40 Ways to Carve Up England

On 18 September, Scotland voted to stay in the UK by 55% to 45%: a wider margin than most expected, but still close enough to warrant the constitutional re-think promised by Westminster in the run-up to the referendum.

This result will finally require an answer to the famous West Lothian Question (1): With certain matters devolved to separately elected assemblies in Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales, why should Members of Parliament (MPs) elected in those countries to sit in the House of Commons be able to vote on matters that affect only England?

The easy answer is of course that they shouldn’t; the difficult one is how to solve that democratic paradox. One solution could be to exclude Northern Irish, Scottish and Welsh MPs from debates and votes pertaining to English matters only. Another would be to keep the vote open, but to require England-only legislation to get a majority of English MPs behind it. Either solution would create two classes of MPs – hardly an elegant outcome, let alone a more democratic one.

A third option would be to create an English Parliament, provide it with similar powers as the other three assemblies, and leave residual ‘federal’ matters to the Westminster Parliament.To give such an assembly a fresh start, it should perhaps convene outside of London – maybe in Winchester, the ancient English capital, or in either Meriden or Fenny Drayton, two villages east of Birmingham disputing each other’s claim to be the geographical centre of England.

While this would satisfy those who feel that England itself is the least-recognised, longest-suffering colony of the British Empire, the result would be a bit lopsided. England’s 53 million inhabitants represent 83% of the United Kingdom’s population. Placing its representative body on a par with the Welsh Assembly, the Scottish Parliament and the Northern Irish Assembly would create a constitutional imbalance that would make either the English or the three smaller nations very unhappy (and quite possibly all four of them).

This could be solved by devolving central powers to English regions rather than to England as a whole. That would not just be mathematically opportune. Regionalism is a strong force in England. The attachment to city, county or region often is stronger and more tangible than the more abstract notion of nation. The economic situation is also highly divergent regionally.

But how would you carve up England? Alasdair Gunn – he of the equipopulous EU map (see #668) – explores two avenues of Anglo-fragmentation. One is to transpose the administrative units of other countries on England. The other is to imagine existing, often fairly random subdivisions hardening into political borders after power devolves down from Westminster.

Often, the administrative divisions of foreign countries are mentioned to give examples of what a devolved England might look like. However, few plans for devolution give detail on what these divisions would look like, writes Mr. Gunn in the legend of this collection of maps called If England were…

Each map shows England, subdivided into ‘foreign’ units of government of approximately equal population. The maps are arranged left to right, top to bottom.

England would be the equivalent of two Indian states (averaging 26 million each), or three Bangladeshi divisions (app. 18 million each). Although Sikkim, the smallest of India’s 29 states, has less than a million inhabitants and 8 others have less than 10 million, its largest, Uttar Pradesh, has 200 million. Two other states – Maharashtra and Bihar – have over 100 million inhabitants. Dhaka is the most populous of Bangladesh’s 7 divisions, numbering 48 million. The central coastal division of Barisal has less than 9 million.

The average administrative units of Brazil, the US and South America are fairly equipopulous – between 5.8 and 7.5 million inhabitants – with England corresponding to 7 Brazilian states, 8 American ones, or 9 South African provinces. Of course, the actual size of these units varies widely: Sao Paulo (44 million) is almost 100 times more populous than the 27th-ranking Brazilian state, Roraima (less than 0.5 million).

England would be equivalent to 10 German Länder (5.3 million each), 14 Australian states (3.8 million) or 16 Canadian provinces (3.3 million). That would be almost triple the number of states of Australia itself (24 million, 5 states), and considerably more provinces than Canada (36 million, 10 provinces).

Italian regions, Japanese prefectures and Polish voivodeships generally have pretty small circumscriptions, with England the equivalent to 18 regioni (of about 3 million each; Italy itself has 20), 19 todōfuken (circa 2.75 million each; Japan has 45), or 22 województwa (about 2.4 million each; Poland itself only has 16).

Curiously, Russian circumscriptions are even smaller – most are large in area, but thinly populated. England could fit in 30 Russian federal subjects (each counting 1.75 million inhabitants). But Tanzania’s administrative divisions are even closer to its citizens. A Tanzanian region on average contains no more than 1.5 million people. Tanzania itself (46 million) counts 30. England would contain 35 Tanzania-sized regions.

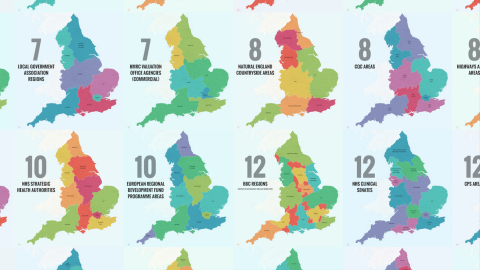

Under the title Tortured Geography, Mr. Gunn proposes 27 more ways to carve up England: The administrative boundaries used by government departments, quangos (2) and other public sector authorities vary wildly, with the same names often referring to very different areas.

There is indeed very little overlap between the country’s three environment agency regions, 4 public health regions, 4 HMRC (3) valuation office agencies, 5 Arts Council regions, 6 Homes & Communities Agency regions or 6 Forestry Commission areas – and that’s just comparing the smallest numbers of subdivisions.

The same place could be in the North & East for one agency, in the East for another, and in the Midlands for a third. Even the most obviously standalone unit, Metropolitan London, is separate only half of the time, and otherwise attached to three different regions.The smallest set of subdivision are the counties, but even these are not confusion-free.

There are, in fact, three different types of counties, only two of which are shown here. England’s historical counties, first established in Saxon times, officially haven’t been abolished, but on most maps they’ve been replaced by either the administrative counties (as introduced by the 1972 Local Government Act) or the ceremonial counties (as defined by the 1997 Lieutenancy Act).

Some historical counties have disappeared off the map entirely. Middlesex, for instance, has been subsumed by Greater London and clings to life as a post code reference and in the names of a university and a cricket club, among others (see also #605).

And even if the name survives, the administrative and/or ceremonial county may have little overlap with the historical one. The continued confusion between these three types of county means that some places can belong to two or even three different counties, depending on which definition is used.

Administrative counties date from the 19th century but were reorganised by the 1972 Act. They reflect the altered demographic reality, re-dividing the ancient counties into local government areas more adapted to modern times and often taking non-historical names and shapes. Quite a few of these counties have already been renamed or reshaped.

The 1997 Act provided for the appointment of lord-lieutenants (i.e. the Queen’s regional representatives) to what were consequently called ceremonial counties – the basis for which in most cases are the unaltered (but sometimes conjoined) administrative counties of the 1972 act. The ceremonial county of Bedfordshire, for example, also includes the administrative county of Luton.

So – what will be the face of post-West Lothian England? Will economics be the deciding factor, and will it look like the map of the 39 LEPs (4)? Or perhaps the institutional factor will decide, and it will resemble the 7 local government association regions. God forbid it should come out as the 10 European Regional Development Fund Programme areas.

Perhaps the smartest move of all might be to add another configuration to the already saturated mix and in a carefully choreographed confusion of change ensure that everything stays exactly as it was.

Images reproduced with kind permission from Alasdair Gunn. See them in their original context on his Deviant Art page.

_______________

Strange Maps #683

[1] So called because it was first raised in 1977 by Tam Dalyell, Member of Parliament for West Lothian, a constituency in Scotland.

[2] A quasi-autonomous non-governmental organisation, which exercises certain powers that have been devolved to it from central government.

[3] Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs, a.k.a. the taxman.

[4] Local Enterprise Partnerships, which a few years ago replaced the Regional Development Authorities.