Syphilis: a disease so nasty that it was named after foreigners and enemies

- Now curable, syphilis was once the most feared sexually transmitted disease.

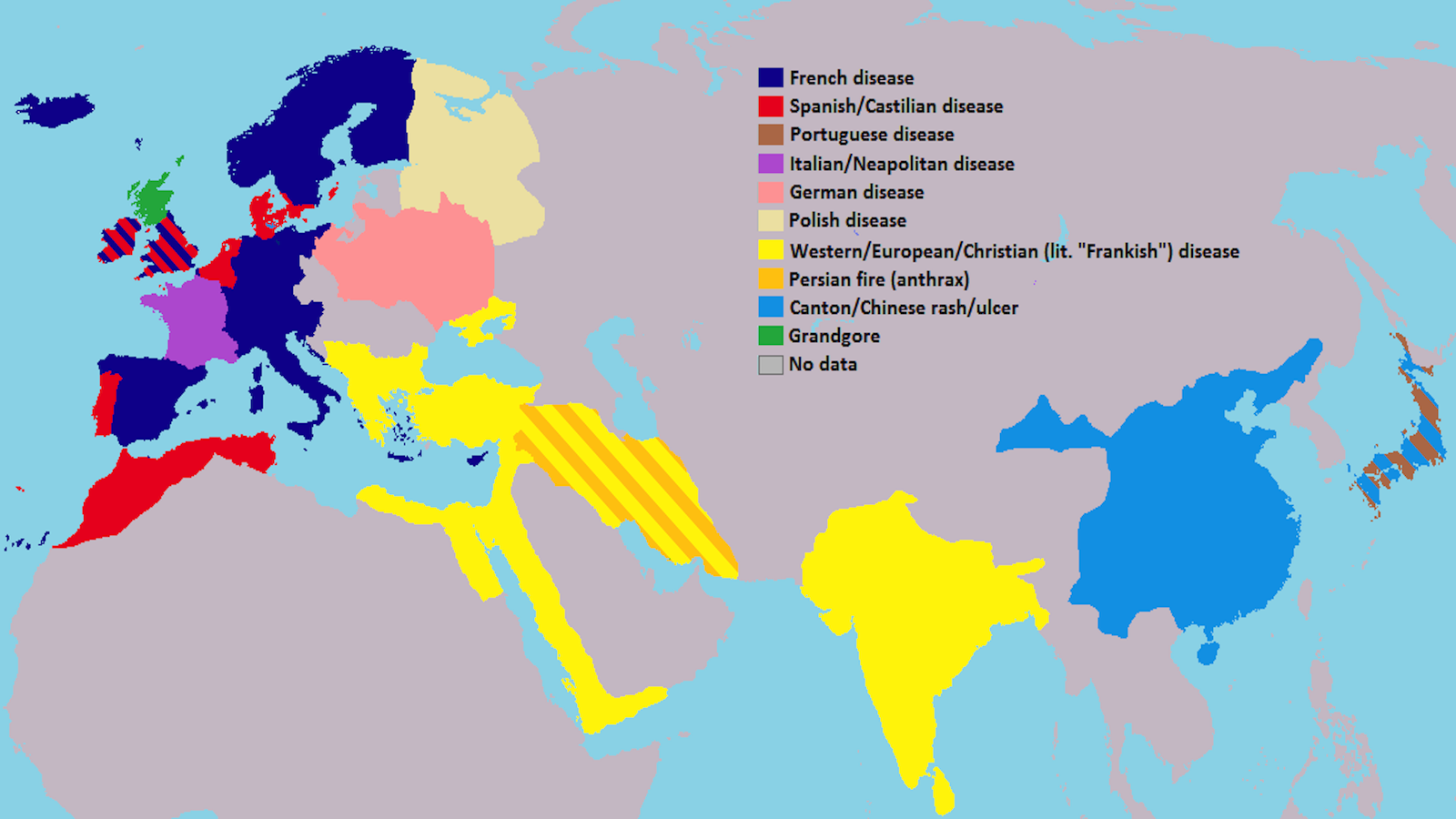

- As this map shows, it was so hated that, in many countries, it was known as explicitly “foreign.”

- The Italians called it the French disease and vice versa. To the Ottomans, it was the European disease.

