judaism

Spirituality can be an uncomfortable word for atheists. But does it deserve the antagonism that it gets?

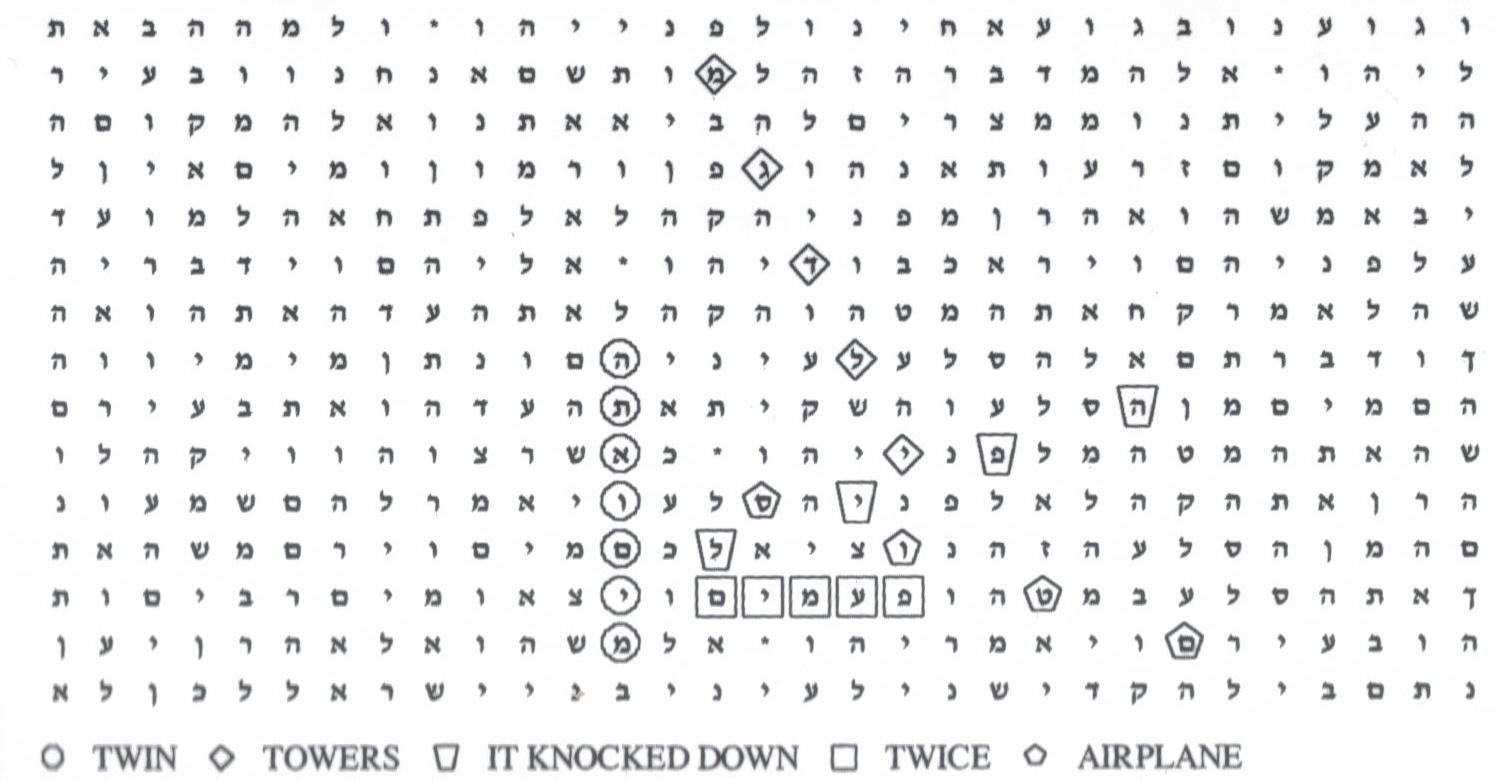

The controversy around the Torah codes gets a new life.

Have you heard the one about the U.S. Open and Yom Kippur? You’re about to.

▸

5 min

—

with

Rabbi Darren Levine explains how the psychology of happiness intersects with religious practice.

▸

8 min

—

with

Faith is absurd — let’s embrace the comedy in that.

