Black Lives Matter

The English Department is instituting a series of reforms that cuts across the entire university.

Among other things, researchers found that there are two subgroups of the Alt-Right, but that the more economically motivated members may buy into White Supremacy over time.

Billionaire George Soros, the subject of countless conservative conspiracy theories, funds the opposition to President Trump’s agenda.

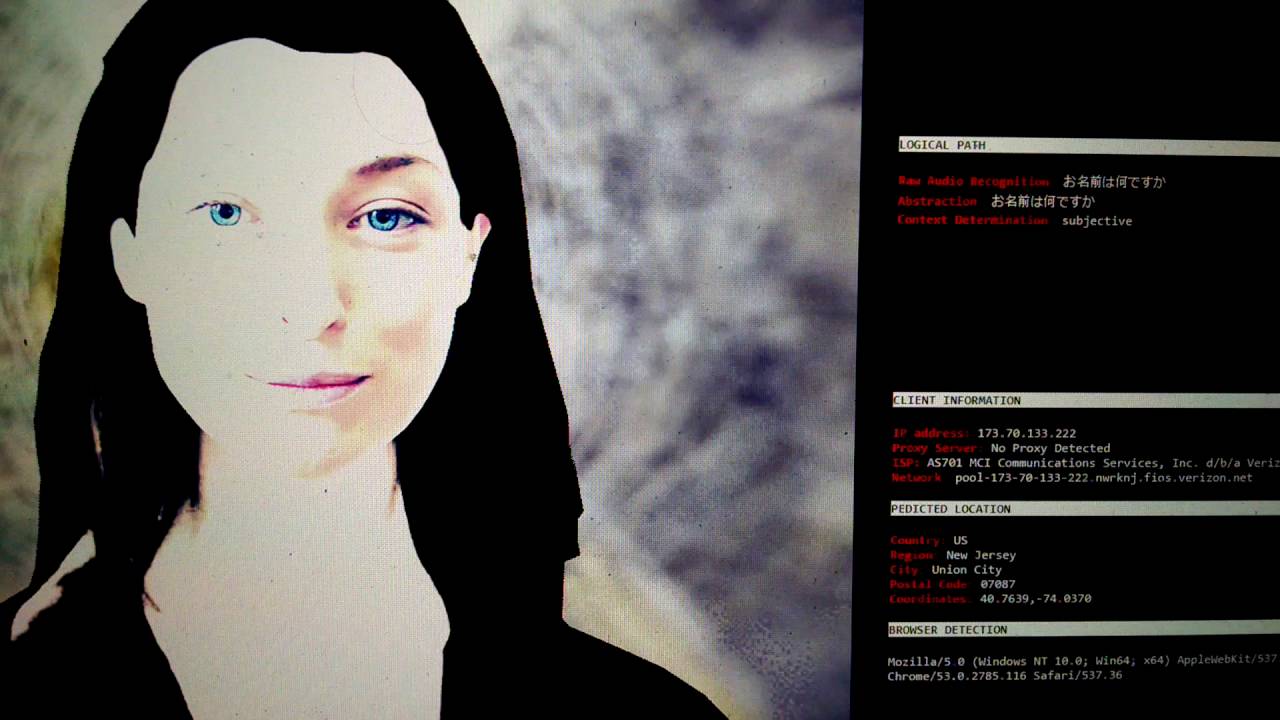

This AI hates racism, retorts wittily when sexually harassed, dreams of being superintelligent, and finds Siri’s conversational skills to be decidedly below her own.

Before we had the right to vote, we had the right to protest, says journalist Wesley Lowery.

▸

6 min

—

with

Journalist Jelani Cobb considers the impact of Obama’s presidency on race in America. Did he make good on the promise of change that got him elected?

▸

6 min

—

with