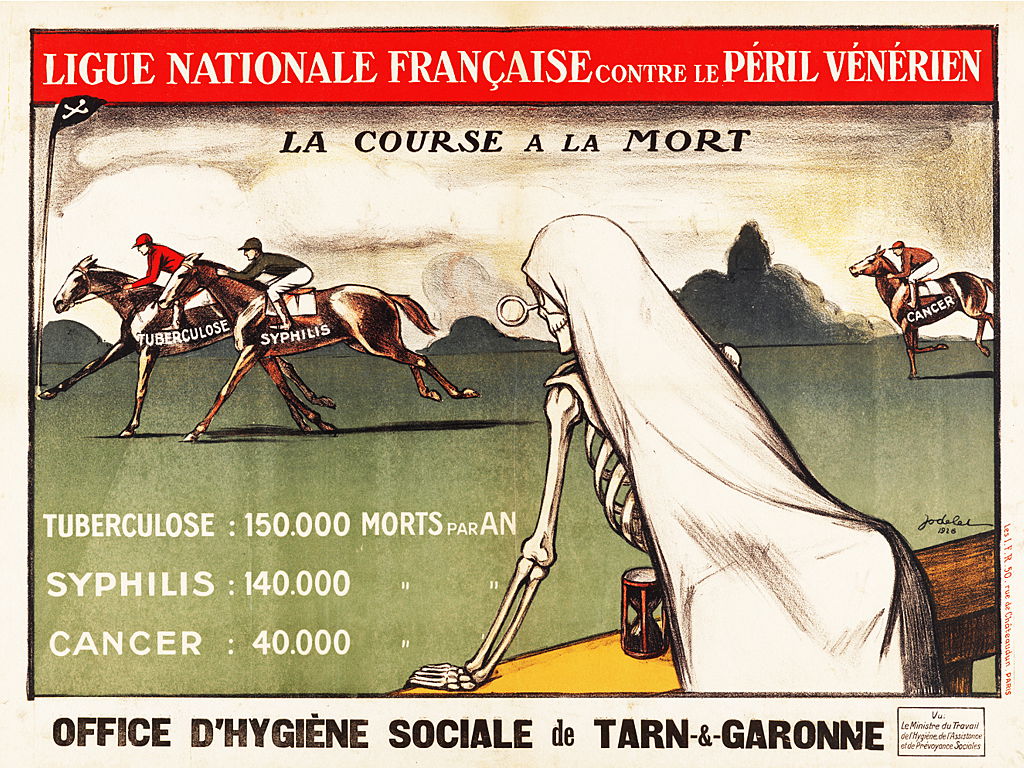

Imagine an AIDS epidemic that remains untreatable for a couple centuries instead of a couple decades, and you’ll get an inkling of the moral panic and physical suffering caused by syphilis — the most feared sexually transmitted disease (STD) of the last half-millennium, which could lead to gross deformities and insanity.

So repugnant, it must be foreign

This map shows one of the more curious consequences of the affliction: it was so repugnant that, in many countries, it was explicitly known as the “foreign” disease. The subjects of country X might be suffering, but really, the inhabitants of country Y were to blame.

That’s something our current pandemic has changed forever: we are no longer naming diseases after other places. When president, Donald Trump delighted in calling COVID the “Chinese virus” or even — mixing insult with accusation — “Kung Flu.” Those rather blatant attempts at deflecting attention away from the failure to contain the disease domestically may have helped to finally put an end to an age-old practice.

Because even a few years ago, few people batted an eye about names like “West Nile virus” or “Ebola” (named after a river in DR Congo). Now, however, attaching the stigma of infection to places of origin has finally become unfashionable. It’s not just unnecessary and unfair but also often incorrect. The “Spanish flu,” for instance, was first reported in Spain only because that country was neutral in World War I and its press uncensored at the time. (The Spanish flu probably originated in Kansas.)

Hence, our conscious decoupling of diseases and their (apparent) points of origin. This also explains all those Greek letters for the COVID variants: alpha rather than “Kent virus” (after the English county), beta for a strain initially found in South Africa, and gamma for one that emerged in Brazil. The previously dominant delta variant was originally observed in India, while the most recent one, omicron, was first spotted in Botswana.

