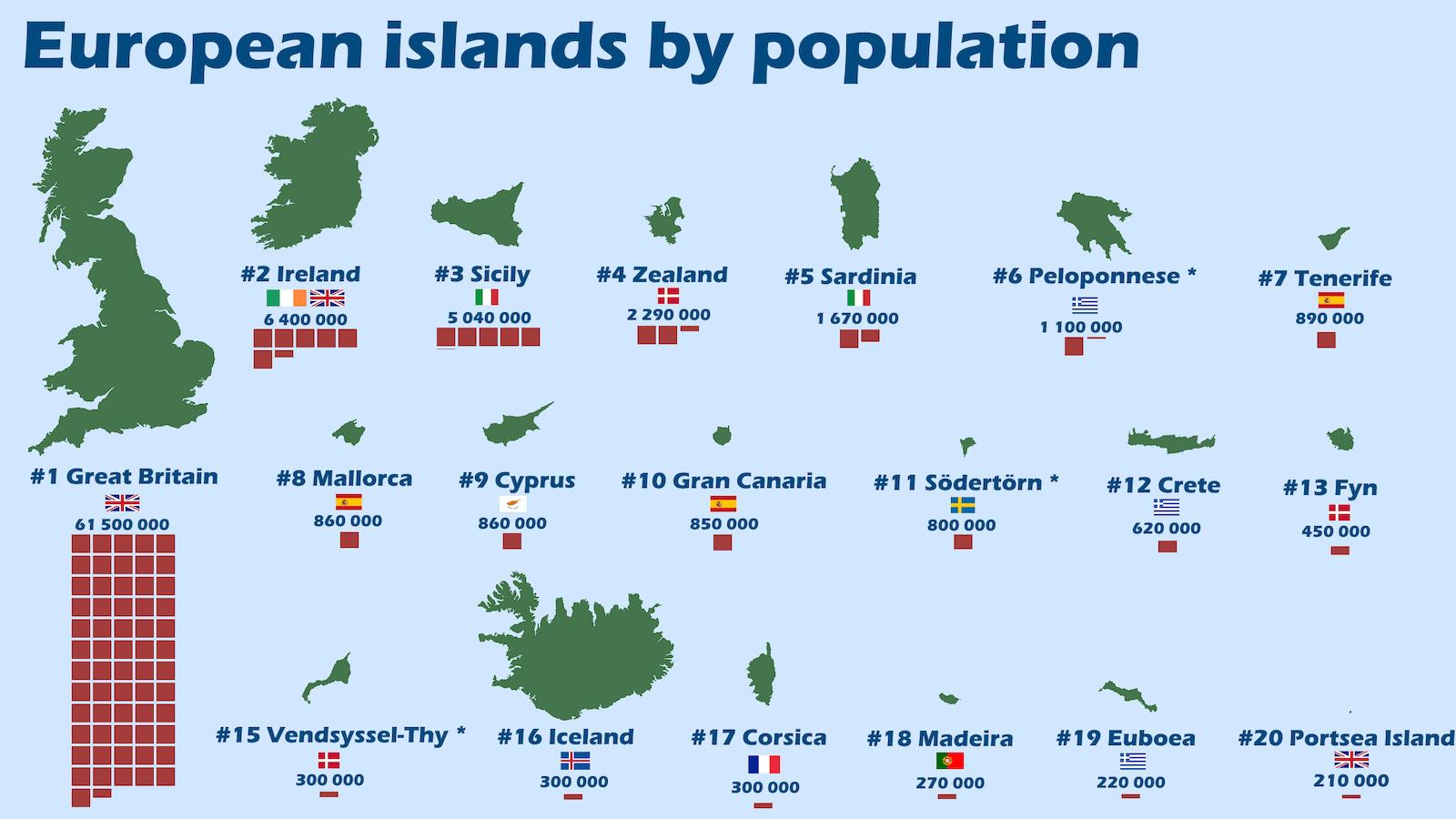

544 – Alphabet Maps of Great Britain and Ireland

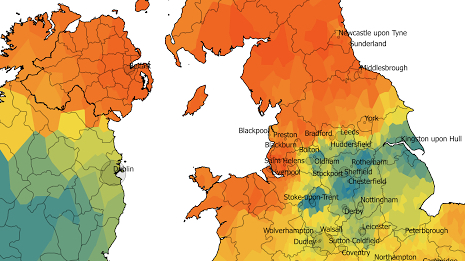

If you’re in the north of England and you’re in a town ending in -by, you’re in former Danish-ruled territory [1]. If the toponym starts with beau- or bel-, it was probably named by Normans [2]. And if it contains the prefix Avon- or the suffix -combe, it is one of many place names of Celtic origin that dot the islands on this map [3].

Analysis of place names can be highly informative of the languages historically spoken and ancient peoples once settled in any given country. The most obvious method for such an analysis is etymological. But what if we picked a more random pattern than word-origin?

