Portugal is 97% Water

The average adult human consists of 55% water. A newborn baby is made up of about 75% water. A jellyfish contains between 95 and 98% water. Portugal could be a jellyfish: it is 97% water.

Which seems alarmingly aquatic for a country of 10 million, visited annually by at least as many tourists, all requiring solid ground beneath their feet at least some of the time.

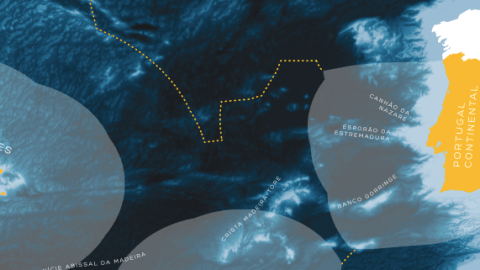

Why is this so? And how is it even possible? We’ll get to the why in a bit. The legend in the bottom left corner of this map says how:

This map of Portugal shows the land surface [in orange] and the territorial watersup to the limit of the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) [in light grey]. The proposed extension the continental shelf [dotted orange line] reveals [Portugal’s] new territorial dimension, which includes the seabed and subsoil beyond the 200 nautical mile limit.

This proposed, larger Portugal is the jellyfish version. Its 3% of dry land consists of three distinct territories: Portugal Continental, the Portuguese mainland, hemmed in by Spain on the Iberian Peninsula); and Portugal’s two autonomous regions: the Arquipélago da Madeira, a handful of islands closer to the (Spanish) Canary Islands than to Africa or Europe; and the Arquipélago dos Açores, so far out in the Atlantic that they’re almost halfway between Europe and America.

Each of these three territorial units is bordered (or surrounded) by ocean, the part of which closest to shore constitutes Portugal’s territorial waters.

In earlier, more artillery-focused times, territorial waters stretched as far as could be covered by a land-based cannon.This very practical method, at the basis of the long-held three-mile limit, became increasingly contested as cannon technology improved and was finally abandoned as an accepted mode of measuring sovereignty.

Only in 1982 did the UN’s Convention on the Law of the Sea put the disparate, disputable definitions of coastal territoriality on an even keel. Most countries now accept the premise on which Portugal’s territorial waters are also based:

A belt of coastal waters extending 12 nautical miles (22.2 km or 13.8 mi) from the low-water mark of the coast, unless it overlaps with another country’s 12-mile zone, in which case the border between both territorial waters is the median line between both low-water marks (unless both countries agree otherwise).

But this map doesn’t care for mere territorial waters. As can be judged from the scale on right of the map (on the Moroccan mainland), the grey zones are too extended to be only 12 nautical miles. They constitute Portugal’s Exclusive Economic Zone.

For the 1982 Convention also specified that a country could claim an EEZ of 200 nautical miles (370.4 km or 230.2 mi) beyond its coastal baseline. An EEZ allows a country to claim exclusive rights, but fewer than in its territorial waters.

In that first, 12-mile band, Portugal can claim total sovereignty (although it can’t preclude ‘innocent passage’ of foreign vessels). In the rest of the EEZ, Portugal also can’t prevent other nations’ ships from ‘loitering’. But it does retain exclusive rights to the EEZ’s fish and other natural resources in the subsoil (oil, gas, etc.) for itself to keep, or to license out to the highest bidder.

A few strategically placed islands can provide a gigantic (and potentially very lucrative) EEZ. Which partly explains why Argentina is so keen on Britain’s Falkland Islands, or why China and Japan are arguing about a few otherwise insignificant rocks in the East China Sea.

Portugal’s archipelagos provide it with three gigantic EEZs, almost contiguously stretching from 200 nautical miles west of Monchique Islet (the westernmost bit of Azorean dry land, geologically already on the North American Plate), all the way back to Lisbon.

The Azorean EEZ is the largest, at 953,667 km2 (278,045 sq nmi) followed by the Madeiran EEZ (446,108 km2 or 130,064 sq nmi) and the ‘continental’ one (327,667 km2 or 95,532 sq nmi). All this adds up to 1,727,408 km2 or 503,632 sq nmi), which gives Portugal the 4th-largest EEZ in the EU (after France, the UK and Denmark) and the 21st-largest worldwide.