Previous ages were less squeamish about pointing fingers and didn’t mind apportioning blame and origin with one and the same term. Syphilis is a prime example. As a sexually transmittable disease, it came with a fair dose of shame and a handy party to blame: the other person involved.

Blame it on the swine-loving shepherd

The disease’s modern name derives from an ancient poem “Syphilis sive morbus Gallicus,” in which its origin is mythically ascribed to the blasphemy of a shepherd called Syphilus (confusingly, sys-philos is Greek for “swine-loving”). However, the subtitle of the work from 1530 already hints at its oldest nickname: morbus Gallicus is Latin for “the French disease.”

That takes us back to the first recorded outbreak of the disease, in Naples in 1495, during an invasion by French King Charles VIII and his multinational mercenary army. Italian doctors called it il mal francese. The French, however, called it the Neapolitan disease. The tone was set.

As the disease spread throughout Italy, Europe, and beyond — helped in no small part by the French king’s pan-European mercenaries — it became known far and wide as the “French disease,” including in Germany, Scandinavia, Spain, Iceland, Crete, and Cyprus. Its various other names also had a particularly antagonistic flavor.

In England and Ireland, it was alternately named after two mortal enemies of the English crown: the French disease or the Spanish disease. The latter was also popular in a number of Spain’s neighbors/enemies, including Portugal, North Africa, and the Netherlands. The Danes too named it after Spain. In Germany’s neighbor/enemy Poland, the affliction was known as the German disease. In Poland’s neighbor/enemy Russia, it went by the Polish disease.

Further away from Europe, all those distinctions blurred into one. Both in the Ottoman Empire and on the Indian subcontinent, syphilis simply was the European disease (or the Christian disease, or the Frankish one — all near synonyms). According to the map, in a rare example of introspection, the Persians themselves called syphilis “Persian fire.”

Throughout China — but most probably not in Canton (modern spelling: Guangzhou) — it was known as the Cantonese disease. In Japan, the choice was between the Chinese or Portuguese disease.

In short, when it has to do with sex, it’s always somebody else who is the dirty, rotten scoundrel. A similar naming practice was attached to condoms when that word was considered too scandalous to be uttered aloud. In England, they were called “French letters,” while in France, the term was capote anglaise (“English overcoat”).

As this map shows, one exception proves the rule: the Scottish term for syphilis is grandgore, a word that does not refer to any other nation. The term simply derives from the French grand gorre, which means “great pox.”

