Three maps remind us of the horror of the Vietnam War

- Like most armed conflicts once they are over, the Vietnam War is fading fast from memory.

- One map reopens the door to a particularly horrific aspect of the Vietnam War: carpet bombing.

- A second map depicts the spraying of various herbicides, and a third depicts U.S. bases named after sweethearts and Nazi strongholds (among other things).

Wars transform nations. Then they end, and as their veterans die, they fade from living memory into history. That is now happening to the Vietnam War, the conflict that dominated both America’s foreign policy and its domestic politics for much of the 1960s and 70s.

Two million Vietnam vets left

Losing the last living link to a war is an important moment in the life of a nation. The death in 1956 of Albert Woolson (106), the last undisputed veteran of the Civil War, was significant enough to be acknowledged by President Eisenhower himself. For Vietnam, the “Woolson moment” is still far off. Of the 2.7 million Americans who served in Vietnam, just under two million* are still alive. But as many are now in their late 70s, their numbers will start to decline rapidly.

For most other Americans, “Vietnam” is ancient history. Heck, even Rambo is 40 years old. The nearest intimation anybody under 50 has of what the war must have felt like, came last year, with the chaotic U.S. evacuation of Kabul. As some with long memories said, it was so eerily reminiscent of the Fall of Saigon in 1975.

But mostly, the Vietnam War has fallen off the radar. Perhaps, this is not so surprising. The martial appetite of those vast legions of armchair generals is sated by an endless stream of content about World War II. As for Vietnam: Communism, which Americans went there to stop from spreading, is no longer a geopolitical threat. Vietnam itself is now an exotic holiday destination for Americans, even a potential ally against China.

Yet there are still doors in time that open directly from here and now into the horror of what the Vietnamese call “the American War.” Pictures, mainly — of that Buddhist monk, self-immolating in anti-war protest, or of that girl, naked and crying because of the napalm that flattened her village and burned her skin.

