See How Moscow Spreads Its Tentacles

“The plain is bleak and tired, and has surrendered,

The plain is bleak and dead – devoured by the city.” [1]

In Les villes tentaculaires, the symbolist poet Emile Verhaeren (1855-1916) indicts the insatiable hunger with which the modern city gobbles up the surrounding countryside.

Urbanity is not a modern phenomenon of course, but the spectacular, seemingly boundless growth of cities is. And as Earth’s population increase has accelerated over the last two centuries, an ever larger fraction of that population has become urban, a trend that has pushed the share of city-dwellers in the total population to over 50% for the first time ever in history [2].

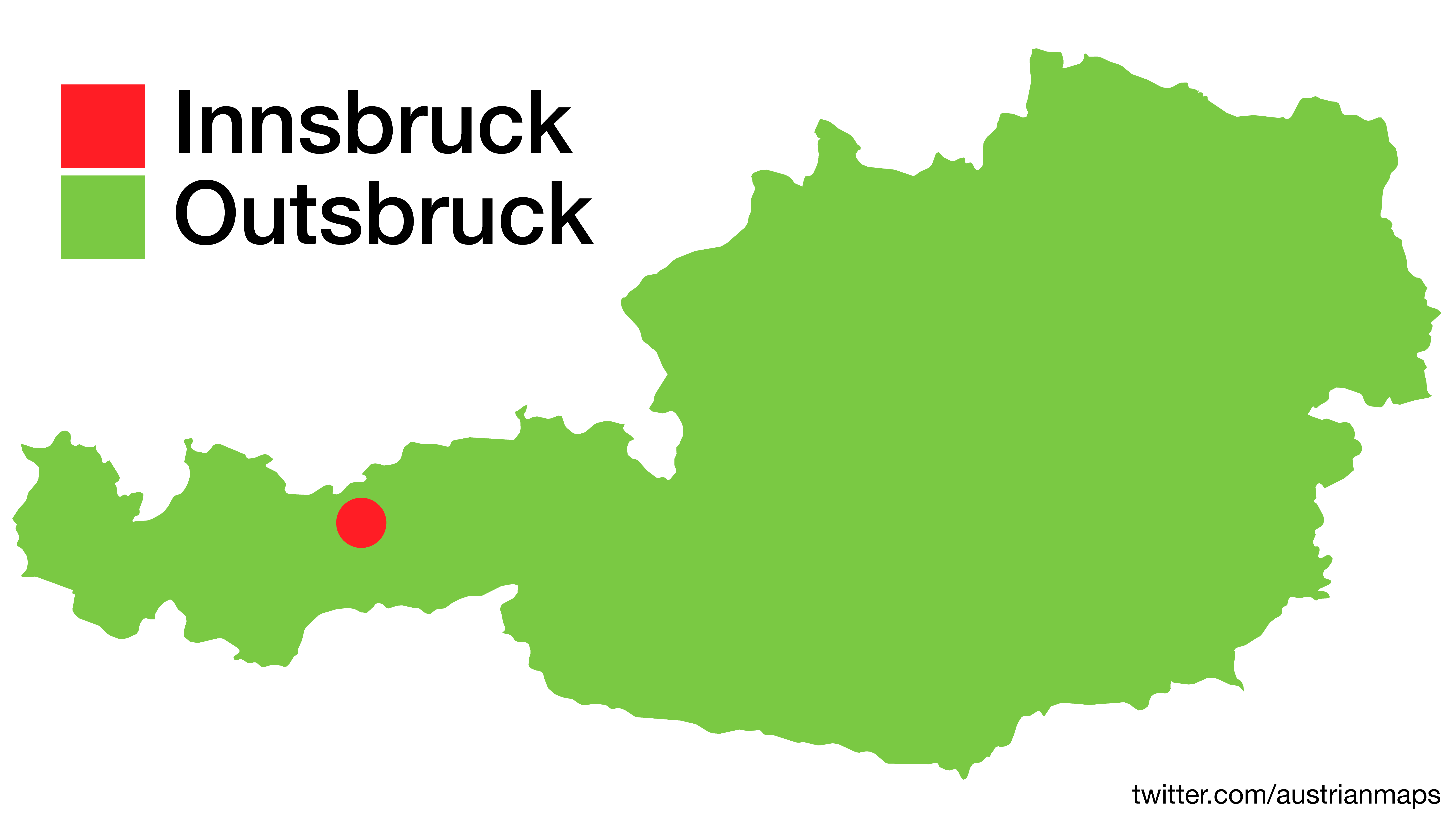

As they continue to grow, today’s cities are sprouting ever more tentacles, and on a grander scale, than Verhaeren foresaw even in his boldest poems. Few cartographic images bring to mind the tentacularity of modern urbanism more clearly than a map of Europe’s largest city, Moscow [3].

In 1900, there were already more than a million Muscovites. The second million was added by 1925, and by 1960, Russia’s capital counted well over 5 million inhabitants. In spite of this spectacular spurt of growth, the city’s infrastructural expansion continued on a pattern familiar in most pre-industrial agglomerations – and seemingly borrowed from nature [4]: tree ring-like growth.

Moscow’s mediaeval core is surrounded by a set of ever larger ring roads:

The 1980s is the time when Moscow seems to go into metastasis – aggressively devouring the ‘bleak and tired plains’ that surround the MKAD. Perhaps this tentacular expansion was enabled by a relaxation of communist-style central planning towards the end of the Soviet era. Or maybe even dyed-in-the-wool dirigists were daunted by the sheer monumentality of adding yet another concentric circle around the city.