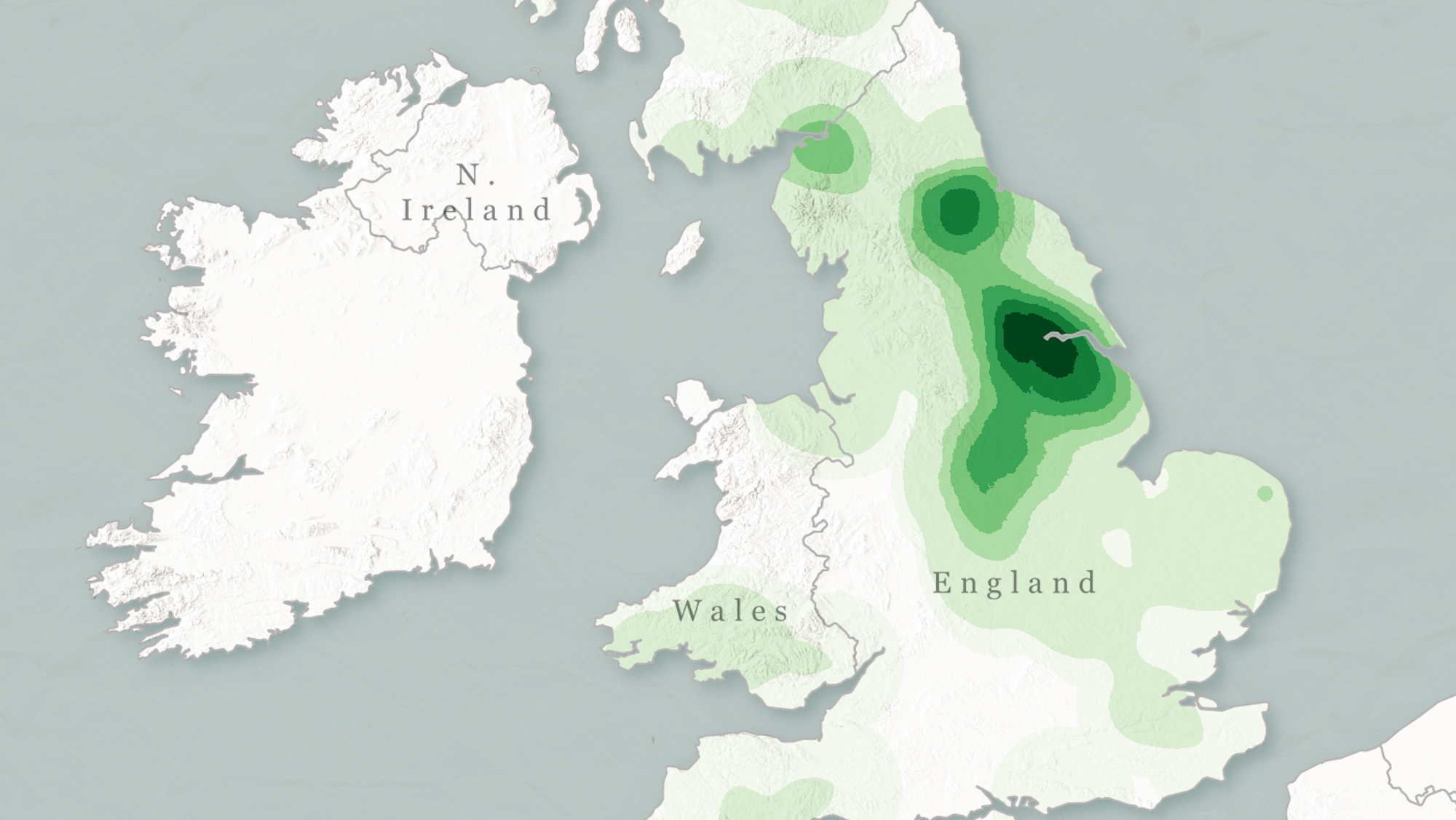

UK and Ireland (A through J)

What, for example, does a purely alphabetical analysis of place names tell us? It’s highly unlikely that settlers chose the names for their villages and towns by minding the Ps, Qs or the other two dozen letters of their alphabet. But that doesn’t mean that the patterns are completely random – just that there’s one more level of encryption between the pattern and its reader.

