Why Earth’s oceans aren’t all equally salty

- Oceans and seas are too salty to drink from. But exactly how salty are they?

- The global average salt level in surface seawater is about 35 grams (seven teaspoons, give or take) per 1,000 grams of water (about a quart).

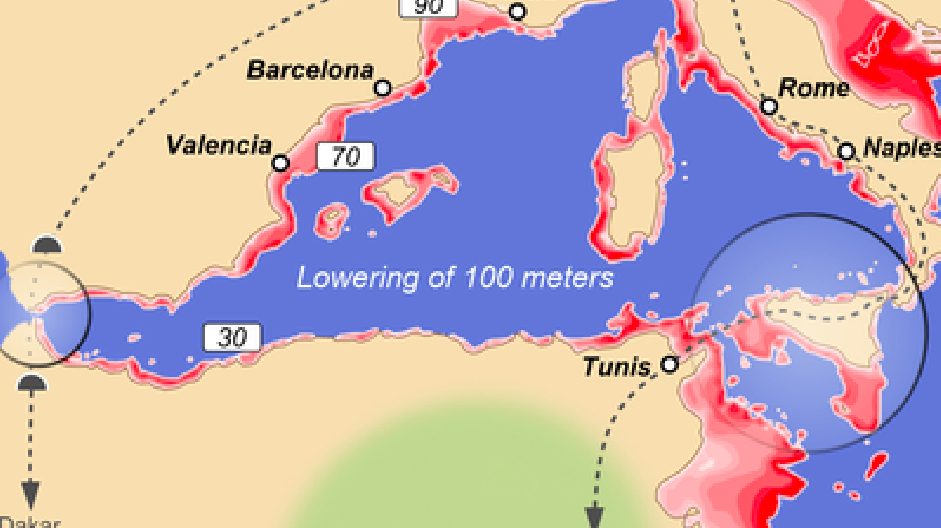

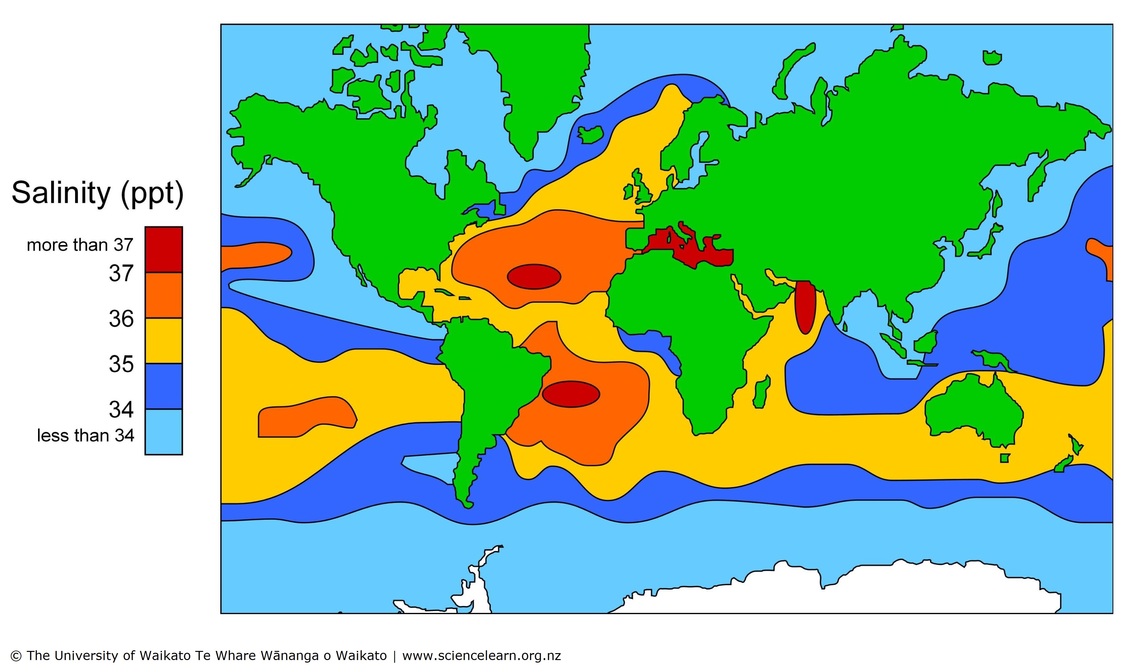

- As this map shows, some seas and oceans are a lot saltier than others.