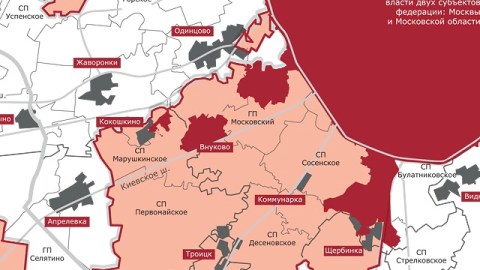

There doesn’t seem to be a pattern to Moscow’s trans-MKAD expansion. The blotches of annexed territory seem as random as the spatter produced by a child jumping in a Moscow-shaped puddle. On this map, there’s only one tentacle beyond the Moscow Ring Road’s eastern side; no less than six on the western side. But the annexations weren’t chosen at random: each seems to have a certain strategic, symbolic or practical value, warranting its digestion by Moscow, the nerve centre of the vast Russian state.

The first such territory was the district of Zelenograd (lit. ‘Green City’) in 1980, an exclave of Moscow to the northwest of its main territory. Zelenograd was a new town founded in 1958 as a centre for the textile industry, but later developed specifically as an electronics centre, a communist answer to California’s Silicon Valley. Until 1989, it was closed to foreigners. Now open to non-authorised personnel, Zelenograd remains a Special Economic Zone, and still houses the HQ of the National Research University of Electronic Technology, as well as other electronics R&D plants. There are plans for a high-speed rail link between this ‘Silicongrad’ and Moscow’s city centre.

That train would very likely travel through a salient, jutting forth from Moscow’s main body and almost reaching Zelenograd. This area is composed of two separate districts: Molzhaninovsky and Kurkino (marked ‘Aeroport’ on this map), both annexed in 1984. The main strategic importance of both indeed seems to be to connect Moscow to Sheremetyevo, Moscow’s answer to Heathrow [6]. The airport, located where the stylised aeroplane is shown, was transferred to Moscow proper in September 2011 – another tentacle probing deeper into its surroundings.

The extrusion expanding from near the MKAD’s northernmost point is called Severny (‘Northern [District]’), after the settlement of that name founded in 1950 to service the local plant of the Moscow Waterworks, providing drinking water to the capital. The area was annexed in 1985.

The easternmost extrusion consists of the Novokosino and the Kosino-Ukhtomsky districts, transferred to Moscow in 1986. These are the most densely populated areas of Moscow.

Towards the south are the Northern and Southern Butovo districts – the location of a firing range where from the 1930s to the 1950s tens of thousands of political prisoners were shot. In 1995, the range was sold to the Orthodox Church, which had canonised a number of those victims of the Great Terror.

Sointsevo (‘Sun Town’) was incorporated in Moscow in 1984. A bit further, a writer’s colony founded in the 1930s, Peredelkino (in the southwest) housed Boris Pasternak, Isaak Babel, Ilya Ehrenburg, Yevgeny Yevtushenko and (Turkish poet in exile) Nazim Hikmet.

Completing the circle, Mitinoin the northwest is an area of high-density habitation, annexed to the city.

Since this map, bits and bobs of other territory have been annexed to Moscow – among which Vnukovo in the south, another of Moscow’s three major airports – but no acquisition has been as radical as the one executed on July 1, 2012. The huge piece of real estate added to Moscow in the southwest on that day was a huge dam-breaker. The City of Moscow even broke through the surrounding Oblast [7] of Moscow, gaining a border with Kaluga Oblast.

“[It’s k]inda like NYC annexing nearby New Jersey territory until it borders Pennsylvania”, says Alex Meerovitch, who sent in this map. “The plan is to eventually turn Moscow into Russia’s Capital Federal District, sort of like the District of Columbia.”

First proposed by then-president Dmitry Medvedev in June 2011, the idea for the ‘New Moscow’ project was to enlarge the city by 2.4 times, dismantling the capital’s traditional monocentric structure. The enlarged Moscow jumped from 11th to 6th place in the ranking of the world’s largest cities (in area), but remained the 7th most populous one, as ‘New Moscow’ has only added about 250,000 inhabitants to its total.

The administrative map of Moscow found here.

Strange Map #567

Got a strange map? Let me know atstrangemaps@gmail.com.

____________

[1] “la plaine est morne et lasse et ne se défend plus,

la plaine est morne et morte-et la ville la mange.”

(taken from La Plaine, the opener of Verhaeren’s 20-poem cycle)

[2] That tipping point was reached in 2008. Back in 1950, only 30% of the world’s population lived in cities. By 2050, over 70% will be urban.

[3] Close to 15 million inhabitants, according to some sources. The size of urban populations is traditionally difficult to ascertain – it depends on where your definition of ‘urban’ ends. London, for example, counts anywhere between 8 million and 14 million inhabitants, depending on the definition used.

[4] As we’ve mentioned earlier on this blog, the growth of slime mould in laboratories can be made to mirror the expansion of traffic patterns across entire countries (see #xxx). Could it be that a similar organic simile underlies urban expansion?

[5] Short for Moskovskaya Koltsevaya Avtomobilnaya Doroga. Unofficially known as Doroga Smerty, the ‘Road of Death’.

[6] Conversion of a military airport to a large civilian hub was started after Khrushchev came home from the UK, impressed by London’s Heathrow airport.

[7] A Russian oblast corresponds with a ‘region’, ‘district’ or ‘area’ – as do the terms ‘okrug’ and ‘raion’. Obviously, this does not reflect their hierarchy. The city of Moscow is surrounded by the Oblast of Moscow. Moscow City is divided in 10 okrugs, each divided further into okrugs, totalling 125.