, either to the investing countries or to their governments. Migrant doctors typically practice in their home countries for several years before emigrating; they often send money back to their families and friends; many of them come back to their home countries; and their learning abroad helps to raise the quality of care at home through the sharing of ideas and information. Their emigration affects many markets, not just the market for doctors’ human capital. Ignoring the others may have led this study’s authors to the wrong conclusion.

Many researchers who work in international development have a strong grounding in microeconomics, so they know how to look at the dynamics of one market at a time in minute detail. But accounting for general equilibrium effects means looking at the macroeconomy, whether in an entire country, a small village, or just one household. Even that single household encompasses many markets, and a single intervention to raise living standards can easily affect them all.