What is life like elsewhere in the Universe?

- The laws of physics and chemistry are the same across the Universe.

- Life is bound to follow certain biochemical rules, and the details of how it unfolds are contingent on its host planet’s properties and history.

- It follows that no two worlds can have the exact same kinds of living creatures. More amazingly, we are the only humans in the Universe.

Let’s start with a couple of important disclaimers: First, I am following an operational definition of life as any self-sustaining chemical reaction network capable of metabolizing energy from the environment and of reproduction following Darwinian natural selection. So, no spiritual machines way more advanced than we are or bizarre, star-dwelling intelligent clouds or wormhole-inhabiting swarms of nanobots. Flying spaghetti monsters are fine, as long as they have a biochemical metabolism of some sort.

Alien life, if it exists, may surprise us in unexpected ways, and that would be amazing. But if it is really different from what we are used to here, we probably will fail to detect it for a while. (NASA has been funding very innovative research on how to detect unexpected life forms elsewhere.) I am also restricting our range to our cosmic horizon — that is, the sphere with a radius equal to the distance light has traveled since the beginning of time some 13.8 billion years ago. Factoring in the expansion of the universe, this radius is about 46 billion light-years. So, no multiverse stuff. We are trying to be as concrete as possible.

The universality of the Universe

Perhaps the most striking result of modern science is that the same laws of physics and chemistry apply across the Universe. We are now able to look at stars and baby galaxies billions of light-years away from us and billions of years old, and we find that they have the same chemical elements (albeit in different relative ratios) and that these stars evolved according to the same dynamic laws as our own Sun.

