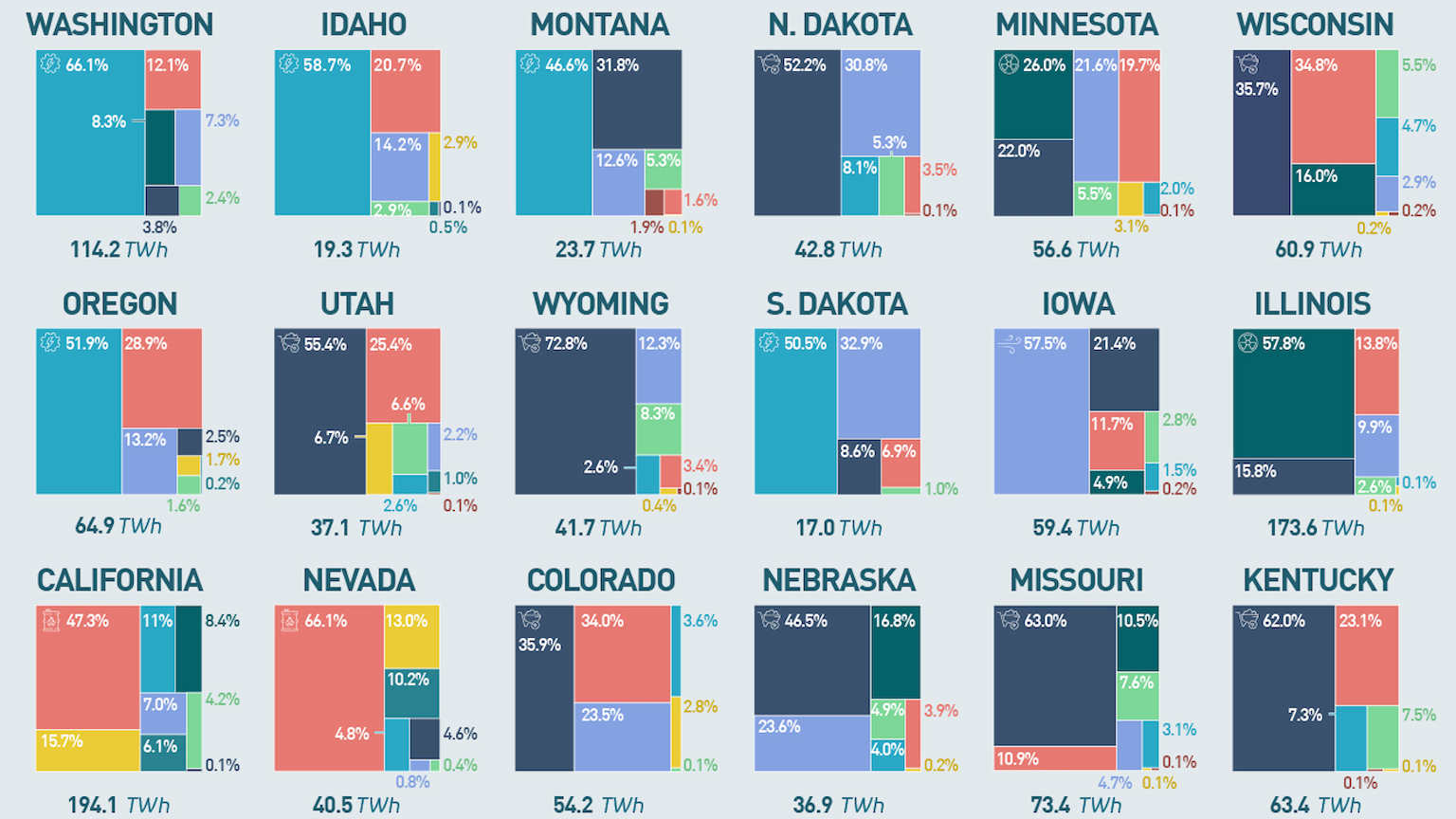

19th-century atlas offers glimpse of North Sea’s fish-rich past

Image: Wellcome Collection. Public domain.

- In little more than a century, fish stocks in the North Sea have declined by 99%.

- For people living today, a grey and exhausted sea is all they know.

- O.T. Olsen’s Atlas of the North Sea’s fish species is a reminder of the richness that once was.

