Henrietta Lacks: Life Everlasting?

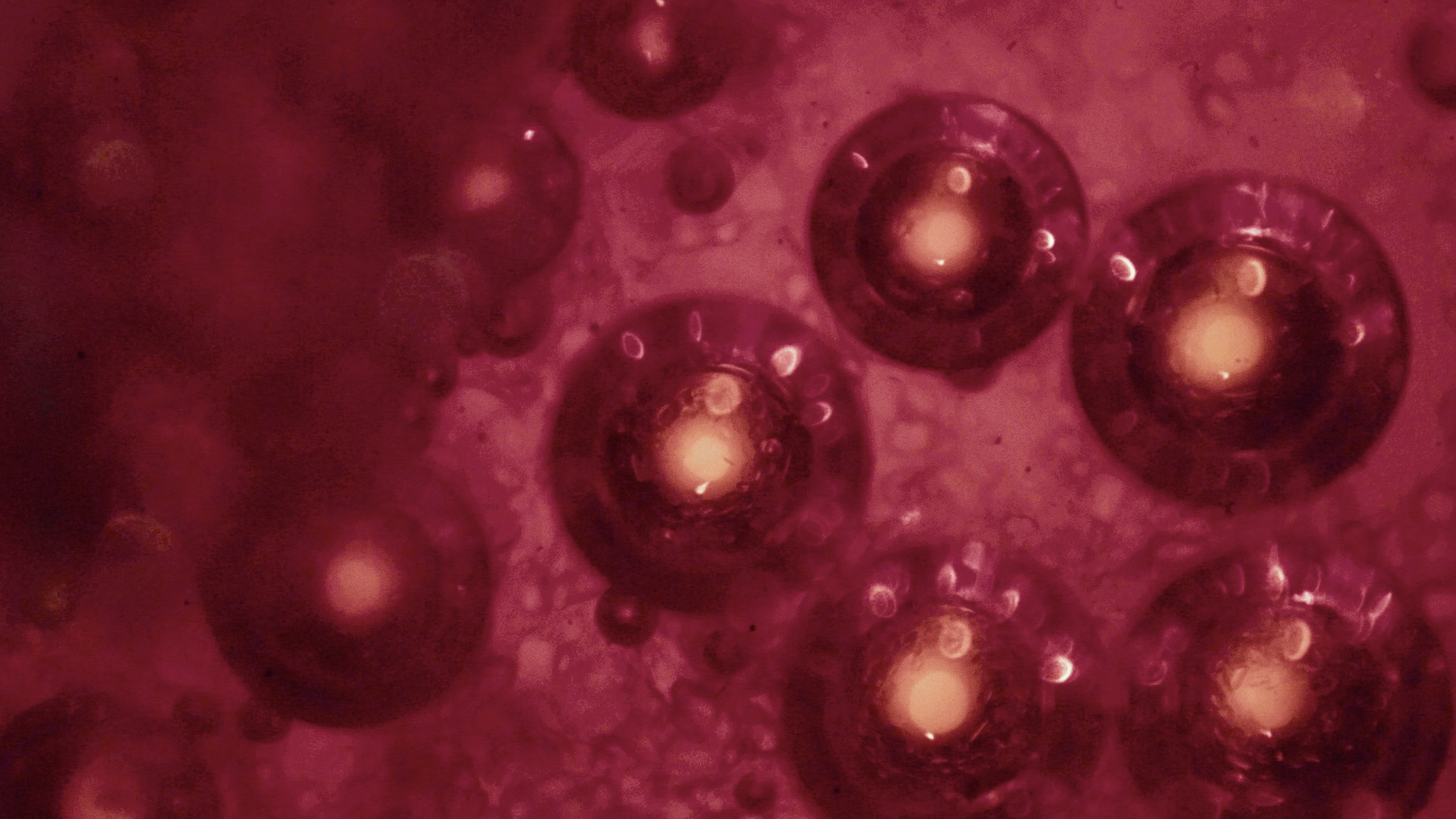

Henrietta Lacks, a thirty-one year old African American mother of five from Baltimore, died of cervical cancer in 1951. By the time she passed away, her cancer cells had been replicating themselves in petri dishes at a Johns Hopkins lab for months. Out of a portion of the tissue from her original biopsy, tissue diverted to the research university’s biomedical researchers without Mrs. Lacks consent, Drs. George and Martha Gey ended up generating the most famous line of cell cultures in the field of biology, the HeLa cell line. These were the first continuously cultured malignant cells in the world. This discovery has contributed enormously to medical research over the decades.

Normal protocol at that time for biomedical research did not include any standardized method for getting a patient’s consent in order to utilize their skin, bone, or other biological tissues in ongoing research experiments. So when Dr. George Gey announced his discovery on television the same day Lacks died, the irony of the moment was likely unknown to anyone other than he and his wife.

If you could pile all HeLa cells ever grown onto a scale, they’d weigh more than 50 million metric tons—as much as a hundred Empire State Buildings. HeLa cells were vital for developing the polio vaccine; uncovered secrets of cancer, viruses, and the effects of the atom bomb; helped lead to important advances like in vitro fertilization, cloning, and gene mapping; and have been bought and sold by the billions.

From The Immortal Life Of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot

The first thoughts flitting through my mind while I read the story of Henrietta Lacks was the Venus Hottentot exhibit. Sara Baartman was a Khosian woman from South Africa who had been working as a slave during the early nineteenth century when a British ship’s doctor persuaded her to accompany him to England, where he put her on display as a live freak show. She was known as the Venus Hottentot, and crowds flocked to see her nude form because of her unusually large buttocks and genitalia. After Baartman’s death, a French scientist pickled her genitals and brain and put them on display at the Musee de l’Homme in Paris.

As deliciously vengeful as it was to equate for a few seconds the biomedical researchers working with Lacks cell cultures to the men who pointedly set out to exploit Baartman because she had a phenotype different from the average European’s physical dimensions, I don’t see any real need at this juncture to demonize the 1950’s scientists because they didn’t use modern standards of informed consent.

The HeLa cells have remained at the heart of an age old bioethics debate — where does human life end and individual cell replication begin?

However, there is no longer any anonymity involved, and the Lacks family, along with the general public, has become aware of the tremendous importance Henrietta has played in modern medical research. This is the part of the Lacks story that will not allow me to completely banish the image of the Venus Hottentot from my head.

In the case of Sara Baartman, her remains were eventually returned to Cape Town in 2002, where she was buried. With the level of propagation of the HeLa cell line has reached by now, mounting a similar effort would prove fruitless. It remains to be seen what the biomedical community will come up with to bring a sense of closure to the Lacks family.