bees

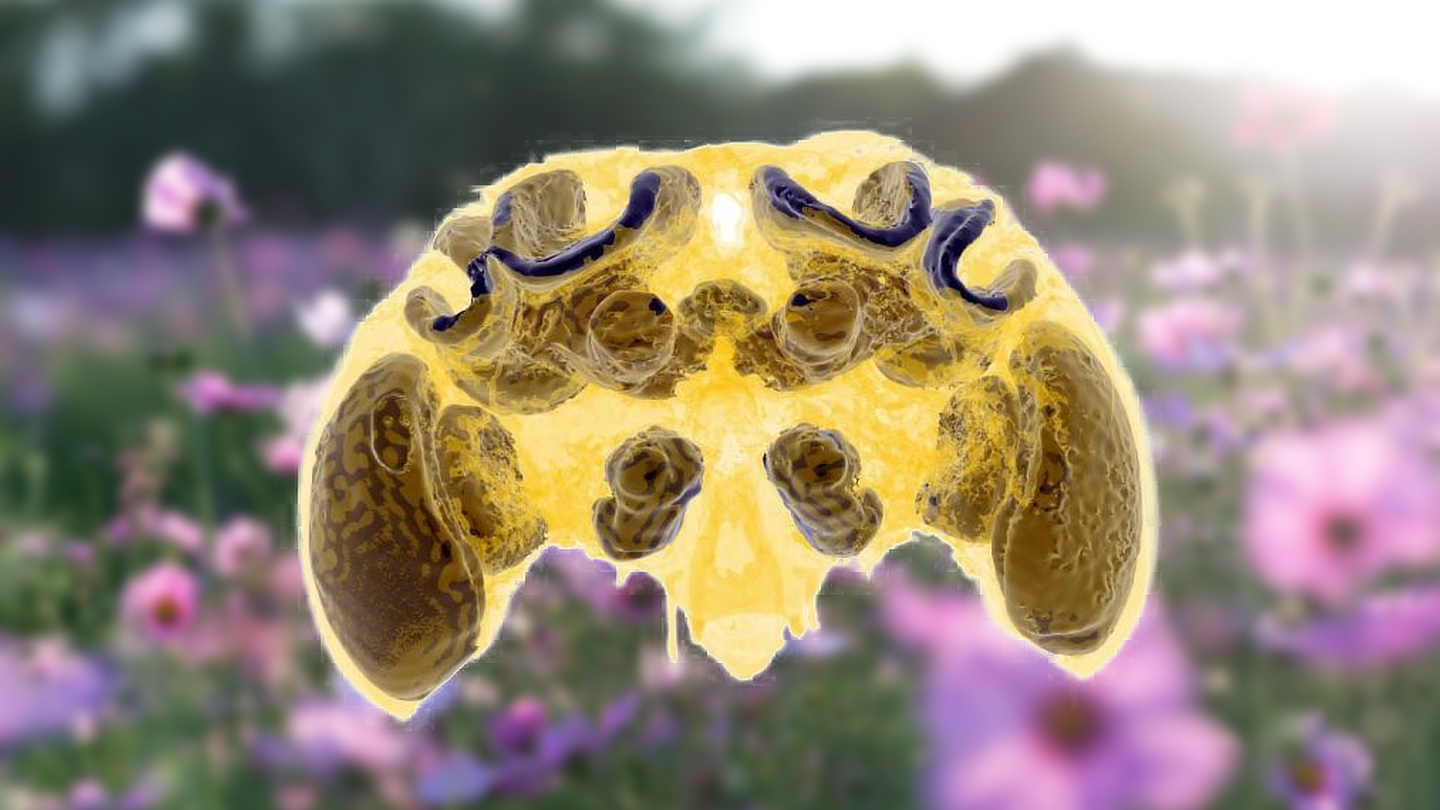

Researchers develop a fungus that kills mites that contribute to honey bee Colony Collapse Disorder.

It’s time to rethink how satellites and other objects are made and eventually destroyed.