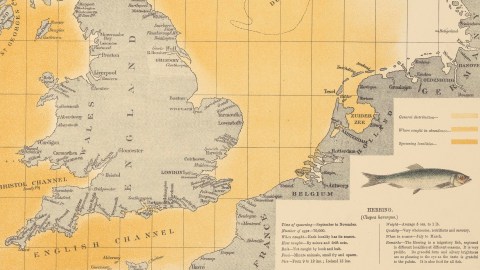

In red, an oyster bank the size of Wales, between the Dogger Bank and the coast of northern Netherlands. Image: Wellcome Collection. Public domain.

Ole T. Olsen’s ‘Piscatorial Atlas’ is a masterclass in data presentation, and it doesn’t half look bad either. As map guru Tim Bryars says: “The late nineteenth century was the heyday of the thematic atlas, but I have rarely seen one quite so specialist or as magnificent.”

But the atlas does more than be clever and look cool. It’s also a window into a world that’s now destroyed and forgotten: one in which the North Sea – the body of water between the British east coast and the European mainland – teemed with life. Published in 1883, the atlas devotes one map each to 40-odd species of fish and crustaceans, describing their habits and habitats, and how and when to catch them. Less than a century and a half later, all are now greatly reduced, and some are functionally extinct in the North Sea.

Each map legend details when the species spawns, when and how they can be caught, what they eat, how much they weigh, and what their qualities are. Anchovy, for example, is “excellent for sauce”.Image: Wellcome Collection. Public domain.

We think of our environment as ‘normal’, but that’s because we don’t know any better – by definition, we weren’t around to experience the ‘normal’ from before we were born. This phenomenon is called Shifting Baseline Syndrome, and it’s no coincidence that this psychological term has found wide currency in fishery science. Because only SBS and the ‘generational blindness’ it implies can explain how the virtual extinction of global fish stocks over the past century took place with such little notice.

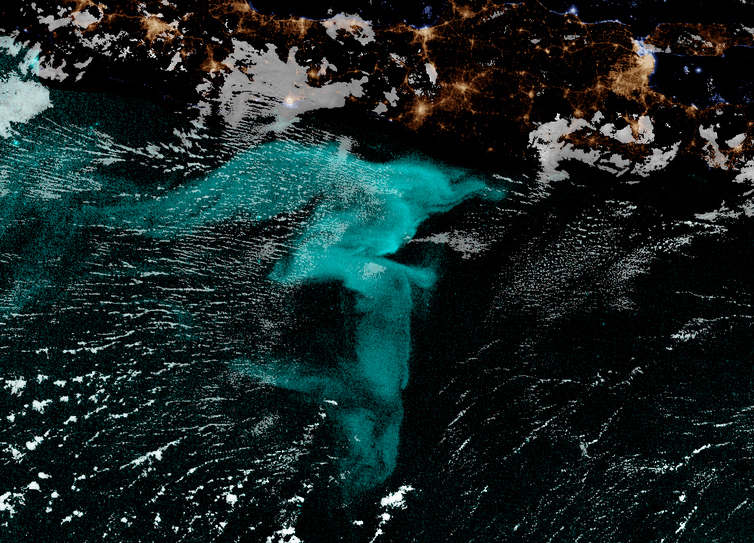

Consider for a moment the North Sea’s waters – grey and soupy today, as everyone thinks they’ve always been. But thronging its seabeds were once so many oysters, each of which can filter up to 200 litres of water each day, that the sea must have been a lot clearer, as well as healthier for other marine species.

The North Sea’s native European oysters (Ostrea edulis) have been a prized delicacy for millennia. They were shipped in quantity all the way to Rome, and tasty enough to be mentioned by Pliny the Elder and Juvenal. In more recent centuries, they were the street food of the urban poor. Back in the 1850s, half a billion oysters were sold each year at Billingsgate fish market in London, harvested from the oyster beds that ringed Britain and Ireland.

“The conger is very voracious, will attack man in the water, is very prolific, and its young furnish a great amount of food for other fish. It is also used for isinglass (a gelatin obtained from fish, used in making jellies, glue, etc. and for fining real ale – Ed).”Image: Wellcome Collection. Public domain.

In particular, Olsen’s atlas shows one giant oyster area bigger than Wales, hemmed in by the Dogger bank and the northern coast of the Netherlands. That patch is now gone. As it turned out, Olsen composed his atlas jut before industrial fishing would start to decimate the marine species of the North Sea.

