The formula that predicts every animal’s life story

Image source: Winggo Tse/Unsplash; HelloRF Zcool/Komsan Loonprom/Pixeljoy/Shutterstock; Big Think

- Earth’s species diversity is stunning, but there are a couple of battles we all face.

- Our response to these challenges set the course of our lives.

- Plug in a couple of variables, and a new formula predicts how we live, reproduce, and die.

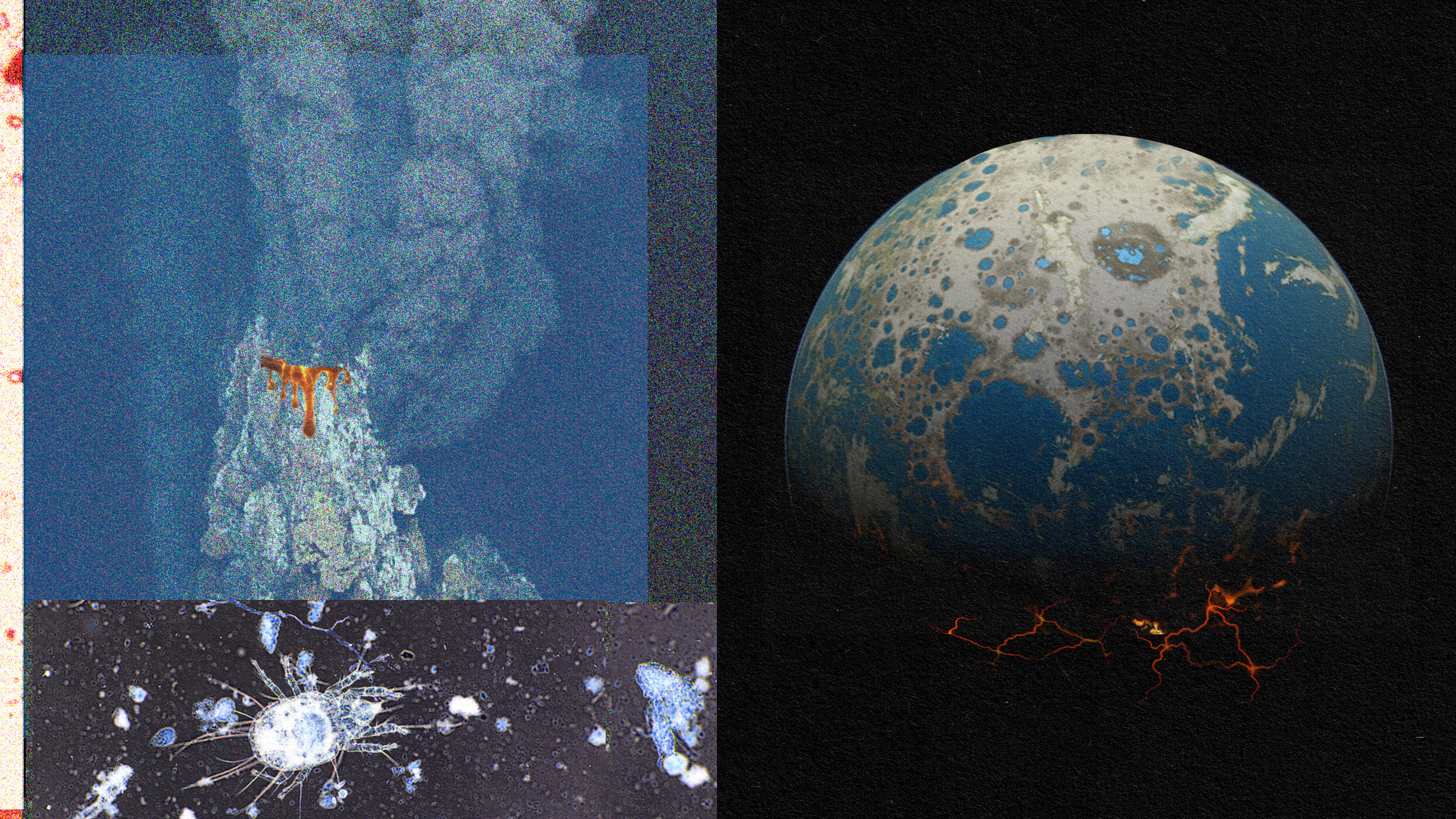

The diversity of life on Earth is mind-boggling. What could humans, octopuses, birds, and plankton possibly have in common? Well, the truth is that all of us/them have evolved to overcome some of the same biophysical constraints. As a result, says a study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, certain universal rules can be derived that encompass all of our life histories.

“If you impose these constraints on the mathematical model, then certain unifying patterns fall out,” says ecology and evolutionary biology postdoctoral fellow Joseph “Robbie” Burger, of the Institute of the Environment and the Bridging Biodiversity and Conservation Science program at the University of Arizona.

Image source: Budimir Jevtic/Shutterstock

Our common struggles

“The life histories of animals reflect the allocation of metabolic energy to traits that determine fitness and the pace of living. Here, we extend metabolic theories to address how demography and mass–energy balance constrain allocation of biomass to survival, growth, and reproduction over a life cycle of one generation.” — Burger, et al

These challenges present themselves in different ways in different habitats, and so our responses vary. Nonetheless, we all aspire to survive for a while, reproduce, and get out of the way of our offspring. Whether one is a turtle laying millions of eggs on a beach or an elephant giving birth to one calf at a time, our goals are essentially the same.

The study begins with an axiom: “Energy is the staff of life.” The sustainable allocation of energy is therefore something all species need to establish in order to survive. According to the study, there are two areas in which workable tradeoffs have to be found for any creatures:

- A “mass–energy balance. . . so that over a lifespan in each generation, all of the energy acquired. . . is expended on respiration and production, and energy allocated to production exactly matches energy lost to mortality.”

- A “constraint on mortality so that, regardless of the number of offspring produced, only two survive to complete a life cycle of one generation.”

Image source: Ihnatovich Maryia/Shutterstock

Predicting a species’ life cycle

Burger and his colleagues derived a predictive formula informed by a species’ response to the two constraints.

“What’s so cool about these equations,” says Burger, “is that to solve it, all you have to know are two values — the size of the offspring at independence and the adult size. If you plug that into the equation, you get the number of offspring an organism will produce in a lifetime [as well as] myriad other life history characteristics.”

Assembling and analyzing a database of 36 animals’ life histories, Burger and his colleagues were able to create a formula that can accurately predict a number of things about any species’ life story:

- the length of a species’ single generation

- the species’ mortality rate

- the number of offspring the species reproduces and the size of the offspring

- the type and extent of parental care common to the species

Prior to the new study, the only widely used formula had been the notion that the smaller the offspring the more of them there were, and vice versa. Burger’s finding indicate that things are not quite that simple.

The new formula is of more than academic importance. As we work to understand habitat changes caused by humankind and the species they impact, and as we seek to help those species survive, knowledge of their natural life cycles is invaluable, particularly given the incredible variety of life forms involved, many of whose life stories remain largely hidden from us.

“We now need to put these equations to practice,” asserts Burger, “by developing user-friendly programming tools, collaborating with field scientists refine ecosystem models and informing management decisions.”