A carpet bombing map of Vietnam

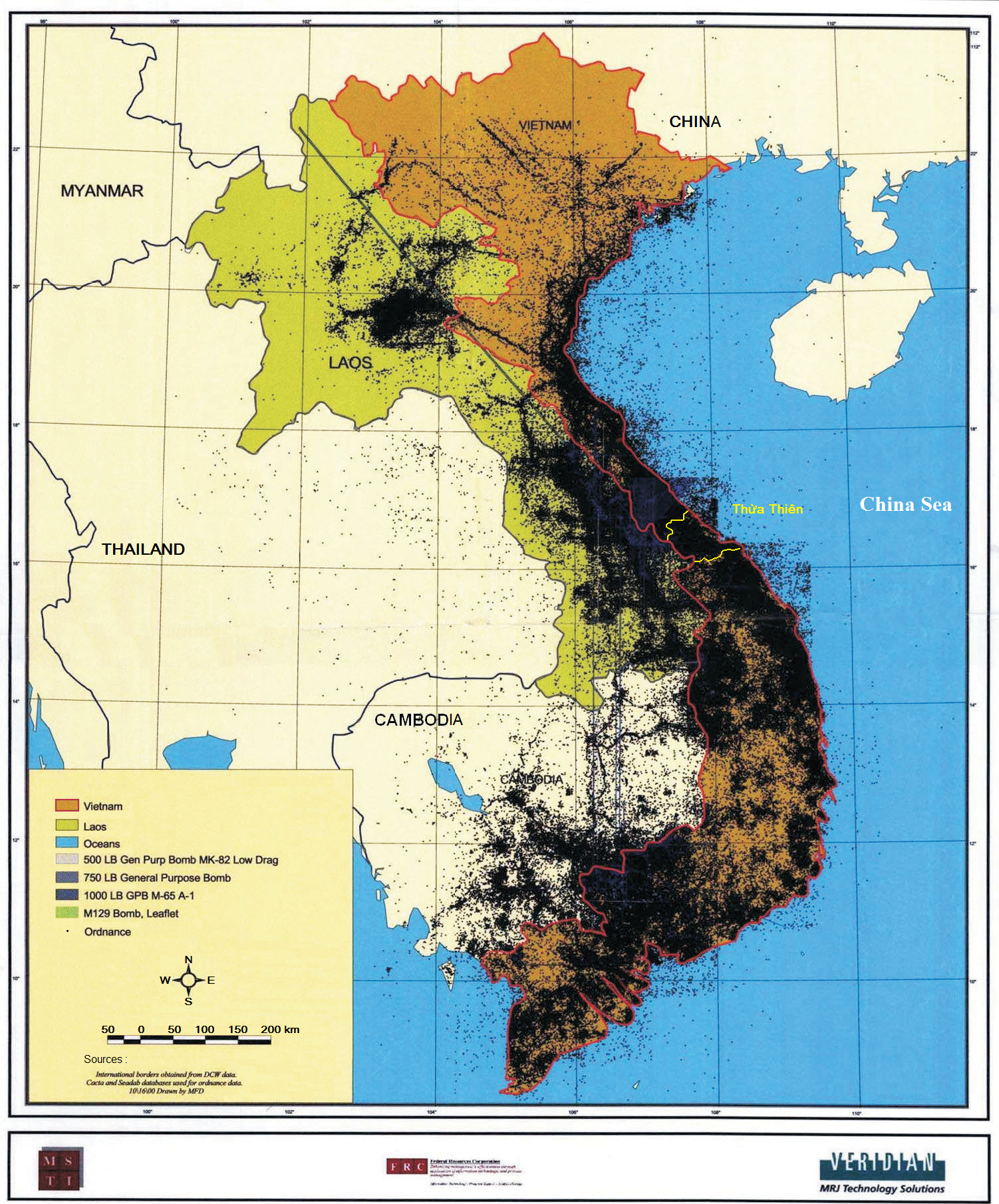

But there are also maps. At a single glance, the following map brings home one of the most horrific aspects of the war: the carpet bombing of Vietnam by the U.S.

Each pinprick symbolizes the dropping of ordnance between 1965 and 1975. A few things strike the unprepared observer.

First, the map does more than merely point out where those bombs fell. By the sheer mass of dots swarming across the map, in many places congealing into broad swathes of sheer black, the effect is almost as if we’re observing some kind of medical malignancy, perhaps an X-ray of a limb being destroyed by cancer.

Second, the carpet of bombs doesn’t quite cover the entire country. Large parts of North Vietnam are relatively bomb-free, possibly because of limited bomber range, effective anti-aircraft deterrent, or both. In those lightly-bombed areas, it is easier to recognize the roads and paths that were the target of much of the raids, also further south. Smaller sections of the South are also relatively bomb-free.

Third, the bombing didn’t stop at the borders of Vietnam. America’s enemies found alternative routes and hideouts outside the country, and America’s bombs went to find them there. Large parts of Laos and Cambodia, Vietnam’s neighbors to the west, were also bombed to smithereens.

Bombing Vietnam — and its neighbors

Then, if you look closely, you see some bombs were dropped well outside the main theater of operations: quite a few on Thailand, a single drop on Myanmar and more than a handful on China. Really? That seems rather unlikely, because it would have been rather dangerous. China was an ally of North Vietnam, but it was not in direct military conflict with the U.S. American bombs on China would have risked drawing in the Chinese, resulting in a much wider, much bloodier war.

And finally, it seems the Americans also made an enemy of the ocean, because they dropped quite a bit of ordnance in the sea, including in two curiously triangular-shaped areas just off the coast of Thừa Thiên Huế province (whose borders are marked in yellow on the map). In the North, it may be assumed that the target was enemy shipping. Elsewhere, and considering the geometrical patterns of the areas of disposal, it may simply be that dropping non-delivered payloads in the sea was somehow easier (or less dangerous) than carrying the explosives back to base.

The map above is taken from At the Heart of the Vietnam War, a monograph about Herbicides, Napalm and Bulldozers Against the A Lưới Mountains, published in 2016 in the Journal of Alpine Research.

As the title suggests, the article’s main topic is the environmental degradation of this area, now in central Vietnam. The aim of the aerial sprayings of herbicide and bombings with napalm by the U.S. and South Vietnamese was not just to hit the enemy but to degrade their environment — to such an extent that they would find it harder to survive and would be easier to spot. The Viet Cong, for their part, used bulldozers to construct roads, in the process also seriously degrading the environment.

As such, the article offers no further context to the map of bombings across Vietnam and its neighboring countries. It does offer a few other maps that, although more regional, illuminate certain aspects of the Vietnam War.

