The First Gene Editing Procedure Has Begun in Humans

“It’s kind of humbling,” says Brian Madeux of being the first patient to have doctors attempt to edit genes inside his body.

The experimental treatment aims to cure his Hunter syndrome, a genetic disorder that can cause “permanent, progressive damage affecting appearance, mental development, organ function and physical abilities,” according to Mayo Clinic’s article on the disease.

The procedure was performed on Madeux on November 13 2017, at UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital in Oakland, CA. According to team leader Paul Harmatz , doctors only needed to repair 1% of Madeux’s liver cells to cure his condition, so they’re hopeful. The experiment is not without danger, though, even if it’s worth it to Madeux, whose condition has made life something of a nightmare. “I’m willing to take that risk,” the 44-year old chef says, “Hopefully it will help me and other people.”

The team says they could have their first indicator of the procedure’s success in mid-December, and fully expect to know for sure by February 2018.

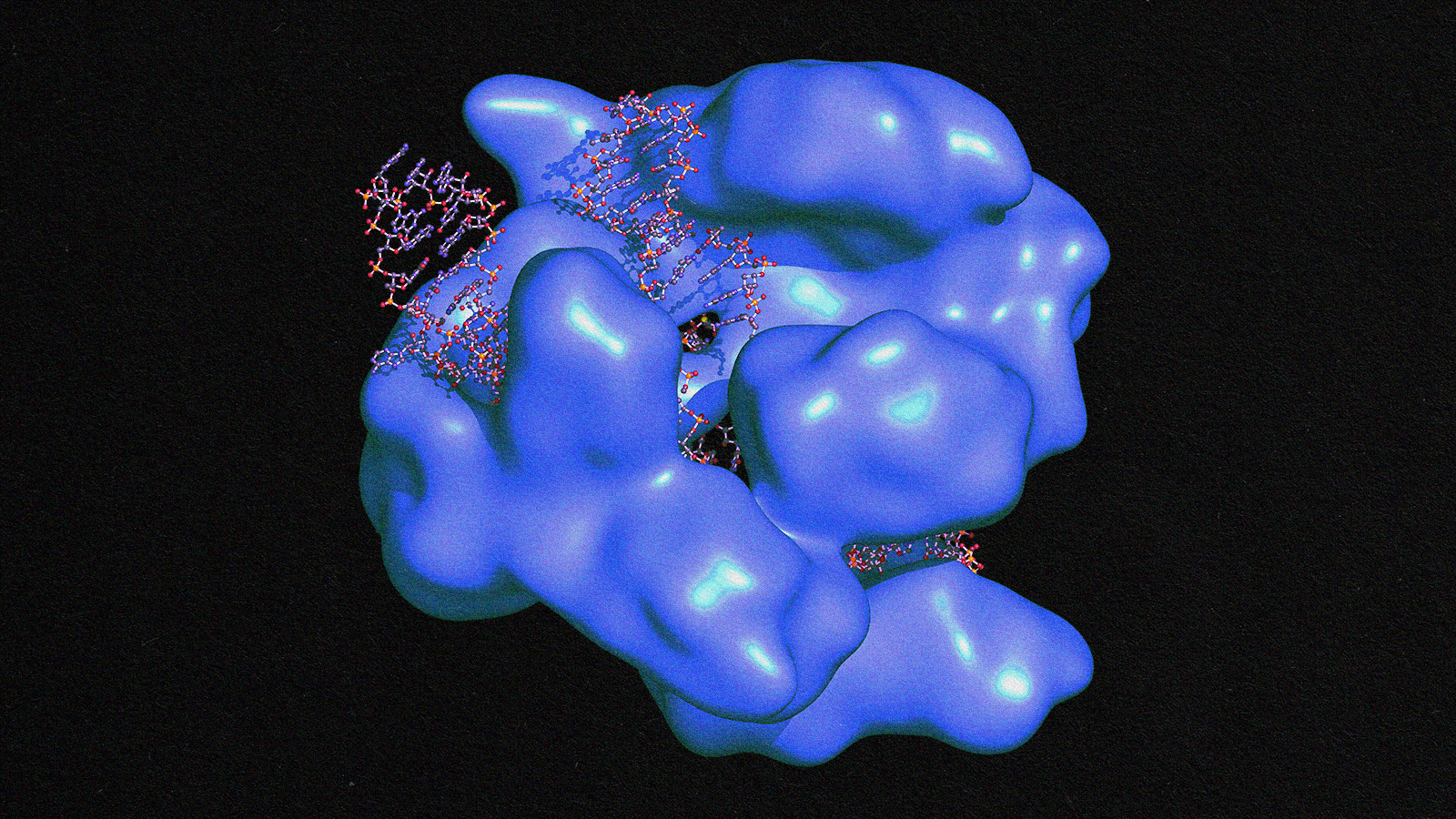

The doctors administered Madeux a three-hour drip containing a virus that had been modified not to cause infection. It carried to his liver billions of copies of DNA instructions for creating a corrective gene, and for two “zinc finger” nuclei that can snip out the defective gene and replace it with the new corrective one. (Zinc finger editing is not completely dissimilar to the better-known CRISPR-Cas9 editing method in that it, too, can target and snip out unwanted genetic material.) The team wore protective clothing during the IV drip to help ensure they didn’t infect Madeux with anything.

Sandy Macrae, president of Sangamo Therapeutics, describes the process this way: “We cut your DNA, open it up, insert a gene, stitch it back up. Invisible mending. It becomes part of your DNA and is there for the rest of your life.”

Which also means that if there are unintended consequences — and of course our understanding of gene editing is still in the really stages — the patient is stuck with them. It’s possible something could go wrong in the gene-editing process, and it’s possible that something surprising could result in another malfunction of some sort, or in cancer. This uncertainty is one of the dangers Madeux faced in agreeing to this experiment.

The other is that the virus that delivered the repair materials could conceivably provoke a deadly immune system reaction like the one that killed Jesse Gelsinger in a more limited 1999 experiment. Madeux’s doctors used a different virus from Gelsinger’s, though, and it’s so far proven to be safe in other experiments.

Hunter syndrome is caused by a misbehaving or missing enzyme for cleaning out certain carbohydrates. Without the enzyme, these carbohydrates build up, causing more and more problems. People with diseases like Hunter syndrome tend to die young. It’s a terrible affliction characterized by frequent colds and ear infections, loss of hearing, heart issues, breathing issues, malformed bones and joints, bowel problems, mental-clarity impediments, and skin and eye problems. Symptoms can be reduced somewhat with weekly injections of the enzyme, but that can cost $100,000 to $400,000 yearly and has no effect on the brain issues that Hunter syndrome can cause. Most of its victims live brief, highly constrained lives.

Madeux’s experience has been fairly typical, with him nearly dying about a year ago from a severe bronchitis/pneumonia episode. “It seems like I had a surgery every other year of my life,” he tells AP. “I was drowning in my secretions, I couldn’t cough it out.” Madeux’s had 26 operations over the years for Hunter-caused problems, and this gene therapy offers the only possible cure. Madeux’s ready to consign this awful syndrome to the past: “I’m nervous and excited. I’ve been waiting for this my whole life, something that can potentially cure me.”

He’s not the only one excited, of course. Doctors hope Madeux will be just the first of many patients to get relief from horrible, now-incurable genetic diseases.

—