By the end of the 19th century, the oyster catch started to dwindle, due to overfishing and pollution. By the 1970s, the Pacific rock oyster had to be introduced into the North Sea to satisfy demand. By the 1980s, the European oyster had all but vanished. Heroic efforts are being made to bring back the native oyster, but current stocks are barely 5% of what they were 200 years ago.

Compounding the loss of the oysters themselves is the loss of the reefs they build: these help regulate marine ecosystems, build a habitat for biodiversity – by providing food, nursery grounds and refuge for many fish species. Many of those reefs were destroyed by industrial trawling, which has proved equally devastating for other marine species in the North Sea.

The mackerel was thinly spread across the North Sea, and more numerous to the west, in the Irish Sea and in the Bristol and English Channels.Image: Wellcome Collection. Public domain.

Between 1889 and 2007, a statistical study of historical fish catch data shows, fish landings from bottom trawl catches in England and Wales declined by a jaw-dropping 94%. In other words: the modern fish stock in the North Sea is just one-seventeenth the size it was in the late Victorian era. That implies “an extraordinary decline in (…) fish and a profound reorganization of seabed ecosystems”, the study says. No prizes if you guess what caused the decline: more than a century of industrialised trawling.

This figure applies to so-called ‘demersal’ (or bottom-dwelling) species like cod, plaice, haddock and halibut. In particular, haddock had fallen to less than 1% of its former volume, halibut to one-fifth of 1%. Another study suggests that the current biomass of large fish in the North Sea is up to 99.2% lower than if no fishing had occurred.

Bottom-trawling is the main method of catching bottom-living fish today. First attested in the 14th century, the process was industrialised from the late 19th century, first with the advent steam trawlers, and greatly expanded in the 20th century. Already in 1885, the UK government examined claims that industrialised fishing depleted stocks and damaged habitats. But conservation efforts came to nothing, among others by the absence of hard data.

Shrimp fishing grounds all hug the coast – but are largely absent from the Norwegian and Danish coasts.Image: Wellcome Collection. Public domain.

In fact, the increasingly effective methods of industrial fishing have masked the negative effects they have had on fish stocks. According to the study cited above, the recent history of fishery in England and Wales can be divided into four phases:

- From 1889 to the onset of WWI: the fishery fleet is converted from sail to steam. Fishing is rapidly industrialised and intensified. Stocks start to decline, but this is compensated by massive expansion of the catch areas.

- The interbellum (1919-1939): In a second wave of expansion, fishing vessels go as far away as the Arctic and West Africa, managing to increase catches until the late 1950s.

- From the end of WWII to the early 1980s: fast-declining fish stocks in the North Sea and beyond. As a protective measure, Iceland and other countries declare Exclusive Economic Zones of 50, then 200 miles.

- From 1983: the UK (and Ireland) join the European Economic Community, and must adhere to the Common Fisheries Policy.

The CFP is a compromise, forcing EU member states to adhere to fish quotas in order to allow the stocks to recover from overfishing. However, it is estimated that quotas have always been up to 35% higher than the levels advised by scientists as sustainable. In order to minimise displeasure of the fishing industry, the CFP has prioritised maintaining catch levels over maintaining stock levels.

“Very wholesome, nutritious and savoury,” the herring is “as pleasing to the eye as the taste is grateful to the palate. It is also food for all fish.”Image: Wellcome Collection. Public domain.

As a result, it is estimated that stocks of demersal fish in the North Sea have declined by 42% since the early 1980s. “In many cases, today’s fisheries are sustained by populations of species that should be considered commercially extinct,” says the study. The end of the line has been a long time coming:

- In 1889, Britain’s sail-powered fishing fleet landed twice as many fish as today’s highly sophisticated vessels.

- In 1910, British fishermen landed four times as many fish as they do today.

- The peak year for North Sea fishing was 1938, when 5.4 times more fish were landed in the UK than today.

- Mackerel fishing ceased in the 1970s due to overfishing. The same could soon happen for herring, cod and plaice.

