Atlas Shrugged off the Wrong Load

Ayn Rand almost called her last novel The Strike, but felt that her magnum opus deserved a more symbolic, less descriptive title. She settled on Atlas Shrugged, as explained by this conversation between two of the book’s characters:

“Mr. Rearden,” said Francisco, his voice solemnly calm, “if you saw Atlas, the giant who holds the world on his shoulders, if you saw that he stood, blood running down his chest, his knees buckling, his arms trembling but still trying to hold the world aloft with the last of his strength, and the greater his effort the heavier the world bore down upon his shoulders—what would you tell him to do?”

“I… don’t know. What… could he do? What would you tell him?”

“To shrug.”

The image of the Titan Atlas shrugging off the weight of the world is directly linked to the book’s central theme. Atlas Shrugged (1957) is the dystopian fable of a future America destroyed by collectivism. Redistributing wealth by taking it from those who create it and giving it to those who don’t is an inherently self-destructive system, Rand claims. In her book, industrialists weighed down by taxation and regulation ‘shrug off’ the increasing burden of government intervention by disappearing from society, which then collapses.

Although it could be classified as science fiction, Atlas Shrugged is also a roman à thèse expounding Rand’s theory of Objectivism – a philosophical system that equates morality with rational self-interest and the good society with an extreme form of capitalism.