▸

4 min

—

with

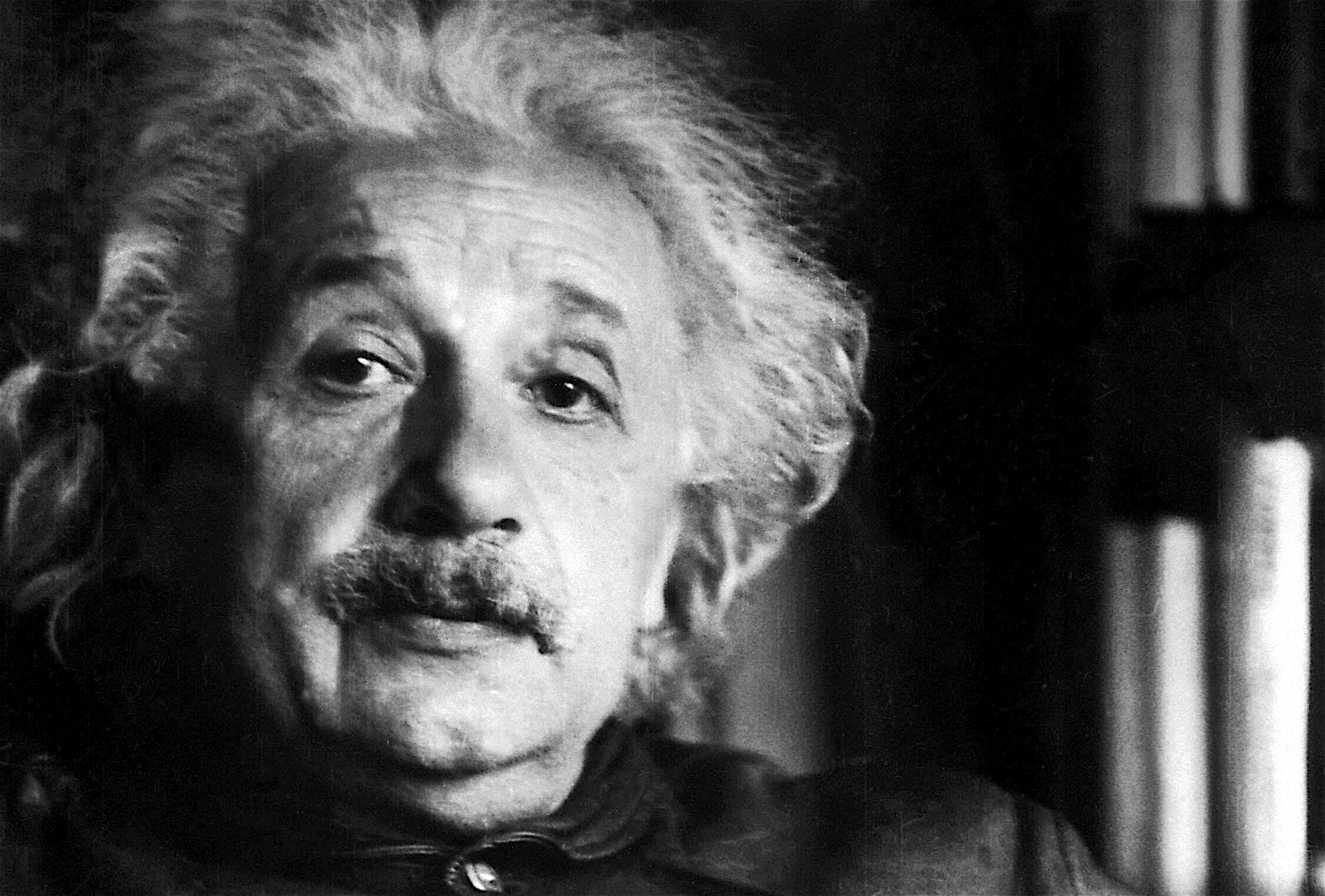

Albert Einstein shared his thoughts on the meaning of life and his own spiritual views.

For nearly 50 years, a charred lump of Dead Sea Scrolls has been sitting in a lab, too brittle to unroll. Now it’s been virtually unwrapped using 3D technology, and the contents are intriguingly – and significantly – petty.