Columbus was neither the first nor the nicest. But his voyage was the most important

- Can you imagine America without horses or apples? Europe without potatoes or chocolate?

- That’s what the world was like before the “Columbian Exchange,” an event initiated by Christopher Columbus.

- While Columbus wasn’t the first (or nicest) discoverer of the Americas, he is the most consequential because of the Exchange.

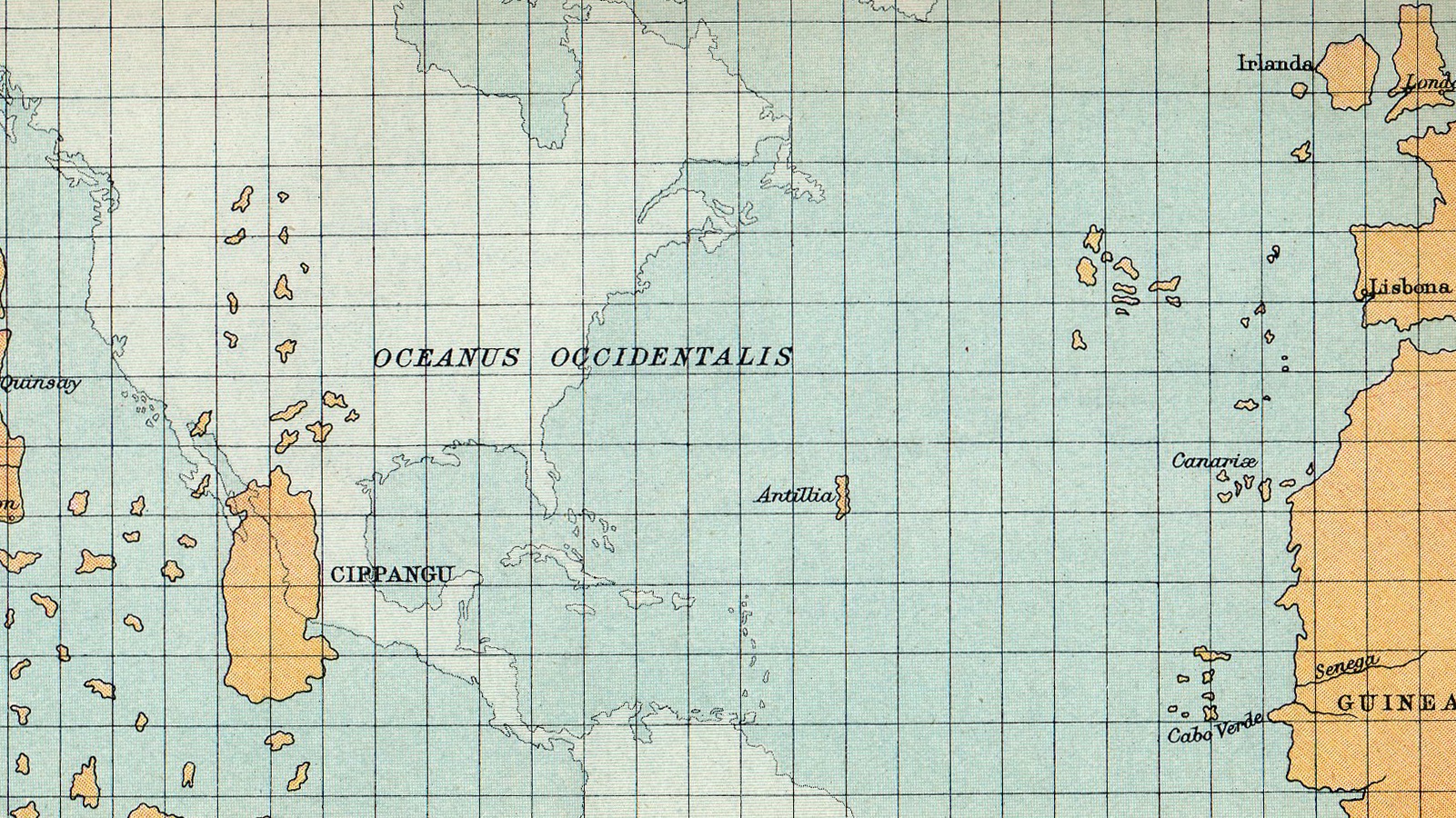

One of my favorite childhood books was The Discovery of America Before Columbus. Extrapolating from scant archaeological and ethnographic evidence and building on oblique references found in ancient myths and manuscripts, its author postulated a host of pre-Columbian visitors to the Americas: not just Vikings (whose visits have indeed been attested) but also the Irish, Welsh, Etruscans, Romans, Africans, Japanese, and Chinese.

