587 – Maps as War by Other Means

War, as Clausewitz said, is the continuation of politics by other means [1]. But sometimes, war itself is being continued by other means – cartographic means. Maps are an excellent propaganda weapon against a (geo)political enemy. We trust cartography instinctively to ‘show us the right way’, and thus be truthful; but maps always reflect the mapmakers goals, whether they are merely technical (how do I fit three dimensions on a flat piece of paper?) or overtly political.

This blog prefers historical examples of cartographic propaganda [2], as they provide useful distance from the fierce urgency of now. Few people these days will be appalled to see a gruesome, bloody 18th-century war sanitised as a leisurely game of billiards [3]. Perhaps because, even if it had never happned, that war’s hundreds of thousands of casualties by now would have been long dead anyway. And perhaps that is the essence of ‘historical distance’ [4].

But show propaganda maps of current conflicts, and all hell might break loose – not over the maps per se, but over the political points they’re trying to score. As this blog is not about politics, but about maps, this is something it tries to avoid. At least it does now, ever since that shouting match broke out over a map of Greater Albania, with proud sons of the Balkans calling each other, and each other’s mothers, horrible names.

But sometimes, cartographic propaganda is just too compelling, no matter how current the conflict. A little voice in me says: Publish and be damned [5], however great the risk of a Comment War. For the juxtaposition of these two maps is just impossible to resist. In order to discuss them, some geopolitical context is necessary.

The theatre of these maps is the Holy Land, that dagger-shaped nation between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River. The conflict is about that land, and between two parties that reluctantly, untenably share it: Israel and Palestine.

Extremists on both sides want the same thing: the whole land united, the other side removed. The moderates disagree more subtly: Yes, the land must be divided between two peoples; but how? And where? And at what cost to national security, prosperity and dignity?

As moderation, in the form of the Oslo Peace Process, seems to have failed, extremists on either side seem bent on proving that they can win by being the title to a Bruce Springsteen song: Tougher Than the Rest. Not only do both extremes resemble each other, they also become increasingly ‘normal’, and moderation ‘abnormal’. From that festering disease of the body politic spring acute crises like the Gaza War, which has Gaza and Israel lobbing rockets and missiles [6] at each other.

Both sides are also lobbing maps at each other, both describing the entirety of the disputed territory [7], but each making a different – and in the present political context apparently mutually exclusive – point.

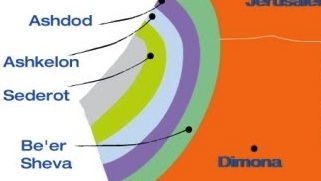

The first one is a map shading the territory of Israel/Palestine in concentric circles around Gaza, and in shaded zones in other parts of the country, relative to the reaction time the residents of those areas have to move to safe shelter after an enemy rocket is launched.

The circles around Gaza (the unnamed grey strip in the country’s far west) and the alarmingly red colouring in the north both broadcast the same message: these areas are under constant threat, and indeed frequent attack, by ever more sophisticated rockets launched by either Hamas (from Gaza) or Hezbollah (from southern Lebanon).

After the alarm is raised, Israelis in the green zone bordering Gaza have only 15 seconds to find refuge from the Gaza’s deadly export. Even in the furthest, olive green circle, the reaction time is no more than 60 seconds.

In the Golan Heights, and northern Galilea, red indicates that there really is no reaction time. Living in the yellow zone just south only allows for a 30 second sprint to safety. Together with the khaki zone, the red and yellow zones cover about a fourth of the entire country. Combined, the Golan, Galilea and Gaza hot zones give the impression of a country being gnawed at by a gangrenous infection; but even in the rest of the country, people aren’t safe for enemy rockets raining down. Tel Aviv, Jerusalem and even Dimona, isolated in the Negev Desert, are merely minutes away from a rocket attack.

The overall impression: Israel is a small, vulnerable country. It requires a strong defence. It needs to be especially vigilant, and if need be forceful, around Gaza and in the north, where its civilian population lives cheek by jowl with Hamas and Hezbollah, militantly hostile organisations that are both supported and armed by Iran.

The other map takes a historical perspective on the conflict, showing in four snapshots the reversal of the territorial imbalance between Jews/Israelis and Palestinians from 1947, just before the foundation of Israel, up until the present day.