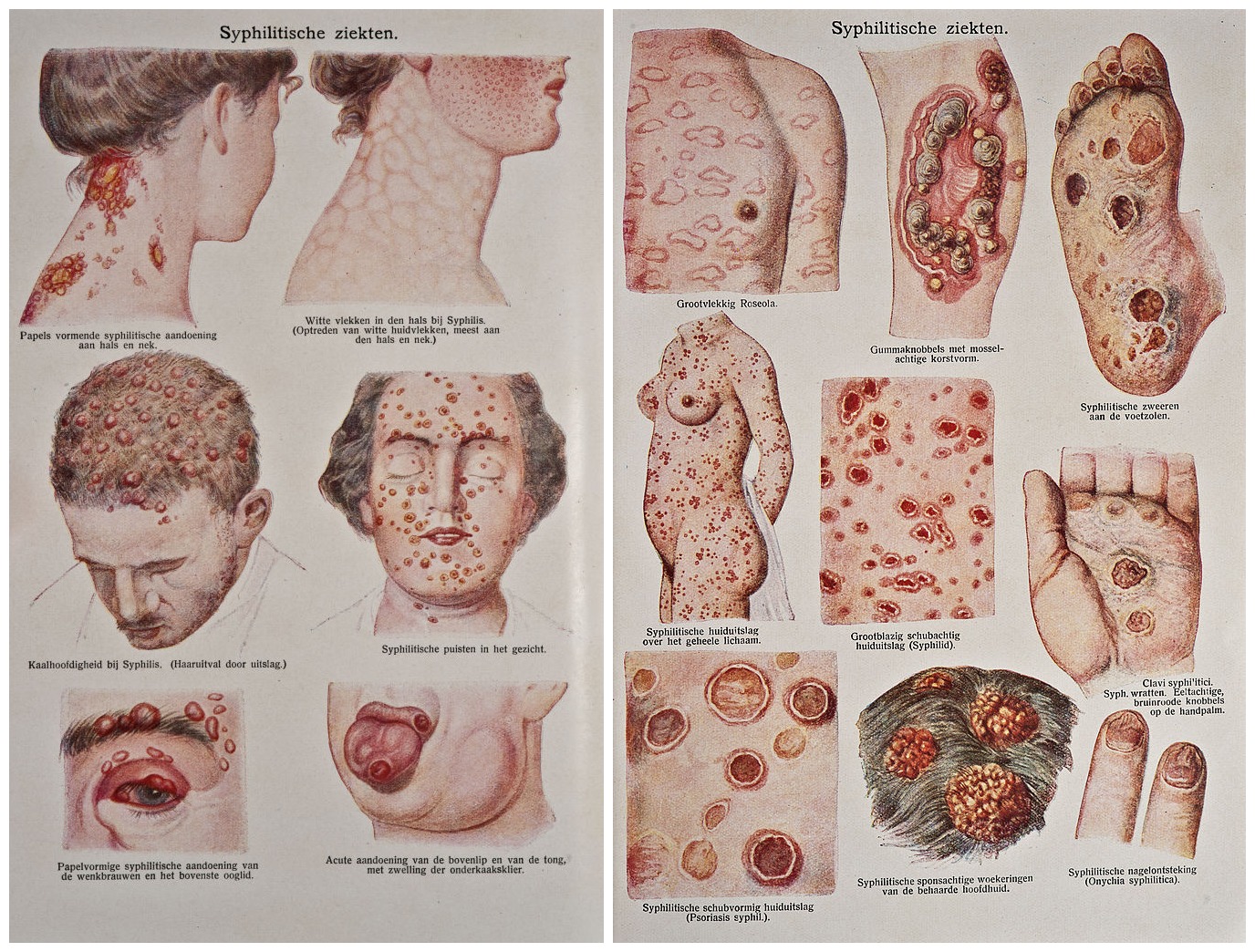

Syphilis starts as a painless sore (typically on the genitals, rectum, or mouth) and spreads via contact with these sores. Early symptoms include rashes, aches, fever, and hair loss. The disease may lay dormant for many years, resurfacing in up to 30% of cases. Syphilis may then lead to damage to the brain, heart, eyes, liver, bones, joints, and nerves.

Strangely, it is still not known how syphilis conquered the world. There are two hypotheses: a “Columbian” one, which says that it was imported around 1500 from the newly discovered Americas to Europe; and a “pre-Columbian” one, according to which the disease was also present in the Old World, but mainly mistaken for leprosy, until it became more virulent in the 15th century.

“Syphilis and the Cross of the Legion of Honor”

Many who held to the “Columbian” thesis used American plants like sassafras as a diuretic to treat the disease. Other treatments were based on administering mercury to the patients, often in toxic doses.

For centuries, syphilis ran rampant throughout the world. As it mainly affected the promiscuous, it became sort of a badge of honor in bohemian circles. As the French writer André Gide once said, “It is unthinkable for a Frenchman to arrive at middle age without having syphilis and the Cross of the Legion of Honor.”

The list of artists afflicted by the disease reads like a roll call of the famous and talented: writers like Keats, Baudelaire, Dostoyevsky, and Wilde; philosophers like Schopenhauer and Nietzsche; painters like Gauguin and Van Gogh; composers like Beethoven and Schubert; and even monarchs like Russian czar Ivan the Terrible and Maximilian I of the Holy Roman Empire.

Only in the early 20th century was the bacterium identified that causes the disease and were the first effective treatments developed. From the mid-1940s, penicillin became the main treatment.

Although curable in its early stages, syphilis still affects about 0.5% of the adult population worldwide, most of the cases occurring in the developing world. In 2015, it caused about 107,000 deaths, down from 202,000 in 1990. Since 2000, syphilis rates are going up again in the developed world, including in the U.S., Britain, and continental Europe. But at least nobody is blaming it on the French anymore.

Strange Maps #1128

Got a strange map? Let me know at [email protected].