The book combined the heft of history with the thrill of science fiction, launching a bunch of counterfactuals at the supposedly solid sandcastle that is the world as we know it. I reread it until its pages came unstuck. Ultimately, however, none of those possible “discoveries” matters as much as the one made by Christopher Columbus in 1492.

This is not because Columbus was the first and certainly not because he was a lovable character. He was neither. But the sailor from Genoa did do something unprecedented that changed the world forever: He added a whole continent to the “known world.”

Adding a whole continent to the known world

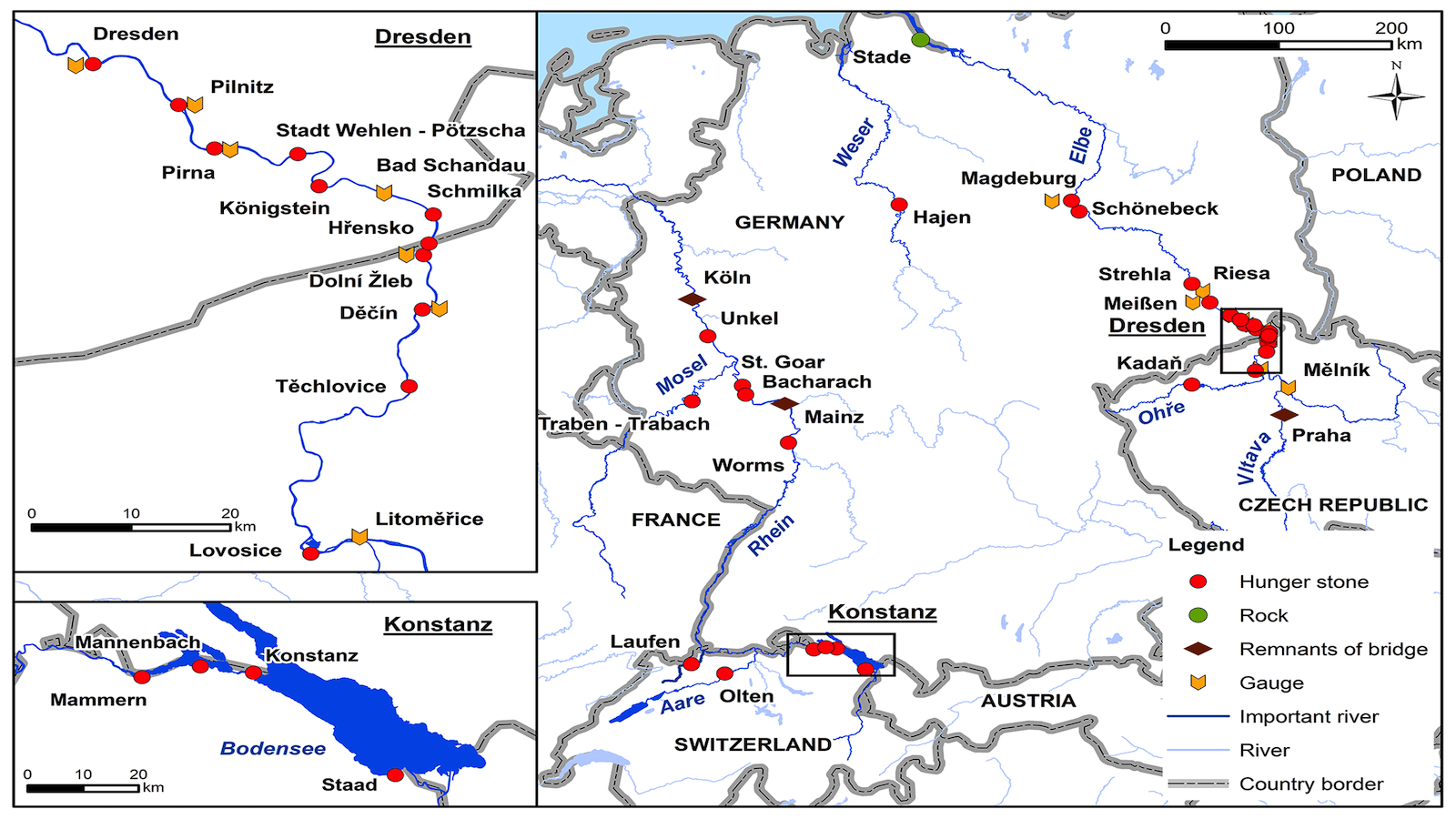

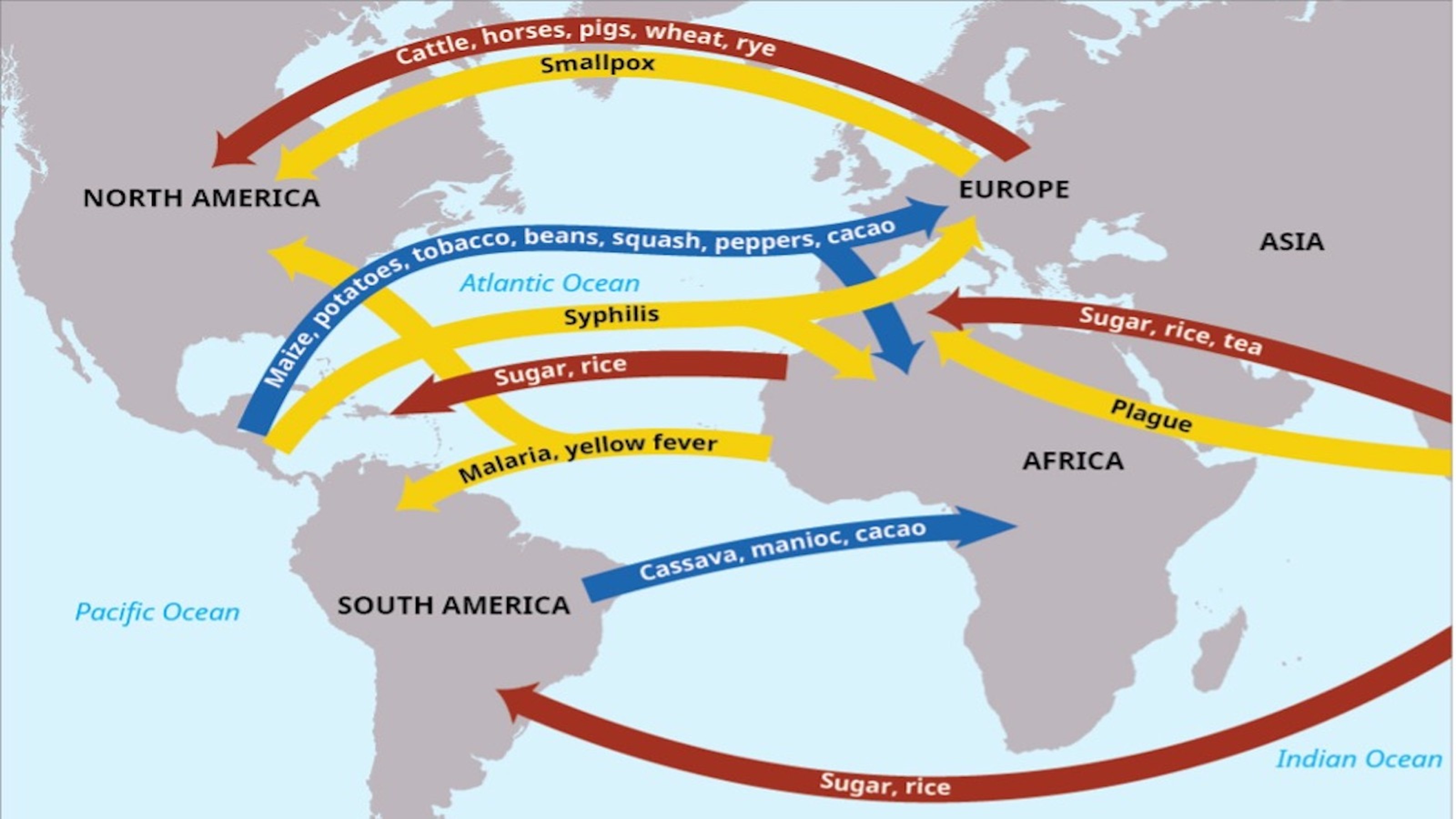

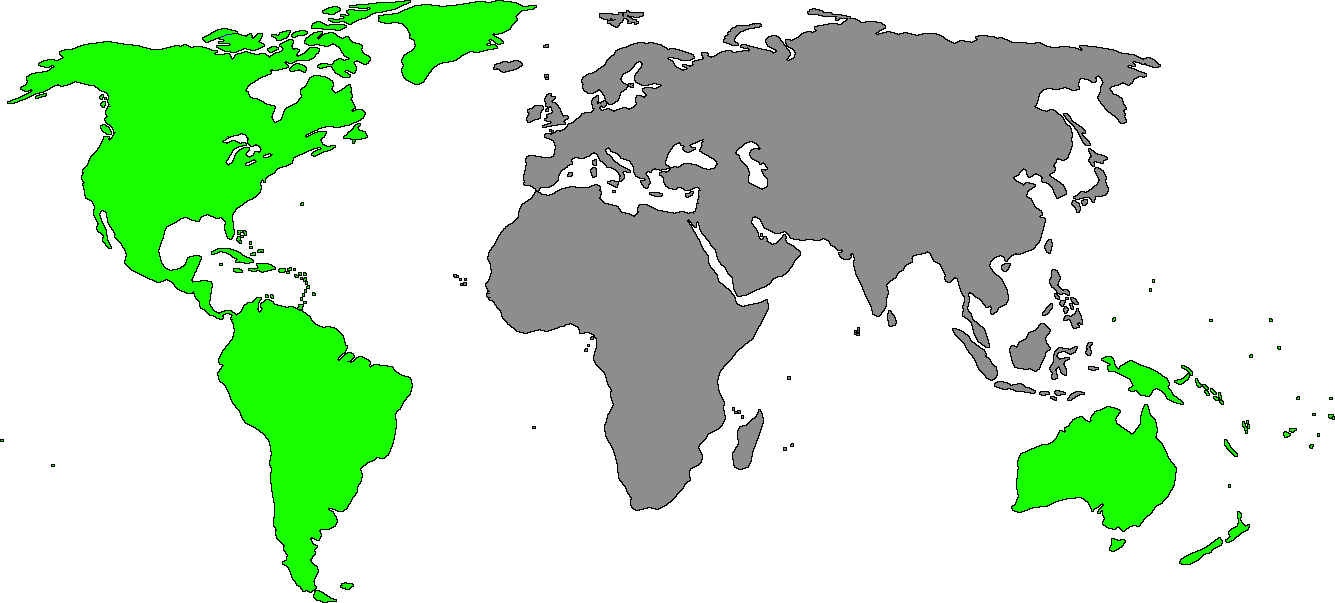

Before Columbus, the Americas were a self-contained ecosystem sealed off from the rest of the world by two massive oceans. After Columbus came conquest and genocide but also new animals, plants, peoples, ideas, and diseases — in both directions. As this map shows, new things flowed into the New World from Europe, Africa, and Asia, and vice versa. This is the Columbian Exchange, and it made the world as we know it. Before the Columbian Exchange, there were no pineapples in Hawaii, no chocolate in Switzerland, and no coffee in Colombia.

