competition

The size of rabbits and hares has long been evolutionarily constrained by competitors roughly their size.

Imagine poisoning your rival and yourself and giving only yourself the antidote.

The study shows when the ‘Napoleon complex’ is most likely to emerge.

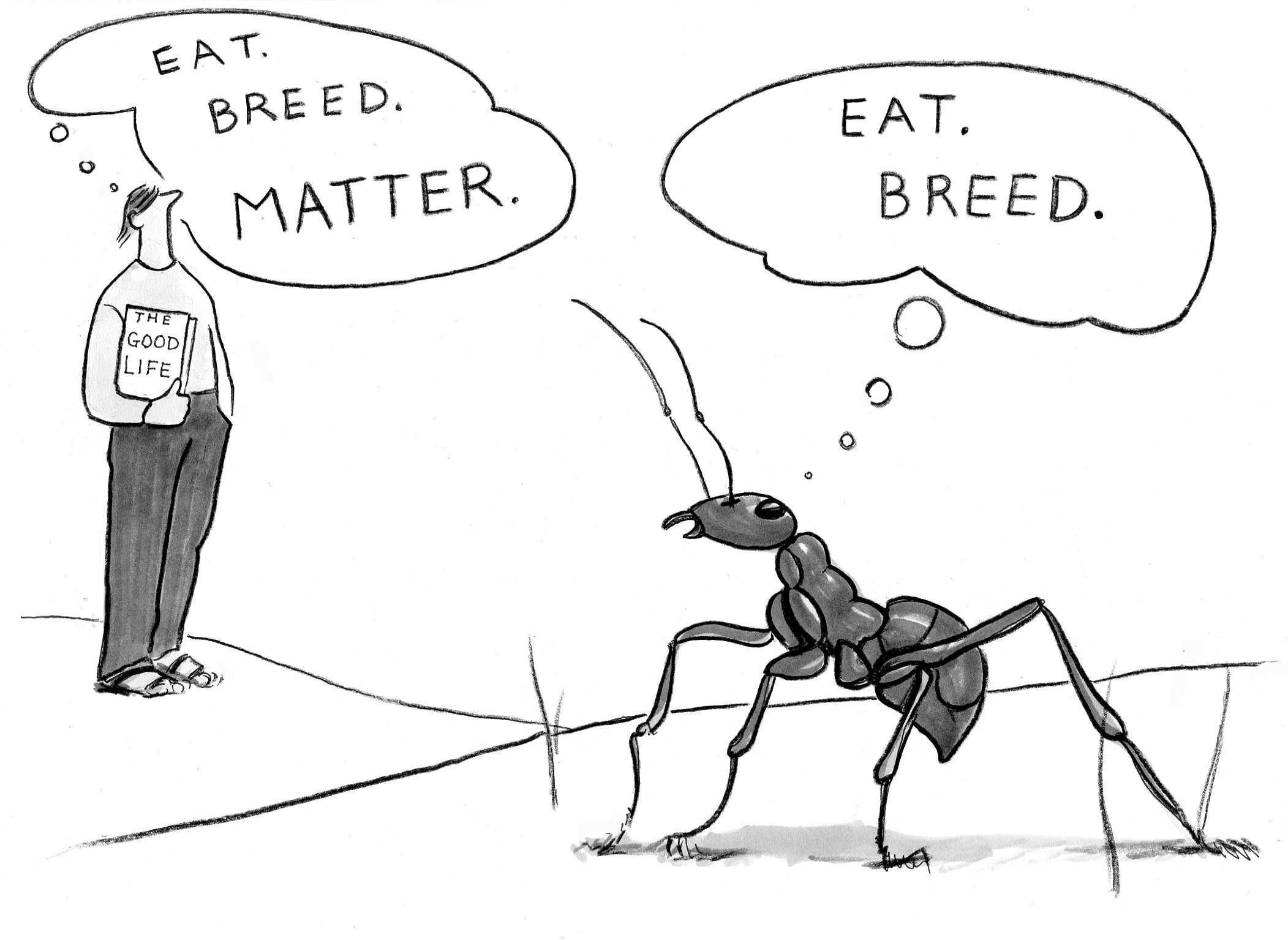

Natural “narrative selection” was key to turning insignificant apes (who had tools for 2 million years) into the species that now dominates the bio-sphere.