“Water, water, every where / Nor any drop to drink,” laments the Ancient Mariner. That’s because the ocean surrounding his ship is too salty. Our bodies can’t process the salt in seawater, and drinking it would actually dehydrate you further. You could drink the whole ocean and still be thirsty.

All of Earth’s oceans, and all bodies of water connected to them, are salty — the result of millions of years of mineral runoff carried by rivers to the sea. However, this map shows a considerable and consistent variation in salinity levels across the world’s marine domains.

The Mediterranean Sea is one of the world’s saltiest. One of the least salty is the Baltic Sea.

The global average salt level in surface seawater is about 35 grams (seven teaspoons, give or take) per 1,000 grams of water (about a quart). For short, that’s 35 ppt (parts per thousand).

As shown by the map, salinity increases to 37 ppt and more in large pockets in the North and South Atlantic, in the Mediterranean, and in a northern corner of the Indian Ocean.

It decreases to 34 ppt and less toward the poles, off the west coast of North America, and the coasts of Southeast and East Asia.

Evaporation and fresh water

Why the variation? In the case of higher salinity: evaporation. There are parts of the ocean where hardly any rain falls, and where heat and wind cause lots of water vapor to rise from the sea into the atmosphere. The water that stays behind is saltier as a result.

This is also the case in the Mediterranean, a nearly enclosed body of water subject to lots of sunshine and relatively little rainfall. The eastern Mediterranean has a salinity of about 38 ppt.

In general, the salinity maxima (not just in the Atlantic but also in the Pacific) occur at around 20 degrees latitude north and south, which corresponds to the latitudes of the world’s great deserts, where evaporation also exceeds precipitation.

Conversely, seawater becomes less salty with the addition of fresh water, whether delivered as rain, river water, or — in the polar regions — icebergs. Also, the formation of ice floes in the coldest parts of the world removes more salt from the water.

Consequently, salinity around Antarctica is just below 34 ppt and can go down to 30 ppt in certain parts of the Arctic. The Baltic has a salinity as low as 7 or 8 ppt, because it is fed by hundreds of rivers, and is almost entirely cut off from the (much saltier) high seas.

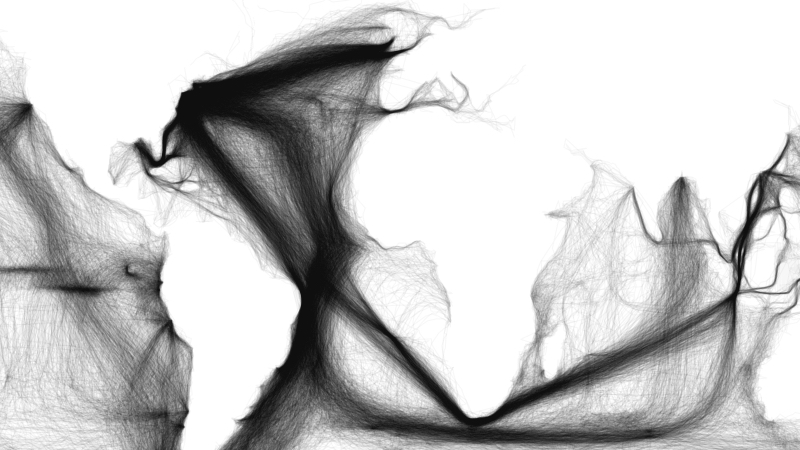

The salinity of the oceans is not just a matter of taste. Saltier water is denser and will sink below less salty and less dense water, creating currents. When it gets colder, that effect is amplified. High-saline, low-temperature water sinks to the bottom of the ocean, where it forms deep and slow underwater rivers.

The saltier deep has a fringe benefit for submarines. A halocline is a layer of water where the level of salinity changes abruptly. That difference doesn’t just affect the density of the water; it also scrambles sonar, giving subs an advantage in their games of hide and seek with other subs.

Strange Maps #1254

Got a strange map? Let me know at [email protected]

Follow Strange Maps on X and Facebook