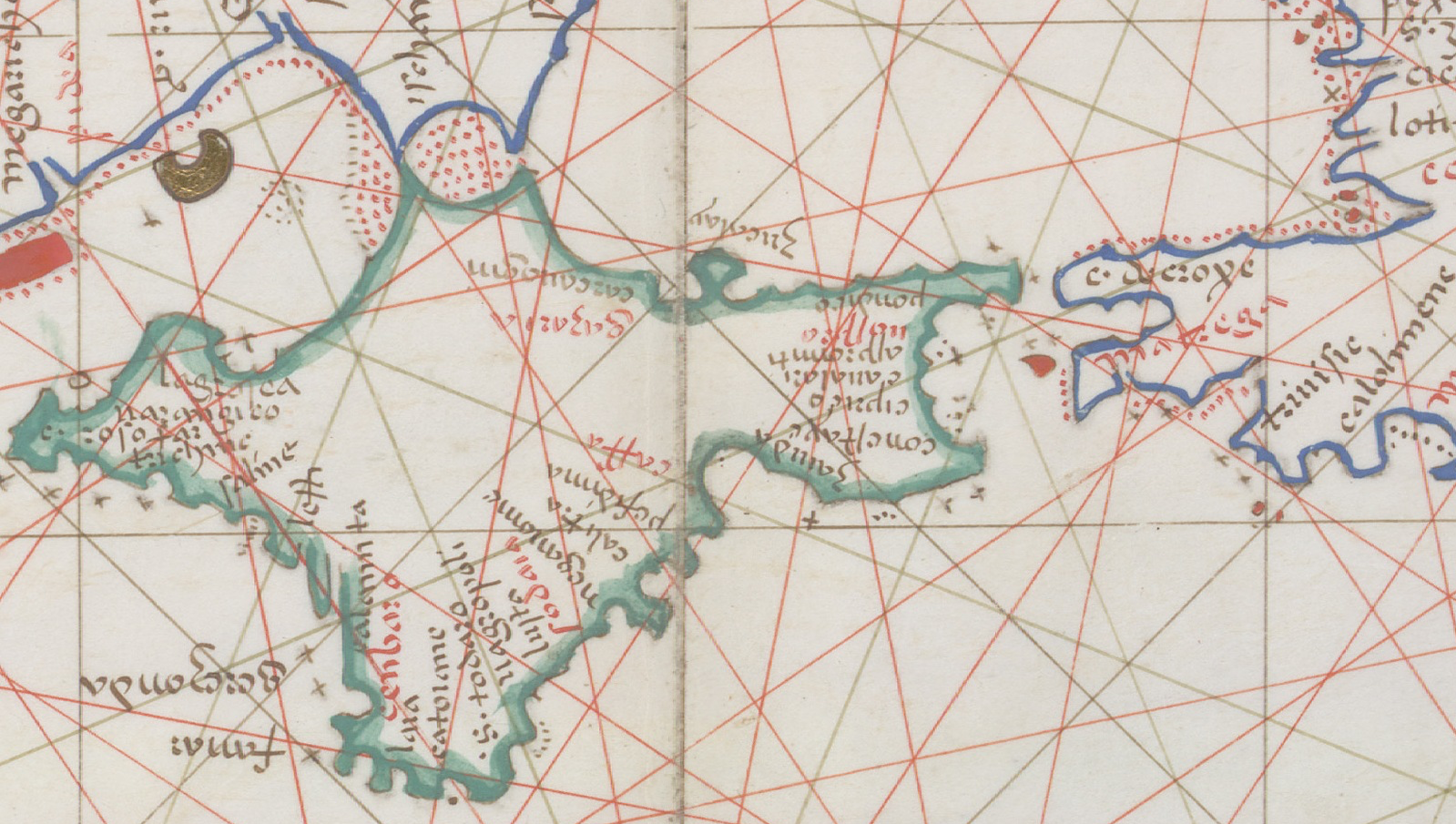

Take this series of 26 maps, each showing the density and distribution of British and Irish toponyms starting with each of the letters of the modern alphabet. Some observations:

UK and Ireland (K through T)

UK and Ireland (U through Z)

Many thanks to Mukund Unavane for sending in these maps, all 26 of his making (and located here), based on the data publicly available from the GEOnet Name Server (GNS) at the National Geopspatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA).

_____

[1] As in Grimsby, Wragby or Haxby. ‘By’(pronounced bee) is still the Danish word for ‘town’. Other originally Danish suffixes: -sted (Stansted), -thorpe (Scunthorpe), -toft (Lowestoft).

[2] Normans often renamed places they didn’t like the sound of, such as Fulepet (‘Filthy Hole’) in Essex, which became Beaumont (‘Fairhill’), or Merdegrave in Leicestershire, which was turned into Belgrave.

[3] e.g. Ilfracombe; the suffix still gives a good indication on how to pronounce its Welsh equivalent cwm, which also means ‘valley’.

[4] For earlier discussions on whether Ireland is or isn’t a ‘British’ island, see the posts and comments at #196, #514 and #535. My current opinion: like language in general, geographical nomenclature is subject to consensus, hence to change. So while ‘British Isles’ has the advantage of brevity (and some support in etymology), ‘British and Irish Isles’ is a perfectly acceptable alternative – if and when accepted by enough language users.

[5] See the poem Kubla Khan (1797) by Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

[6] Not on this map (at least not visibly), but mentioned by GEOnet.

[7] Perhaps most famously Llareggub, the (fictional) setting for Dylan Thomas’s Under Milk Wood. If you want to know where he got the name, reverse it.