Although Jewish immigration had been going on for a few decades already, immediately after the Second World War, Jewish settlements were concentrated in a small part of the entire Holy Land: the northern half of the coastal strip, and a U-shaped segment of Galilee. Squint your eyes, and the Jewish territories on that first map form the northern and western outline of what was to become the West Bank – that’s about as much is recognisable of the future state of Israel.

A UN Partition Plan in 1947 filled out the Jewish areas in the north, connecting Eastern Galilee, a coastal zone, and a large chunk of the south via two quadripoints [8]. Although this left much more of the Holy Land for the Palestinians than they could hope for now, it took from them much more than they had feared before. Israel’s unilateral declaration of independence, therefore, meant war. When the smoke had cleared, Israel had driven out Palestinians from even more areas than it had been assigned under the UN plan. From 1949 to 1967, the Gaza Strip and the West Bank (including East Jerusalem) were under Arab jurisdiction; their borders with Israel are the ones we’re familiar with as the internationally recognised borders of a future Palestinian state.

But in 1967, the Six Days War led to Israel’s conquest of Gaza, East Jerusalem and the West Bank. What followed, was occupation and colonisation. Only in densely populated Gaza was the Jewish settlement policy reversed; in East Jerusalem and the West Bank, it continues apace. The last map shows the result of occupation and colonisation: Palestinian-controlled territories are fragmented and reduced to a fraction – not only of Palestinian territory in 1947, but even of the West Bank in 1967.

The overall impression: a purposeful reduction of Palestinian-controlled territories in the Holy Land, inexorably moving towards their total elimination. Notice how the first map doesn’t show the outline of Gaza or the West Bank – the latter is subsumed in areas designated by Biblical names: Northern, Central and Southern Samaria.

No wonder that this attempt to push out Palestinians leads to a counter-push. Forget politics, simple physics predicts that an action will lead to a reaction.

Taken together, these two maps of the same land, but from such different perspectives, convey some of the paradox of the Israeli-Palestinian confrontation: a violent deadlock of two rights that make one big, fat wrong.

Fortunately, maps have the potential to be other things than propaganda tools. One day, hopefully, there’ll be a solution to the conflict that allows either side enough territory and dignity for them both to claim victory. That solution, too, will have a map…

Many thanks to Be’eri Moalem and Peter Dupont for providing me with the first and second maps, respectively.

_________

[1] Actually, not quite. In his seminal work On War (1832), Clausewitz wrote, in German: „Der Krieg ist eine bloße Fortsetzung der Politik mit anderen Mitteln“. That word can be interpreted as meaning ‘politics’ and ‘policy’. Which is not quite the same. That double meaning might have been Clausewitz’ point. Yet in the English translation, only the first sense of the word usually wins out.

[2] See #49, #103, #521, #561, among many others published on this blog.

[3] See #564, showing Germany as a theatre of war in the global conflict variously known as the French and Indian War, the Seven Years’ War and (in Germany itself) the Third Silesian War.

[4] It has also been defined, more broadly, as ‘the clarity of vision that comes with the passing of time’. That time-ripened perspective is the reason why Johan Huizinga, the famous Dutch historian of the Middle Ages, refused to lecture on ‘contemporary history’ (and perhaps also because it’s a contradiction in terms to begin with).

[5] As the angel on my other shoulder remains silent, I can’t really tell whether this is the voice of the one with the Better Judgment.

[6] All missiles are rockets, but not all rockets are missiles: a rocket is any self-propelled airborne projectile, while a missile is a rocket guided either by remote control, or via a carefully calibrated ballistic flightpath, usually understood to carry an explosive payload. So basically, a rocket is an unguided missile. The distinction is far from moot in the present conflict. According to the BBC at least, Gaza fires rockets into Israel, Israel fires missiles into Gaza.

[7] The territorial unity of the Holy Land – the Whole Land – is thus subconsciously promoted as a ‘Lost Eden’, and perhaps a future goal.

[8] For more on the genesis of the Israeli-Palestinian borders, see this episode of the Borderlines series over at the NY Times. See footnote [14] for more on the quadripoints.