▸

5 min

—

with

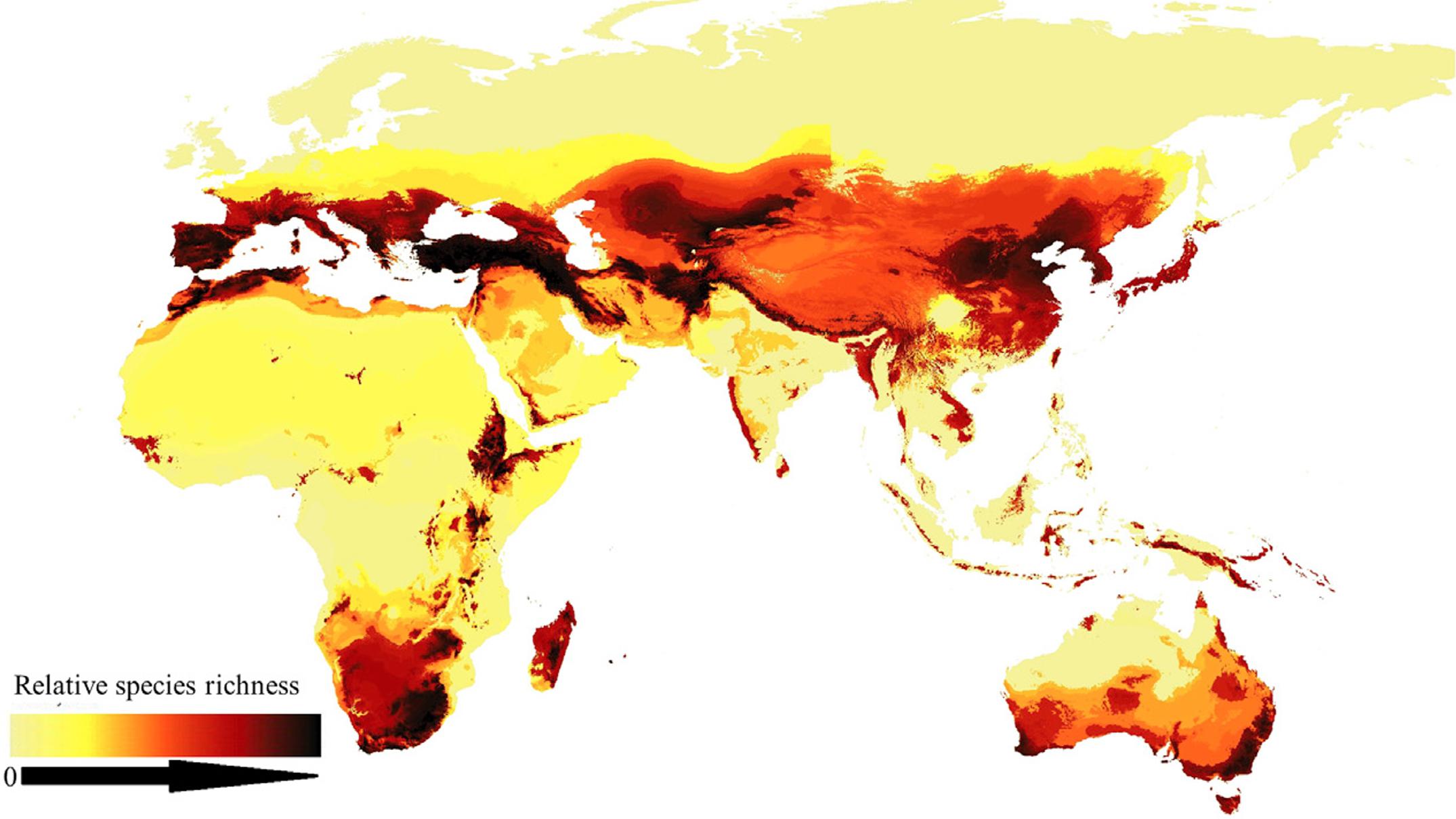

First picture of worldwide bee distribution fills knowledge gaps and may help protect species.

An active component of honeybee venom rapidly killed two particularly aggressive forms of breast cancer in a laboratory study.

Declining bee populations could lead to increased food insecurity and economic losses in the billions.

Study finds that a colony’s exposure to pesticides impairs offspring.

2018’s winter was particularly harsh on U.S. honeybees. What’s causing bee populations to plummet, and what can we do about it?

The controversial herbicide is everywhere, apparently.

A buzzworthy study looks at the strange actions of bees.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service believes a species of bumble bee – the rusty patched bumble bee – should be under federal protection under the Endangered Species Act.