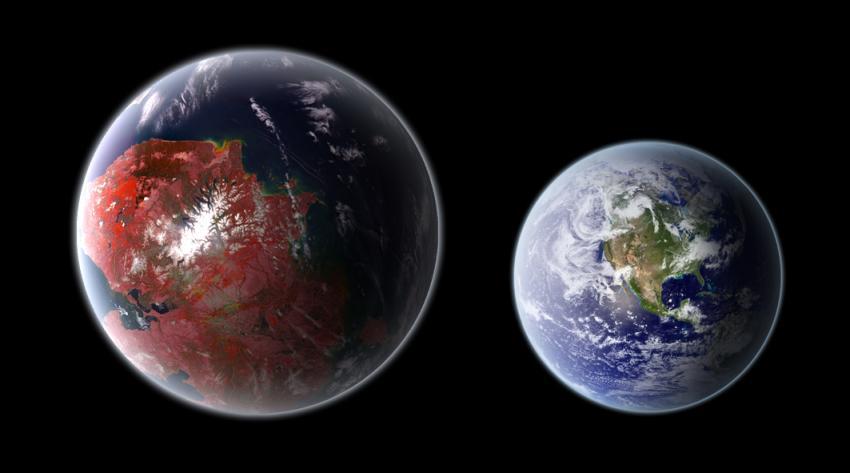

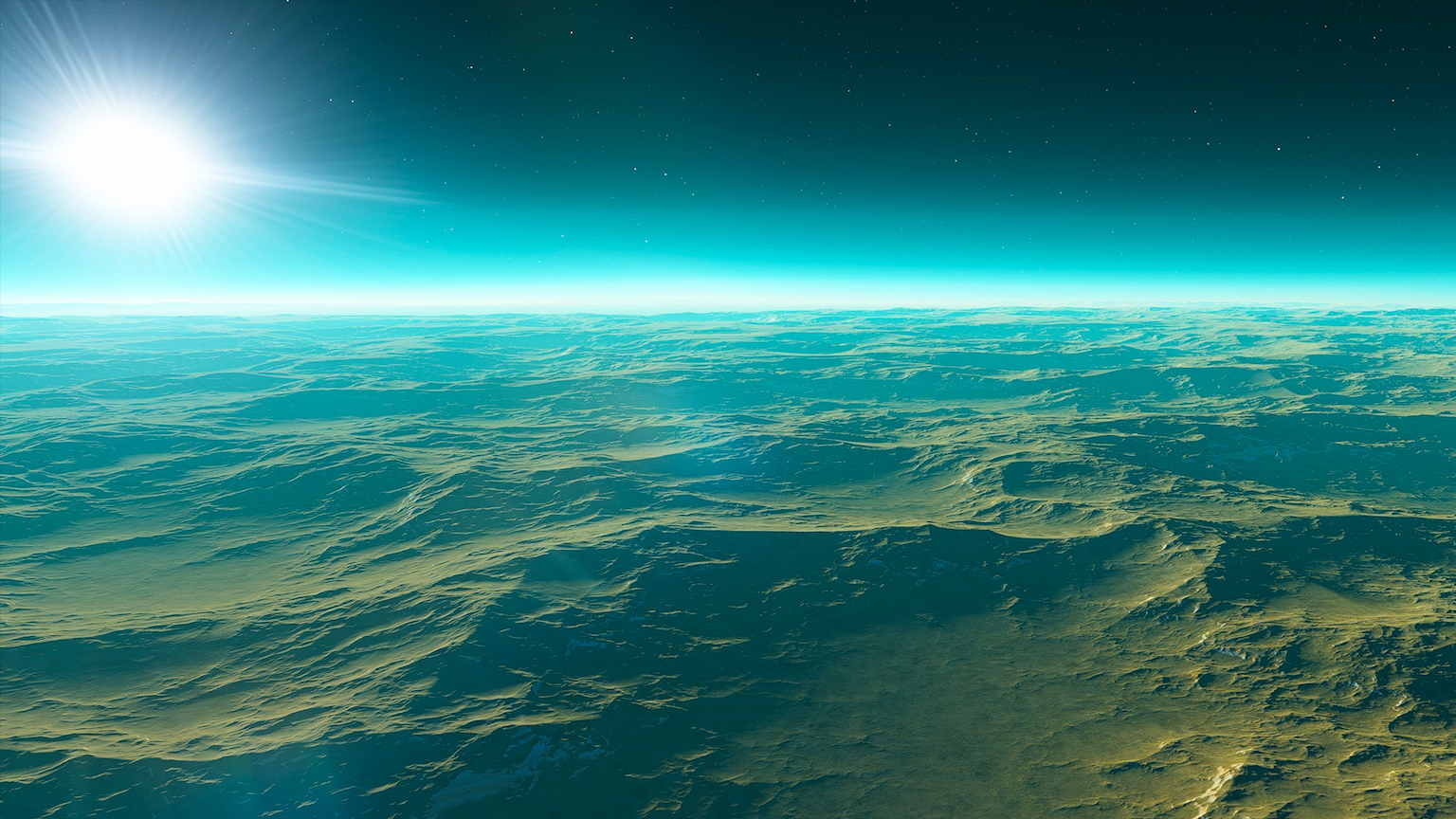

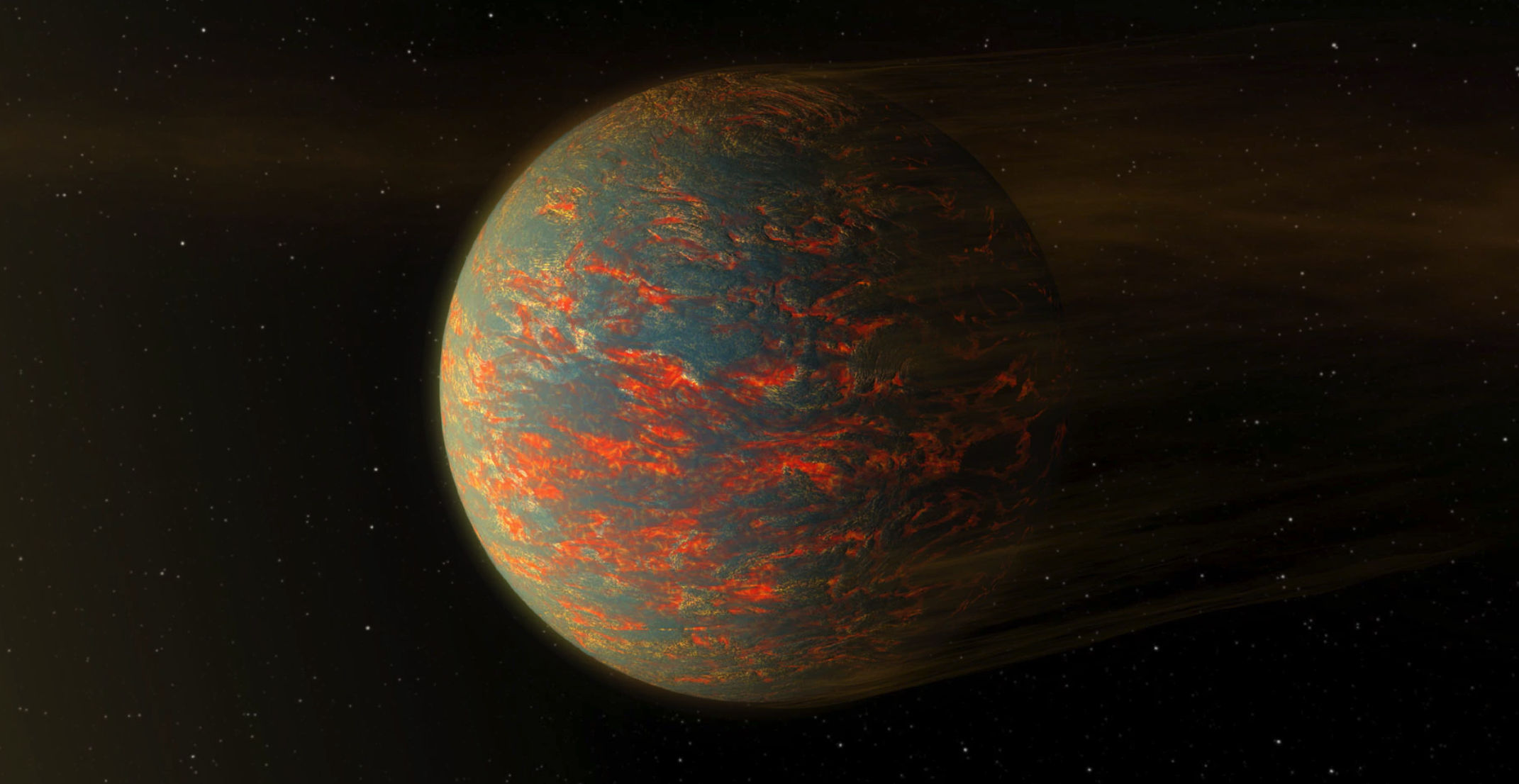

Because of the universality of the physical laws, most stars come with a court of planets, and planets tend to have moons. Each is its own world, with different physical properties and chemical makeup. There are large and small planets, rocky and gaseous, with many moons or just a few or none. Planets may spin with a large or small tilt (the Earth’s is 23.5° from the vertical, while that of Uranus is an amazing 97.7°), have thicker or thinner atmospheres with different gases in it, and so on. Just like Earth, as a planet evolves, so does its atmospheric composition. Thus, there is a staggering diversity of worlds out there in the Universe. Just in our own Milky Way galaxy, there should be about a trillion worlds, each a unique entity.

Trillions and trillions

To these we add the hundreds of billions of other galaxies within our cosmic bubble, and we arrive at trillions of trillions of worlds in our universe, give or take a factor of 100. (Side note: the number of worlds is close to Avogadro’s number, the number of atoms in one gram of hydrogen.)

Given the huge numbers, it would be easy to get carried away and conclude that everything is possible, that life will use every possible trick out there to exist. But things are not so simple. While the laws of physics and chemistry allow for similar processes to unfold across the Universe, they also act to limit what is possible or viable. Even if science doesn’t allow us to completely rule out what cannot exist, we can use the laws of physics and chemistry to infer what might. Case in point: The flying spaghetti monster is a plausible cousin of the octopus that ventured out of the pond some billions of years ago on planet Mumba and, after some millions of years of random mutations and adaptive challenges, grew feathers on its tentacles and took flight. Or, if not feathers, some ballooning mechanism with hot air from its digestive tract.

Requirements for life

With the launch of the mighty James Webb Space Telescope this week, what can we expect to find as we scan the vast collection of worlds and search for signs of living creatures? No one truly knows the answer to this question, although we can make educated guesses:

