The Fabulous (and Indeed False) Mountains of Kong

Nobody has ever climbed the fabled Mountains of Kong. The snow-capped sierra, its foothills reputedly glistening with gold, features on over 40 maps of West Africa. The chain of mountains is generally shown running along the 10th parallel from Tambacounda (today in eastern Senegal), seamlessly connecting to the Mountains of the Moon in Central Africa. But neither range is real. The only thing they both prove is that the geographic imagination abhors the vacuum of blank spaces on the map.

Though there are no Mountains, there is a Kong. Currently a minor town in northern Ivory Coast, in previous centuries it was a major trading hub between the desert north (producing salt and cloth) and the forest south (furnishing slaves and gold). For most of the 18th and 19th centuries, Kong was the capital of a vast inland empire. In 1898, this Kong Empire fell to the French, who included it in Afrique occidentale française, the federation of eight French colonies that collapsed in 1960, when decolonisation swept over the entire African continent.

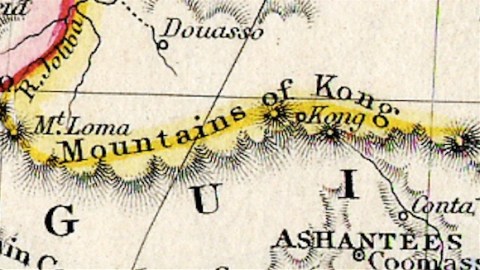

First appearance of the Mountains of Kong, in James Rennell’s map of North Africa (1798). Image taken here at London’s fabulous Altea Gallery.

By the late 19th century, the Mountains of Kong had already been disproved. They had “existed” for less than a century. The very first time they were mentioned was in 1798, when James Rennell included them on a map of the region. The English cartographer based himself on reports by Scottish explorer Mungo Park, expanding and repositioning hints of mountains to support his own theory on the course of the Niger River. A chain of mountains hundreds of miles long would explain the watershed between the Niger basin to the north and the Gulf of Guinea in the south.

As the Mountains of Kong grew in the imagination of successive cartographers, they were deemed an impassable obstacle to commerce and communication between the coast and the interior of West Africa; which is ironic, considering the fact that Kong itself was a trading hub between both regions.

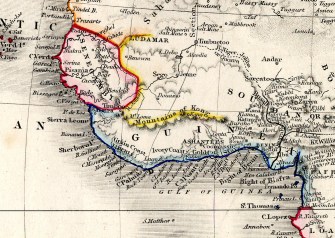

Despite their utter fictionality, the Mountains of Kong remained on maps of Africa throughout the entire 19th century. Their first widespread appearance was in Aaron Arrowsmith’s Africa atlas (London, 1802). The 1833 edition of Abbé Gaultier’s Géographie, in France, mentions the Mountains of Kong as “one of the eight main mountain chains in Africa, separating Nigritia (1) from Guinea, and a continuation of the Mountains of Sierra Leone, in Senegambia.”

View of the Mountains of Kong, from Mitchell’s School and Family Geography atlas (Philadelphia, 1839). Image found here, uploaded to Flickr by Michael L. Dorn.

In 1880, the fourth edition of Meyer’s Conversation Guide, in Germany, describes the Mountains of Kong as “unexplored mountains, extending north of the coast of Upper Guinea over a length of 800 to 1,000 km between the seventh and ninth degrees latitude North, until longitude 1° West of Greenwich.” The city of Kong, “unvisited by any European, but reported by natives to be the biggest market town of the region, and the origin of cotton sought after throughout the entire Soudan,” was supposed to be at the range’s western extremity.

Even Jules Verne mentions the Mountains of Kong. In chapter 12 of Robur the Conqueror (1886), he mentioned: “In the morning of the 11th the Albatross crossed the mountains of northern Guinea, between the Sudan and the gulf which bears their name. On the horizon was the confused outline of the Kong mountains in the kingdom of Dahomey.”

On 20 February 1888, Louis-Gustave Binger, exploring the course of the Niger River, was finally able to ascertain just how confused the outline of that mountain range was. On that day, the French officer-explorer reached the town of Kong, finding mosques instead of mountains, thus finally disproving one of geography’s more persistent phantoms.

Mountains of Kong from Milner’s Atlas (1850); Image taken here from Wikimedia Commons.

In their article on the Mountains of Kong in the Journal of African History (2), Thomas J. Bassett and Philip W. Porter write how “the enduring depiction of the Kong Mountains throughout the 19th century illustrates the authoritative power of maps. This authority is based on the public’s belief that cartographers are guided by an ethic of accuracy and are applying scientific procedures in mapmaking. Despite doubts about the existence of this mountain chain, the ‘extraordinary authority’ of maps helped to perpetuate an erroneous spatial image of West Africa until Binger’s famous expedition in the late 1880s.”

Even after Binger, this particular map ghost has proven hard to dispel. The Mountains of Kong had a final farewell appearance in Trampler’s Mittelschulatlas (Vienna, 1905). But a report on a solar eclipse in 1908 still stated that it “will terminate on the Mountains of Kong, in Upper Guinea”. In 1928, John Bartholomew’s Oxford Advanced Atlas, although not showing the Kong Mountains on the map, still listed them in its index (at 8°40′ N, 5°0′ W). Just over 20 years ago, they crept into Goode’s World Atlas (1995).

Many thanks to Ezra Buonopane for suggesting the Mountains of Kong.

_________________

Strange Maps #733

Seen a strange map? Let us know at [email protected].

(1) In French: Nigritie, in English: Nigritia, or Negroland. An archaic geographic term describing the thinly explored inland of West Africa. Possibly a direct translation of the Arabic bilad as-Sudan,‘the land of the blacks’. Under French colonial rule, the current independent nation of Mali was for some time known as le Soudan français.

(2) ‘From the Best Authorities’: The Mountains of Kong in the Cartography of West Africa. The Journal of African History, Volume 32, Issue 03, November 1991, pp. 367-413. More on that article here.