Rain down the “rainbow herbicides”

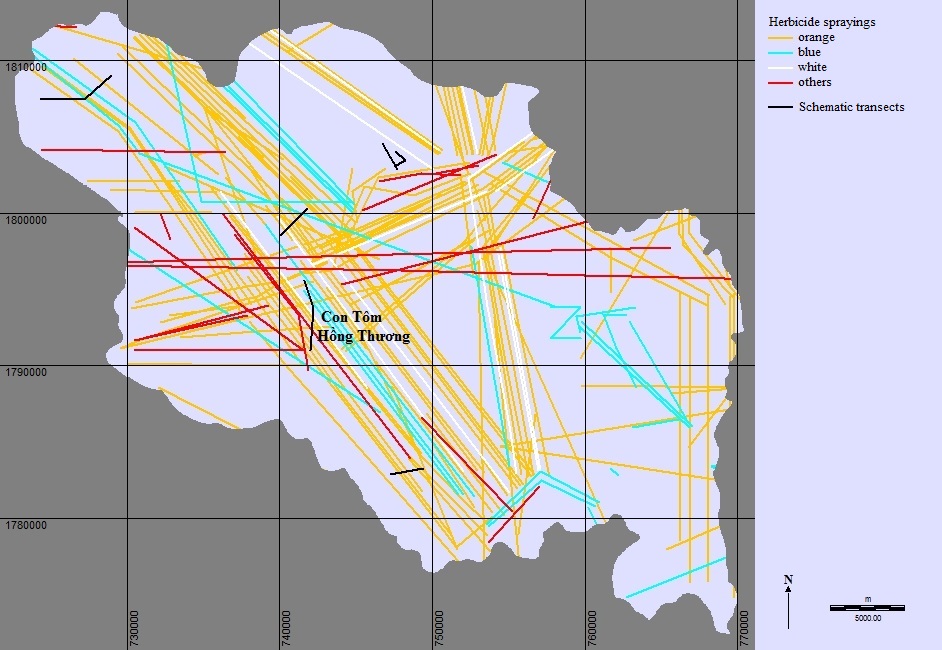

For example, this map shows the dispersal of herbicides across the A Lưới Mountains. Codenamed “Operation Ranch Hand” (1962-1971), the U.S. used herbicides sprayed from the air to destroy both forest canopy and crops, thus denying the enemy cover and food.

Various agents were used, named after colors — hence collectively known as the “rainbow herbicides.” The most infamous was Agent Orange, but as this map shows, there were also Agent Blue and Agent White. Others included Agents Green, Pink, and Purple. In all, nearly 80 million liters were sprayed. The map indicates that the main valley of the A Lưới Mountains was particularly affected. The herbicides are cited as contributors to the untimely death of many Vietnam veterans as well.