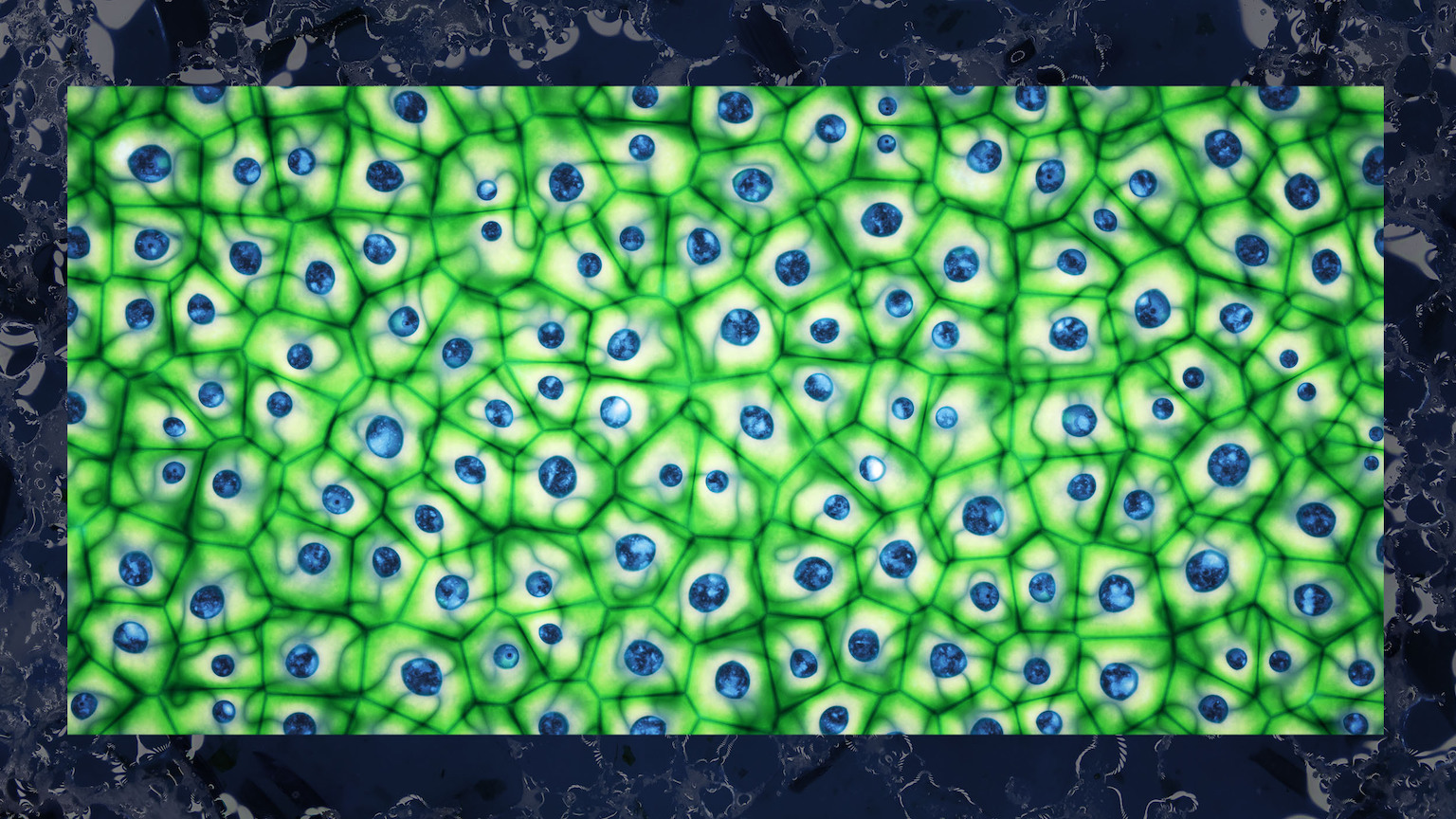

- Life will be carbon-based. Carbon is the easy-going atom, able to concoct all kinds of chemical bonds better than any other element. A poor imitation is silicon, but its biochemistry would be severely limited in comparison. Given that life needs versatility to thrive and adapt, it is a safe bet that carbon will be the skeleton of living beings anywhere.

- Life needs liquid water. Although there are frozen bacteria in the permafrost, they are not “living.” (Their metabolism is suspended.) Since life essentially is a biochemical reactor, it needs a solvent, a medium where ions can flow. Ammonia is sometimes proposed as a possibility. But it is a gas at room temperature and liquid only below -28° F at normal pressure. A cold planet with a heavy atmosphere could have liquid ammonia, but the jump from liquid ammonia to living creatures is unlikely. Water is a magical substance that is transparent, has neither smell nor taste, expands as it freezes (a key property for water-based life in colder climates, since there is liquid water below the ice), and is our own main ingredient.

From these two constraints, we conclude that the essence of life should be simple: carbon + water + other stuff (at a minimum nitrogen and hydrogen). The details, though, will probably vary and surprise us, as did the discovery of living creatures in deep thermal vents — creatures that use inorganic materials as their main energy source, as opposed to sunlight. Each planet that may contain life has its own history. And since we cannot separate a planet’s history from the history of life on it, each planet’s life will have its own unique history. This means that natural selection acts as a history-based pressure for survival, producing different tales that unfold in unpredictable ways.

A diverse Universe

Combined, the staggering planetary diversity and the historic contingencies for life’s evolution have an amazing consequence: there cannot be two planets with identical life forms. Furthermore, the more complex the life form, the lower the odds it will be replicated — even approximately — in another world.

It follows that we are the only humans in the Universe. Yes, there could (at least in principle) be other biped intelligent species with left-right symmetry out there, but they will not be like us. And if the flying spaghetti monster exists, it will exist only on one planet or moon as well.

What about intelligence? While intelligence is clearly an asset in the struggle for survival among different species, it is not a purpose of evolution; evolution has no purpose, no final goal. The dinosaurs were here for about 150 million years and, as far as we know, did not develop symbolic languages or the capacity to create technologies. Life is happy just replicating; with intelligence, it will be unhappy just replicating.

As creatures on a planet featuring a spectacularly rich biosphere, we are connected chemically to the rest of the Universe, sharing the same basis for life as other potential creatures out there. At the same time, we are unique, as are all other living creatures on this planet. Life is this amazingly complex phenomenon that, from a carbon-based code and a common genetic ancestor, creates a staggering diversity of wonders on this world and possible others. And we are the privileged living things that know this.