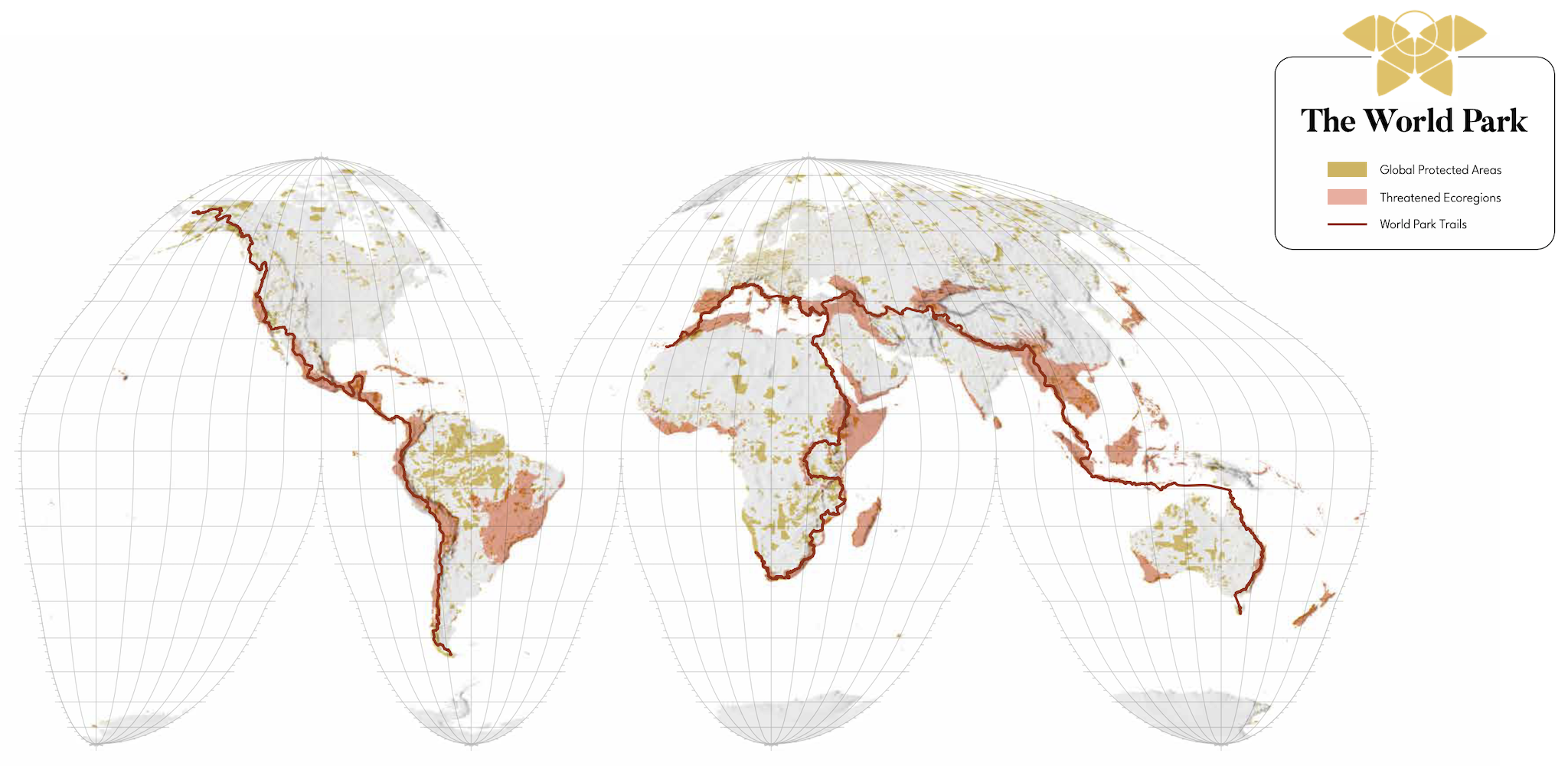

For the Leave campaign in Britain’s 2016 Brexit referendum, the British fishing industry and its perceived suffering at the hands of EU bureaucracy was a major issue. Brexit meant ‘taking back control’ of British waters and the fish that swim in them, doing away with the limiting quotas imposed by Brussels.

But the baseline has shifted; the piscatorial richness that informed Olsen’s atlas and which once filled the North Sea has gone. And duelling with the European Union over those dwindling fish stocks feels a bit like what Borges said about the absurdity of the Falklands War: “a fight between two bald men over a comb.”

See every page of Olsen’s ‘Piscatorial Atlas’ in great detail here at the Wellcome Collection.

Strange Maps #1021

Got a strange map? Let me know at [email protected].