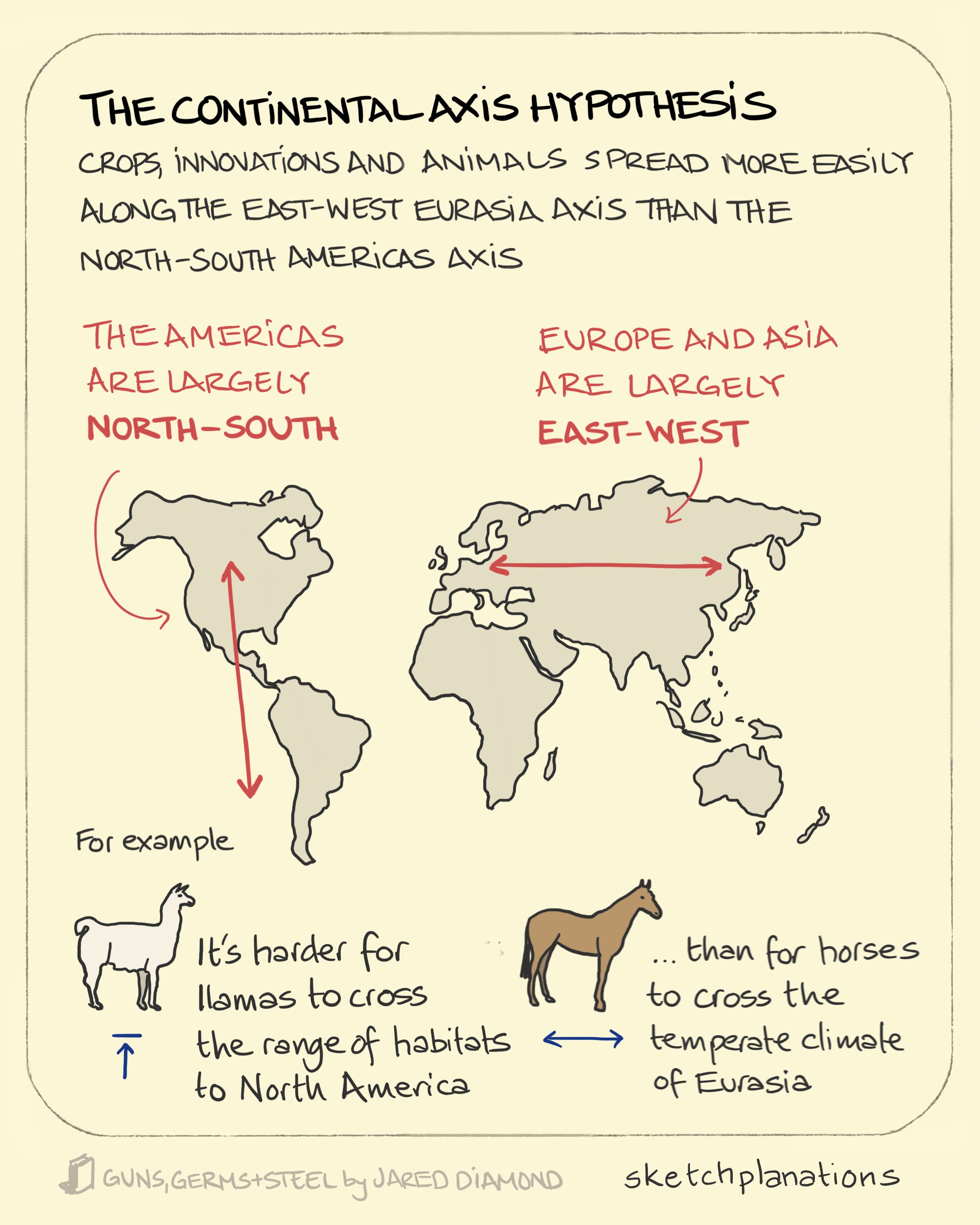

Of course, the Americas weren’t entirely isolated before Columbus; otherwise, he wouldn’t have encountered any people when he landed. The first human inhabitants of the Americas crossed over from Eurasia via the Bering Strait thousands of years ago. But that trip was extremely harsh and cold, so this “pre-Columbian exchange” was essentially limited to the people themselves.

It was Columbus himself who kick-started the Columbian Exchange. On his first voyage, he brought back to Europe six Caribbean Natives, plus some birds and plants. On his second voyage, he brought to the Americas wheat, radishes, melons, and chickpeas.

Defeat, subjugation, and near-extinction

Things soon escalated, and not to the advantage of Native Americans. On the face of it, they had more than a sporting chance against the Europeans. In 1491, the Incan empire was the largest in the world, and the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan was bigger than any city in Europe. Yet following first contact, Native empires and tribes faced not just defeat and subjugation, but also near-extinction. Around 1650, a century and a half after Columbus’ first voyage, the Native population of the Americas had declined by as much as 90%.

