How evolution made our brains lazy

Pixabay.com

- A new study shows that the brain prefers to expend as little energy as possible.

- Putting forth less effort had advantages for our ancestors.

- Being inactive is not beneficial in modern life and needs addressing.

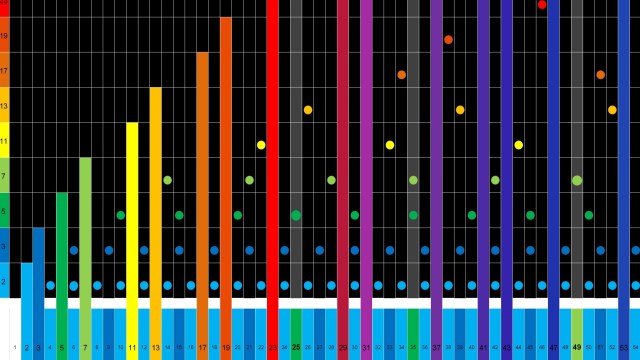

This animation shows the experiment the participants were asked to perform, moving the avatar closer or farther from the image shown.

Credit: UBC Media Relations

Why is it often so hard to get off the couch and go to the gym? While you can certainly point to your lack of will power for the inaction, you can also blame evolution for this predicament. Your brain prefers to minimize effort because that’s how it’s been trained to do it for millennia.

Scientists from the University of Geneva (UNIGE) and the University Hospitals of Geneva (HUG) in Switzerland came to this conclusion after studying the neuron activity of people who had the choice of either engaging in physical activity or doing nothing. The researchers found that it takes much more effort for the brain to escape its general tendency to put forth less effort.

This battle in the mind comes courtesy of our ancestors who aimed to do less to increase the likelihood they would survive. Expending unnecessary energy would have made them more vulnerable to predators or environmental factors. Conserving energy was helpful when competing against rivals, fighting, hunting for prey, and searching for food. Living in modern societies does not require this approach, and yet the predilection of our brains to work less persists.

To gain a better understanding, the scientists based their hypothesis on “the physical activity paradox.” You’ve experienced it if you’ve ever done something like buying a membership to a gym that you attend with less frequency each passing week. This happens when the conflict between your reason-based knowledge (going to the gym is good for my health) runs into the automatic system based on affect, which is, in this case, all the hurt and tiredness you expect to get out of the physical activity. The result is often paralysis—you remain sedentary.

To delve deeper into what is taking place at the neuronal level, the researchers studied the brain activity of 29 people who desired to be more active in their everyday lives but had a hard time doing so. The subjects were made to choose between physical activity or inactivity as the researchers observed their brains using an electroencephalograph (EEG) with 64 electrodes.

The research team was headed by Boris Cheval from the Faculty of Medicine at UNIGE and HUG and Matthieu Boisgontier from Leuven University, Belgium, and the University of British Columbia, Canada.

Cheval explained how the experiment, where subjects controlled an online avatar, was carried out:

We made participants play the “manikin task,” which involved steering a dummy towards images representing a physical activity and subsequently moving it away from images portraying sedentary behaviour […] They were then asked to perform the reverse action.

The scientists looked at how long it took the participants to get near the sedentary image versus avoiding it and found that it took the subjects 32 milliseconds less to move away from the less active image. Cheval called this result “considerable for a task like this.” While such an outcome didn’t correspond to their theory of the physical activity paradox at first glance, it actually ended up confirming it.

It turned out that the reason for why the participants moved their avatar away from images of physical inactivity and towards active pictures more quickly is because avoiding lazy images forced their brains to work harder. That’s due to the fact that the participants wanted to engage in physical activity even if they weren’t doing so. Choosing more active images was actually easier to do. As such, the EEG scans suggested that their brains were essentially hardwired towards laziness.

Matthieu Boisgontier explained why evolution preferred the easy way out:

Conserving energy has been essential for humans’ survival, as it allowed us to be more efficient in searching for food and shelter, competing for sexual partners, and avoiding predators. […] The failure of public policies to counteract the pandemic of physical inactivity may be due to brain processes that have been developed and reinforced across evolution.

He thinks one big takeaway from the study is that the brain has to work hard to avoid physical activity. The team’s research will next focus on whether the brain can be re-trained.

Check out the new study, published in the journal Neuropsychologia,here.