That’s a lot of waves to rule for a small country, even one as historically seafaring as Portugal. But the 1982 Convention indicates there is even more to be had.

Under the conditions of the Convention, a country can claim part of the continental shelf (i.e. the shallow part of the ocean from which the dry land rises) adjacent to its territory. The Convention limits the claimable part to 350 nautical miles (648 km) beyond the coastal baseline, or 100 nautical miles (190 km) beyond the 2,500-metre isobath (a line connecting points at similar depth).

On the part of a continental shelf thus defined, a country can exert some rights, but fewer than in the EEZ proper: it has exclusive rights to harvest mineral and other ‘non-living’ materials from the subsoil, but it can’t prohibit other countries from fishing in the waters themselves.

On 11 May 2009, Portugal filed just such a claim, to an area totalling over 2.1 million km2 (more than 610,000 sq nmi). If the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf eventually validates Portugal’s claims, it will more than double the country’s zone of control, to 3,877,408 km2 (more than 1.1 million sq nmi).

Portugal is hardly alone in staking such a claim, a prudent move to prevent disputes over yet to be discovered resources. But few countries will be attaching visions of grandeur to dotted lines delineating as yet inoperable claims to resources under the seabed.

In Portugal, however, a glossy poster of the EEZs and the claim to the wider continental shelf, grandiosely titled Portugal é Mar (‘Portugal is the sea’) was distributed throughout the nation’s school system, to be tacked to classroom walls across the country. The map legend explains why:

The new map of Portugal shows one of the biggest countries in the world. With a maritime area 40 times greater than its terrestrial one, Portugal is 97% water.

See how big we are? Portugal’s claim to its continental shelf is not just economic, but also psychological: as an antidote to the country’s diminished stature on the world stage.

The Portuguese were pioneers of the Age of Discovery, and a world power to rival the Spanish for a good while after. Their empire stretched from Brazil to East Timor, and included colonies in Africa, India and China. That may all be in the past, but it seems Portugal is still suffering from post-imperial withdrawal syndrome.

They’re hardly alone in this – a wide variety of symptoms can be observed in countries like the UK and Russia, Turkey and France. But whereas the Brits (for example) hearken back to the world wars they’ve won (almost single-handedly) and want to row their island out into the Mid-Atlantic where it will be further from Europe and closer to the Commonwealth, Portugal’s post-imperial anxiety is clearly size-related.

Like an entire country with a Napoleon complex, Portugal seems determined to prove to the world that it is not a small country. And this blog has the maps to prove it.

The paper trail stretches back to the Mapa Cor de Rosa (#545), published in 1887 as an attempt to will into existence a transcontinental Portuguese colony in Africa, stretching from Angola on the west coast to Mozambique in the east.

Portugal’s African ambitions clashed with Britain’s plan to establish its own transcontinental string of colonies, from the Cape to Cairo. London strong-armed Lisbon into abandoning its plans, a trauma that contributed to the fall of the Portuguese monarchy a few decades later, and still resonates in the country’s national anthem.

It also grafted a mantra onto the Portuguese national psyche that is echoed by the title of this latest map: Portugal não é um país pequeno (‘Portugal is not a small country’).

That mantra was visualised cartographically by placing Portugal’s colonies on a map of Europe, showing how Mozambique would stretch from the south of Spain to Bavaria, and Angola would cover a diamond-shaped part of the continent cornered by Belgium, Gotland, southern Ukraine and Albania (#390). Or, inversely, how Portugal itself would fit into Angola at least 10 times over. (#545, at the bottom).

These maps were produced in the last years of Portugal’s dictatorship (and empire), both of which ended with the so-called Carnation Revolution in 1975. Since then, Portugal has reneged on its European isolationism, joining the EU in 1986, together with Spain.

“Not so small, are we?” says José Cristóvão, who sent in this map, found here on www.sapo.pt.

Strange Maps #652

Got a strange map? Let me know at[email protected].