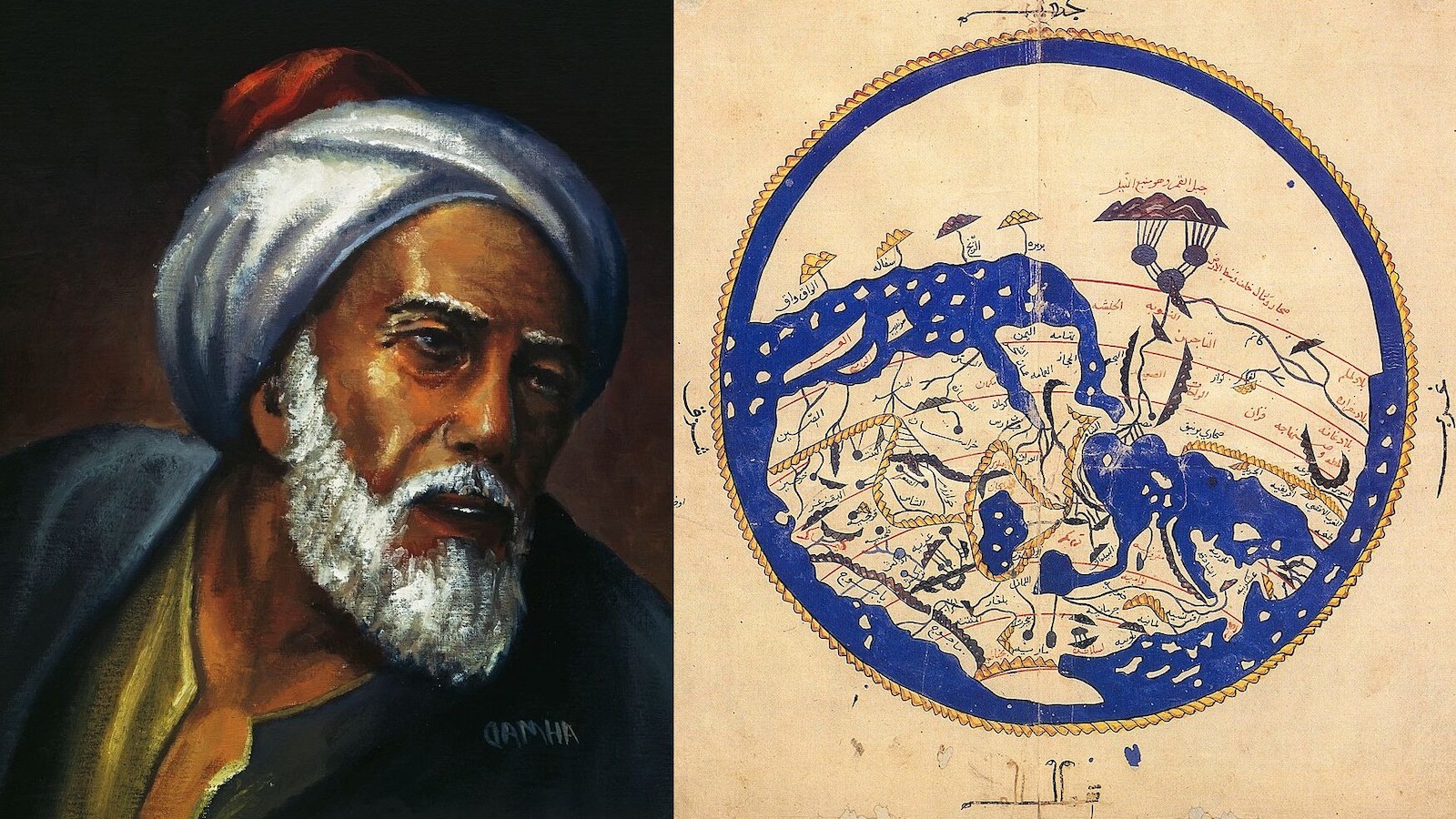

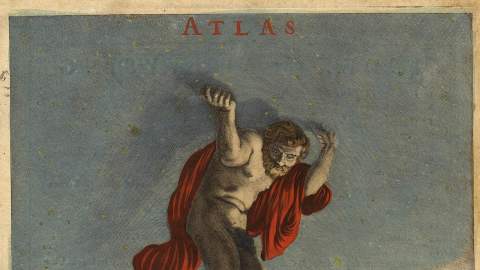

Atlas holding the world aloft, as imagined by Ayn Rand. (Image in the public domain, at Wikimedia Commons)

Atlas Shrugged is the book of books for a significant number of libertarians and conservatives, who have an almost religious reverence for Ayn Rand and her worldview. Alan Greenspan, Chairman of the Federal Reserve from 1987 to 2006, claimed that he was “grateful for the influence she had on my life. I was intellectually limited until I met her.”

But opponents of her philosophy are at least as vocal and as numerous. The late Christopher Hitchens lamented, “I have always found it quaint and rather touching that there is a movement in the U.S. that thinks Americans are not yet selfish enough.” Writer John Rogers quipped that “[t]here are two novels that can change a bookish fourteen-year old’s life: The Lord of the Rings and Atlas Shrugged. One is a childish fantasy that often engenders a lifelong obsession with its unbelievable heroes, leading to an emotionally stunted, socially crippled adulthood, unable to deal with the real world. The other, of course, involves orcs.”

This blog is about maps, and is not concerned with the literary or philosophical merits of Ayn Rand’s work. Yet there is a cartographic connection. The title of her book came to mind when we came across this image of Atlas – standing on the world rather than carrying it, propping up the heavens, not the earth.

From Frederik De Wit, Atlas Standing on Earth, Holding up the Heavens. (Image in the public domain, at Wikimedia Commons)

This Atlas is an anti-version of our standard concept: the Atlas who carries the weight of the world, and is compelled to shrug off that burden by Rand. This Atlas is from the frontispiece of Frederik De Wit’s 150-map Atlas (Amsterdam, ca. 1688). His hands seem to clutch at a low ceiling. He looks like he’s uncomfortably wedged between the North Pole and the celestial dome above him. Is he pushing the sky up, or the world down?

To make the image even weirder, turn it on its head. Now Atlas is down and the world is up, as we imagine they should be. But the planet-lifter is face down, standing on his head. Balancing himself with his hands, he props up the earth with his feet like some circus act, or like Medieval scholars believed their antipodes to walk on the other side of the earth.

An ‘Antipodean’ Atlas.

