free speech

How America became a fragile nation — and how it can get its resilience back.

▸

9 min

—

with

Most people seem to enjoy liberalism and its spin offs, but what is it exactly? Where did the idea come from?

7 scholars and legal experts dissect what you can and can’t say in America.

▸

22 min

—

with

The idea behind the law was simple: make it more difficult for online sex traffickers to find victims.

A new look at existing data by LSU researchers refutes the Trump administration’s claims.

What speech is harmful, how do we know, and what do we do if we find out?

Americans say we value free speech, but recent surveys suggest we love the ideal more than practice, a division that will harm more than it protects.

Do you know your rights? Hit refresh on your constitutional knowledge!

▸

2 min

—

with

The ability to say what we want, when we want, is an important part of American democracy.

▸

2 min

—

with

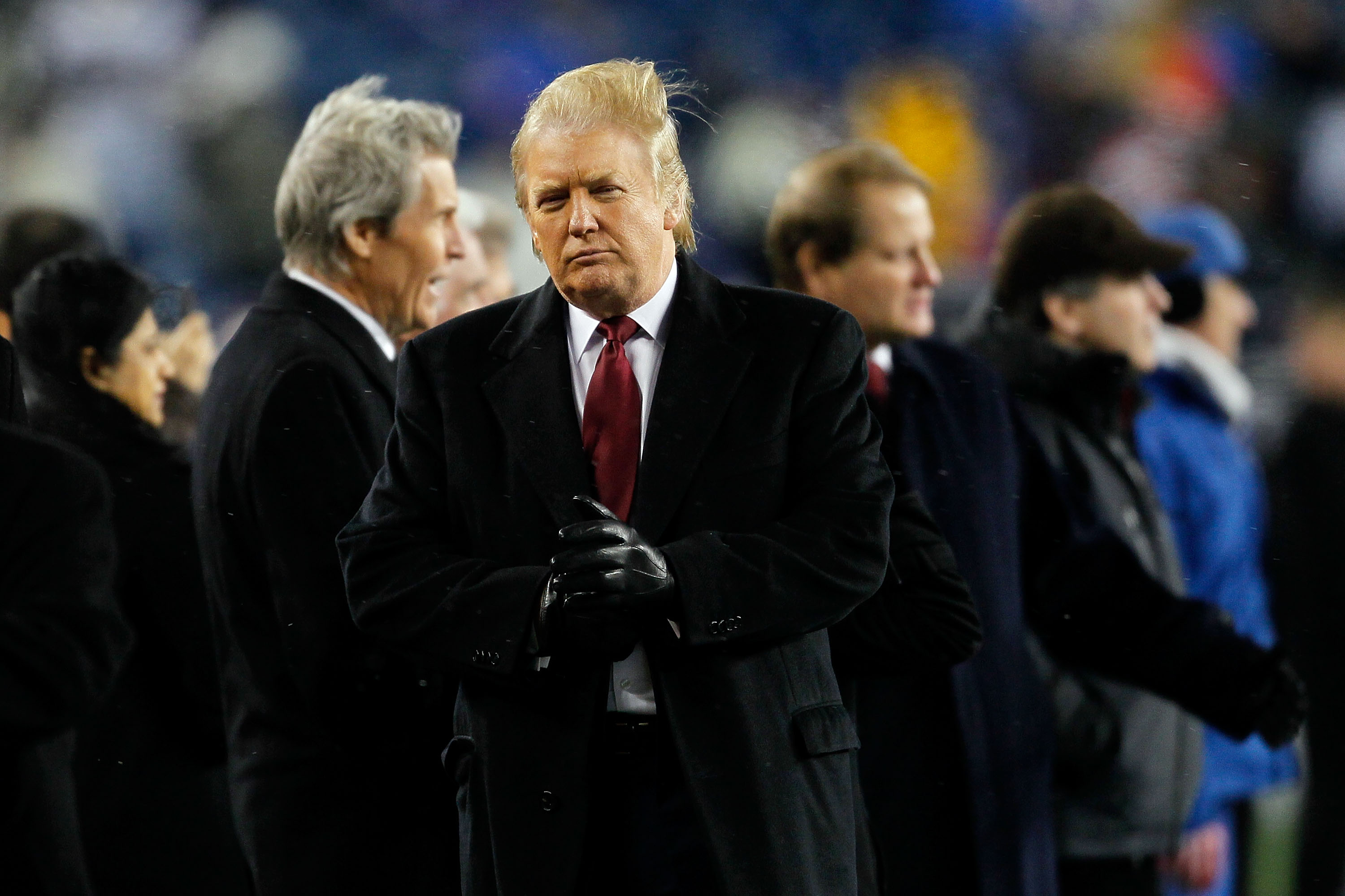

Several interpretations of the Constitution say that Trump has already broken the law by threatening free speech concerning the NFL. When can we start impeachment proceedings?

A new study questions why some people support “free speech”.

Limiting speech doesn’t change the nature of hate, says Josh Lieb. Thoughts can be hateful and stupid—but should they be criminal?rn

▸

3 min

—

with

No offense, says Slavoj Žižek, but maybe we need to incorporate some “gently racist” icebreakers into our conversations.

▸

10 min

—

with

The ranking of empathy from highest to lowest goes liberals, conservatives, libertarians. But the difference is minor, says Paul Bloom. Typically the debate isn’t all over whether or not to empathize – it’s over who to empathize with.

▸

5 min

—

with

Can you legislate for good human behavior, or does proposing laws to imprison those who use racial slurs distract from actual progress?