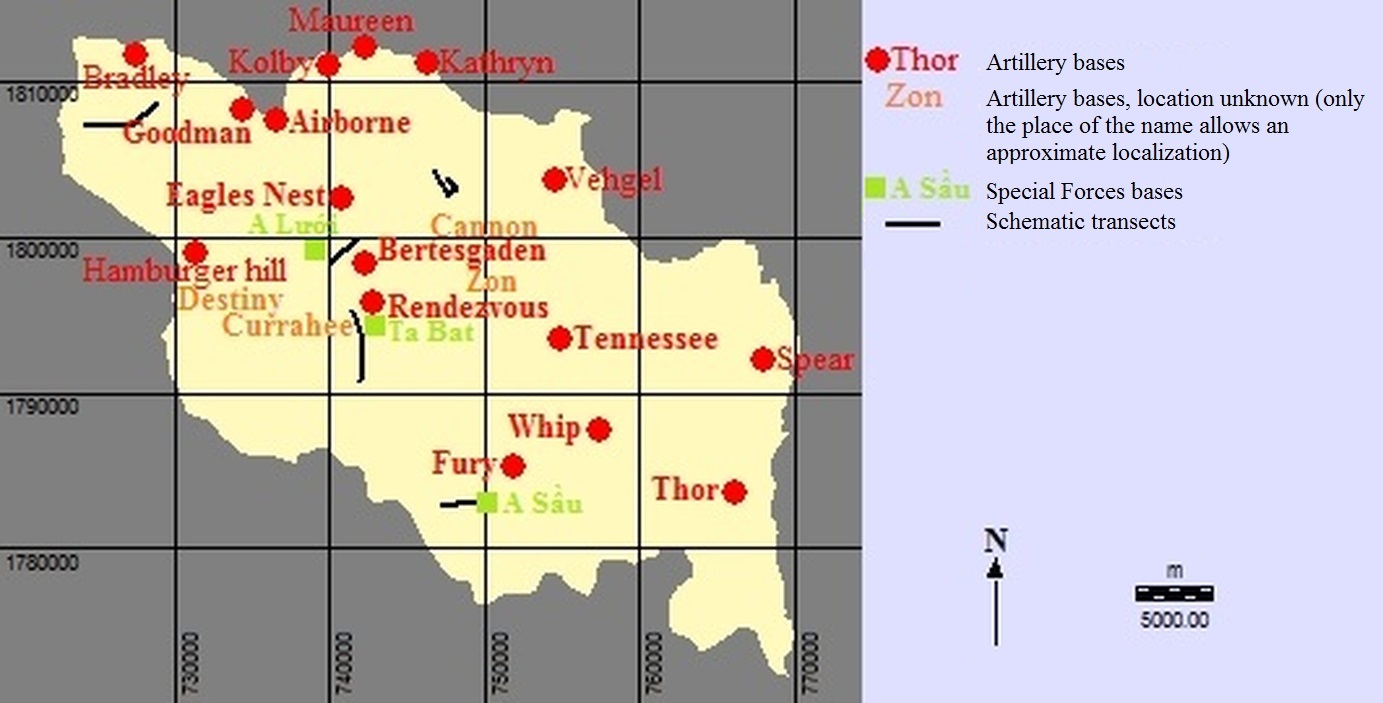

Another map of the same area examines U.S. military bases.

- Squares and names in green denote Special Forces bases — just three of them, all with Vietnamese names.

- Circles and names in red mark the exact locations of artillery bases.

- Names in orange are for artillery bases, the exact locations of which are unknown. Names are placed at their approximate location.

The naming conventions for these bases are quite interesting. Some names refer back to WWII locations in Europe: the Dutch town of Veghel (sic) was an important drop zone during Operation Market Garden. Berchtesgaden (sic) is a town in southern Germany, virtually synonymous with Hitler’s summer residence, which was called Eagle’s Nest — the name of a third base in this area.

From Pork Chop Hill to Hamburger Hill

Other base names seem to refer either to wives or girlfriends (especially first names like Kathryn, etc.), officers relevant to the base (surnames like Goodman), military terms (e.g., Rendezvous), places back home (Tennessee), or just short, aggressive-sounding names like Whip, Spear, or Thor.

One name stands out: Hamburger Hill, ostensibly named after the battle that took place in 1969 at Hill 937. It got its nickname because the soldiers who fought there were supposedly “ground up like hamburger meat.” The 1987 movie of the same name follows fictional members of the 101st Airborne as they prepare for and participate in the battle. The nickname possibly references a similarly-named battle in the Korean War, the Battle of Pork Chop Hill (1953), which (inevitably) also was turned into a movie a few years later.

Year on year, as the legion of America’s Vietnam veterans continues to shrink, the war that once spellbound America and the world will fade further in the collective memory. As these maps prove, the growing distance of time will allow those of us who weren’t around the first time to experience the fresh horror of the uninitiated.

Strange Maps #1131

Got a strange map? Let me know at [email protected].

Follow Strange Maps on Twitter and Facebook.

*Update on February 14, 2022: In a previous version of this article, we stated that as few as 610,000 Vietnam vets were still alive in 2019 (and extrapolating from that rate of attrition, barely half a million today).

This high death rate is an oft-repeated fallacy, resulting from the attribution of mortality figures for all Vietnam-era vets (including the many who never served in Vietnam; a total of about 9.2 million) to the much smaller cohort of actual Vietnam vets (2.7 million). As explained in this 2013 article from the New York Times.

According to that article, about 75% of Vietnam vets were still alive in that year, i.e. just over 2 million. Allowing for an estimated annual decrease of about 1.5%, that would put the total Vietnam vet population at just under 2 million today.

Many thanks to Mr R.J. Del Vecchio for pointing us to that NYT article (which links to a more extensive treatment of the same topic in the VVA Veteran magazine).