Who was right, Ayn Rand or Frederik De Wit? Who is this Atlas character anyway? How did his name end up on the cover of all our map books? And what if anything is his relation to Morocco’s Atlas Mountain range?

The word ‘atlas’ now primarily means a systematic collection of maps in book form. The first modern collection of that kind did not yet come with that name. Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (Antwerp, 1570) by Abraham Ortelius translates as ‘Theatre of the World Globe’. A few years later came Speculum Orbis Terrarum (Antwerp, 1578), or ‘Mirror of the World Globe’, by Gerard and Cornelis De Jode.

Had it not been for Mercator, we might today casually ask to pass the theatrum or the speculum when looking to consult a map. His Atlas, sive Cosmographicæ Meditationes de Fabrica Mundi et Fabricati Figura (Duisburg, 1595) set the standard for successive generations of mapmakers and provided them with a new and peculiar name for their collections. But where did Mercator get the name for his ‘Atlas, or Cosmographic Meditations on the Fabric of the World and the Figure of the Fabricked’?

Mercator was the first cartographer to call his collection of maps an Atlas. In the introduction, he explained the title not only by referring to the eponymous figure of Greek mythology, but also linking him – via a convoluted genealogy – to his namesake, a legendary king of Mauritania skilled in astronomy. This King Atlas was credited with inventing the first celestial globe. Although he ruled over parts of present-day Morocco, it’s uncertain whether there is any etymological link between the Atlas Mountains and him. Or the first Atlas, for that matter.

That Atlas was a son of the Titans Iapetus and Asia and a brother of Prometheus. He led the Titans who supported Kronos in his divine war against his son Zeus. When Zeus won, he condemned Atlas to carry the vault of heaven on his shoulders, so Ouranos (heaven) and Gaia (earth) would be unable to produce any more divine offspring to threaten his supremacy.

Literary sources from antiquity confirm that Atlas held up heaven, not earth, although accounts vary on his location and method. In Book I of the Odyssey, Homer (8th century BC) describes the island on which Calypso holds Odysseus captive: “It is an island covered with forest, in the very middle of the sea, and a goddess lives there, daughter of the magician Atlas, who looks after the bottom of the ocean, and carries the great columns that keep heaven and earth asunder.” But there are no pillars and no ocean floor in the Theogony of Hesiod (8th/7th century BC), where “[…] Atlas through hard constraint upholds the wide heaven with unwearying head and arms, standing at the borders of the earth before the clear-voiced Hesperides; for this lot wise Zeus assigned to him.”

That last image comes close to our idea of Atlas balancing the world on his back, making full use of his head and arms. But when and why was earth substituted for heaven? The Greeks generally thought the earth was flat and fixed (see #288 for a representation of the Greek oikoumene) and the universe a sphere that revolved around it. On the furthest sphere were stuck the immovable stars, with seasonally moving stars attached to crystal spheres closer by, and a separate one for each of the wandering bodies of heaven nearest earth – the planets.

But science has moved on, and our conception of the universe has reversed. We now know the earth is a sphere (at least most of us think so, see #437) and the astronomical consensus is that the universe is not. That reversal has taken root in our minds, commuting the sentence of Atlas. No longer labouring under the weight of the heavens, he now merely carries the world on his shoulders.

The Rockefeller Atlas, a (false) symbol for Objectivism. (Image: Rob Young, licensed under Creative Commons 2.0)

So: if you see an Atlas who props up the earth, he’s likely to be modern, but he’s certain to be wrong. The only mythologically correct depiction of the defeated immortal holding aloft a sphere is if that sphere shows stars and constellations instead of continents and oceans. The 15-ft bronze Atlas guarding the entrance to Rockefeller Center on 5th Avenue in New York since 1937 conforms to the original sentence: Atlas holds up a ball made up of bands of metal that represent the movements of heaven.

Which is ironic, as this very statue is so often used to illustrate covers of Atlas Shrugged that it has come to symbolise Ayn Rand’s philosophy itself.

Strange Maps #682

Got a strange map? Let me know at [email protected].