United Data Communities of America

When you think of it, borders are paradoxical. They connect what they aim to divide. A borderline marks, with guillotine-like precision, where two territories separate; but no matter how far they expand in either direction, those territories resemble each other closest at their common boundary.

Borders can be impenetrable or irrelevant, and possess any degree of permeability in between: highly militarised, annoyingly bureaucratic, or merely symbolic. In any of those degrees, borders retain an iconic status. They’re humankind’s answer to the shorelines and mountain ranges of geology.

Without borders, a map is blind. With those lines, cartography is armed with a elementary tool for basic triage: here from there, us from them.

But those boundaries serve another function. They mould the territory they circumscribe into a reassuringly familiar shape. This geographic Gestalt is why, even though the genesis of borders is mostly obscured by history, and their relevance is often obsolete, we get worked up when confronted with an alternate set of borderlines.

Those alternate borders fascinate us because of their imaginative out-of-placeness. Take a look at Jefferson’s proposal for new states in the US’s new Northwestern Territories, for example: they seem all wrong – probably only because they never made it off the drawing board [1].

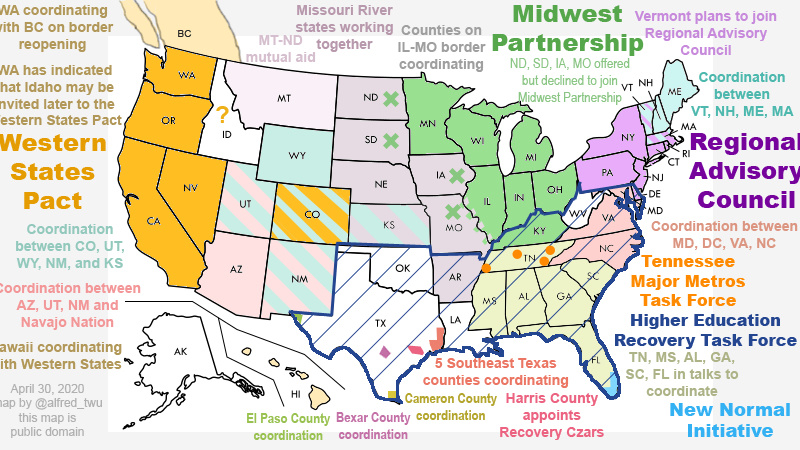

This map plays into our fascination with borders, both the iconic ones and their alternate versions. The linear base map shows the US subdivided into its constituent states and counties [2]. The colour overlay reveals so-called ‘call data communities’.

The extension of these areas was calculated by MIT and IBM, analysing anonymised call data. The map delineates zones in which people are more likely to call someone inside those areas rather than outside of them. The result is a revelatory re-mixing of states of America. Some split, others merge with their neighbours.

- Some states seem made for each other. People in Louisiana and Mississippi form an almost perfect telephone union. The only spoilsports are two parishes in northeastern Louisiana (grey, so probably inconclusive data) and five counties in northwestern Mississippi, more inclined to phone a Tennessean friend. Otherwise, the state lines correspond exactly with the Louisissippi call data community.

- An equally perfect fit: New England. Barring a few counties in northern Maine and New Hampshire, and an overspill of two counties in upstate New York, the inhabitants of Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Vermont, New Hampshire and Maine keep their calls pretty much a local Yankee affair.

- Other bilateral phone exchanges exist between both Carolinas – barring some Virginian infiltration on the northern shores of the Tar Heel State, and similar intrusions in North Carolina’s westernmost inland extension, and South Carolina’s southern border with Georgia.

- The latter two intrusions are part of an Alabama-Georgia phone zone, also extending north into southeastern Kentucky and into a significant chunk of the Florida Panhandle [3].

- Florida, in return, annexes two Georgia counties just north of Jacksonville.

- Another neat phone twin is Oklahomarkansaw. But Oklahoma loses its entire panhandle to No Overall Control, and Arkansas re-annexes the Missouri Bootheel [4] and nicks one county from Texas.

- Texas itself remains fairly homogenous, ceding only the extreme west of its territory across of the Pecos to a New Mexico-Arizona telephone alliance.

- Further west, a tri-state phone exchange exists between southern California, southern Nevada, and northwestern Arizona (plus a single Utah county). This Calnevari zone is bounded by a Northern California that is fairly modest in its telephonic expansionism (gobbling up only bits of Nevada), and a Utah spilling over into southern Idaho, and a slice of Wyoming (perhaps following Mormon settlement patterns).

- A phone zone relaying all of Washington State with most of Oregon and the northern panhandle of Idaho, plus another one fanning out from Colorado – without occupying all of it – complete the western call data communities.

- Halfway back east, a Greater Minnesota dominates Iowa and northwestern Wisconsin, even slipping into Illinois, Nebraska and South Dakota.

- Missouri is the central plank of a triptych, extending into Kansas and southern Illinois.

- The rumps of Illinois and Wisconsin have banded together, infiltrating Michigan in a two-pronged attack reminiscent of the Schlieffen plan [5], in the process also pocketing the bayshore of Indiana.

- Indiana, Ohio and Michigan are basically one-state call data communities, fighting off their neighbours’ attentions.

- Those include a mighty Kentucky-Tennessee alliance, bursting at the seams, and a peculiar conglomerate of West Virginia and western Pennsylvania.

- Most of Virginia is phoning almost all of Maryland; Delaware, southern New Jersey and eastern Pennsylvania are happy to talk to each other; and New York is yakking to the southern bit of its own state, the northern part of Jersey, and a teeny bit of Pennsylvania.

- What’s left is upstate New York, minus three counties, plus two Pennsylvania ones. And the rest is silence: you’ve run out of credit.

Some suggested names for a few of these new communication-based communities (or ‘communicities’). For upstate New York: Seneca. For the West Virginia-western Pennsylvania state: Monongahela, after the river (and the valley) that connects them. For Virginia and Maryland: Chesapeake. For more, see here at Underpaid Genius. Or here at the NY Times.

Many thanks for all who suggested this map: Jennifer Berg, Alex Meerovich, Serena Palumbo, Guy Plunkett III, and Jacob Schlegel. Hope I didn’t miss anyone. Original context here at MIT’s Senseable City Lab.

Strange Map #522

Got a strange map? Let me know at [email protected].

————————————————

[1] Another map of alternate US state borders, mentioned earlier on this blog: C. Etzel Pearcy’s 38-state proposal (#5).

[2] 50 states and 3,143 counties or county-equivalents, to be exact. The latter denomination includes the 64 parishes of Louisiana and the 18 boroughs of Alaska.

[3] For more on the history of the Panhandle’s separateness, see #84.

[4] The only part of Missouri extending below 36˚30’N, at one time called ‘Lapland’, because it is where “Missouri laps over into Arkansas”. It was included in Missouri rather than Arkansas on the lobbying of a local planter, who argued that the area had more in common with neighbouring Missouri river towns than with the Arkansas hinterland.

[5] The German opening move for the First World War. See #138.