A major reason for that decline was the diseases the Europeans unwittingly carried with them. Native Americans had never been in contact with measles, malaria, diphtheria, influenza, and other illnesses that Europeans had grown somewhat immune to. They were decimated by the new diseases, with smallpox being the deadliest of the imports.

Just imagine if the reverse had been the case, and the Spanish conquistadors had dropped dead shortly after landing from some unknown American bacterium. Perhaps the flow of conquest would have been reversed, and the cities of Europe would now be crowned by Aztec pyramids instead of Christian cathedrals.

But that’s not how it happened. The only major disease that made the journey in the other direction was syphilis, and even that’s debatable (for more, see Strange Maps #1128). It’s also no coincidence that this is how it happened. Americans before 1492 were isolated from the rest of the world and its diseases. Europeans, on the other hand, live on the “world island” they share with Africa and Asia. There are no natural barriers to the migration of either people or diseases. Hence, there was massive death, for example due to plague, but also a greater immunity against various diseases. (Though, this immunity was far from absolute: It is estimated that smallpox killed around 400,000 Europeans per year in the 18th century.)

Animal farm

More benign, but equally transformative, was the introduction of various animal species that were previously unknown in the New World, such as pigs, sheep, goats, chickens, cattle, and horses.

Lacking natural predators, imported populations of horses, cattle, and sheep grew exponentially, and “de-domesticated” herds colonized and transformed large parts of the American interior. With plenty of grazing land to support huge populations of these species, there was always plenty of meat available. That’s a big reason why the Americas rarely experienced famine, and one more factor pulling in emigrants from the more precarious parts of the world.

Cattle, donkeys, and horses also gave Native American farmers and traders something they never had before: beasts of burden for pulling plows or carrying cargo. In contrast, the llama can carry just 100 pounds (50 kg). Various Native tribes enthusiastically adopted the horse, making it central to their culture. This allowed them to transition from an agricultural to a nomadic lifestyle.

Tobacco, chocolate, and potatoes

Turkeys and llamas traveled in the other direction, but these New World animals had a fraction of the impact a handful of American plants had on the Old World. First, tobacco. Smoking became so popular in Europe that tobacco farming helped sustain some of the earliest European colonies in the Americas, including Jamestown in Virginia. Another popular import was chocolate, although initially as a hot beverage.

Perhaps the Americas’ most consequential contribution to the global diet was the potato. The humble spud’s high-caloric value created food security for peasants, first in Europe and later elsewhere, that helped sustain a population boom. In just two centuries after 1600, the world’s population doubled, reaching its first billion around the year 1800.

There was a dark side to that success. When the potato crop failed, famine ensued. The potato blight in 1840s Ireland claimed a million lives through starvation. Another million Irish emigrated, mainly to America, setting a trend that would continue until a few decades ago. Uniquely among the world’s nations, Ireland’s population now (5 million) is smaller than it was in 1835 (8 million), right before the Great Famine.

Cassava, another American food export, provides more calories than any other food crop. It has become such a staple of African diets that many will be surprised to learn that it is originally American.

Both hero and villain

In the other direction went apples, pears, peaches, rye, barley, wheat, lettuce, citrus, and sugarcane. Sugarcane in particular thrived in the tropical parts of the Americas, and the need for cheap labor to work this and other cash crops created the most abhorrent element of the Columbian Exchange: the transatlantic slave trade. It resulted in the forced transport of up to 12 million Africans across the Atlantic, with about 15% dying from the abominable conditions on board.

Arguably, the Columbian Exchange was the world’s first experience of the phenomenon we now call “globalization.” Some of its effects were beneficial, many others destructive. In that sense, Columbus is the perfect figurehead for the phenomenon, as he is both hero and villain. But weighing up the good versus the bad is a pointless exercise. The world after the Columbian Exchange is an omelet that cannot be unscrambled. And besides, who would want to go back to a time before horses in America, strawberries in Europe, cassava in Africa, or pineapples in Hawaii?

Strange Maps #1212

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

Follow Strange Maps on Twitter and Facebook.