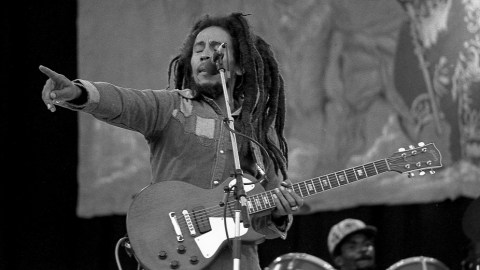

Study: Empathetic people process music differently, enjoy it more

It’s no surprise our level of empathy impacts how we process social interactions with other people. But how might empathy affect the way we process music?

That’s the question addressed in a first-of-its-kind study published in Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. The results showed that high-empathy people not only got more pleasure from listening to music, but also experienced more activity in brain regions associated with social interactions and rewards.

The implication is that empathy can make you interact with music as if it were a person, or a “virtual persona,” as described in a 2007 study:

“Music can be conceived as a virtual social agent…listening to music can be seen as a socializing activity in the sense that it may train the listener’s self in social attuning and empathic relationships.”

The researchers conducted two experiments to examine how empathy impacts the way we perceive music. In the first, 15 UCLA students listened to various sounds made by musical instruments, like a saxophone, while undergoing an fMRI scan.

Activation sites correlating with trait empathy (IRI subscales) in selected contrasts.

Some of the instrument sounds were distorted and noisy. The idea was that the brain might interpret these sounds as similar to the “signs of distress, pain, or aggression” that humans and animals emit in stressful scenarios, and these “cues may elicit heightened responses” among high-empathy people. Participants also completed the Interpersonal Reactivity Index, a self-reported survey commonly used by scientists to measure one’s level of empathy.

The results confirmed what the team had hypothesized: listening to the sounds, even outside of a musical context, significantly activated empathy circuits in the brains of high-empathy people. In particular, the sounds triggered parts of the brain linked to emotional contagion, a phenomenon that occurs when one takes on the emotions of another.

But how does empathy affect the way we listen to a complete piece of music?

To find out, the researchers asked students to listen to music that they either liked or disliked, and which was either familiar or unfamiliar to them. Results showed that listening to familiar music triggered more activity in the dorsal striatum, a reward center in the brain, among high-empathy people, even when they listened to songs they said they hated.

Familiar music also activated parts of the lingual gyrus and occipital lobe, regions associated with visual processing, prompting the team to suggest that “empathic listeners may be more prone to visual imagery while listening to familiar music.”

In general, high-empathy people experienced more activity in brain regions associated with rewards and social interactions while listening to music than did low-empathy participants.

“This may indicate that music is being perceived weakly as a kind of social entity, as an imagined or virtual human presence,” said study author Zachary Wallmark, a professor at SMU Meadows School of the Arts. “If music was not related to how we process the social world, then we likely would have seen no significant difference in the brain activation between high-empathy and low-empathy people.”

We often conceptualize music as an abstract object for aesthetic contemplation, Wallmark said, but the new findings could help us reframe music as a way to connect others, and to our evolutionary past.

“If music can function something like a virtual “other,” then it might be capable of altering listeners’ views of real others, thus enabling it to play an ethically complex mediating role in the social discourse of music,” the team wrote.