Magical Siberia: A Russian Take on Middle-earth

A poor motherless kid and a runaway slave are floating down a mighty river, on the run from the authorities. Huckleberry Finn? Well, sort of. In a 1973 film adaptation of Mark Twain’s best-loved work, Huck and Jim speak Russian throughout, and river they’re navigating definitely doesn’t look like the Mississippi. It probably is the Volga, and the flat landscape that surrounds them exudes the melancholy bleakness that seems to chime with the Russian soul.

The movie is called Sovsem Propashchiy (Hopelessly Lost), and although a Soviet production from the middle of the Cold War [1], it has been called one of the more faithful movie adaptations of Twain’s American classic. Yet Soviet authorities were so nervous about their version’s perceived ‘anti-Americanism’ that they postponed its release by several weeks, to avoid embarrassing Comrade Brezhnev, then on a state visit to the US.

It wouid seem that fitting artistic content with another geographical context – and in this case, no doubt supplemented with a bit of ideological fine-tuning – leads to a strange kind of disorientation, providing fiction with an added layer of meaning that can have unintended relevance for the present. One has to wonder if something similar also happened with the translation into Russian of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit – the dwarves as toiling, dispossessed dwarves as symbols of the proletariat, the all-too-comfortable inhabitants of the Shire as petits bourgeois or, worse, revisionists?

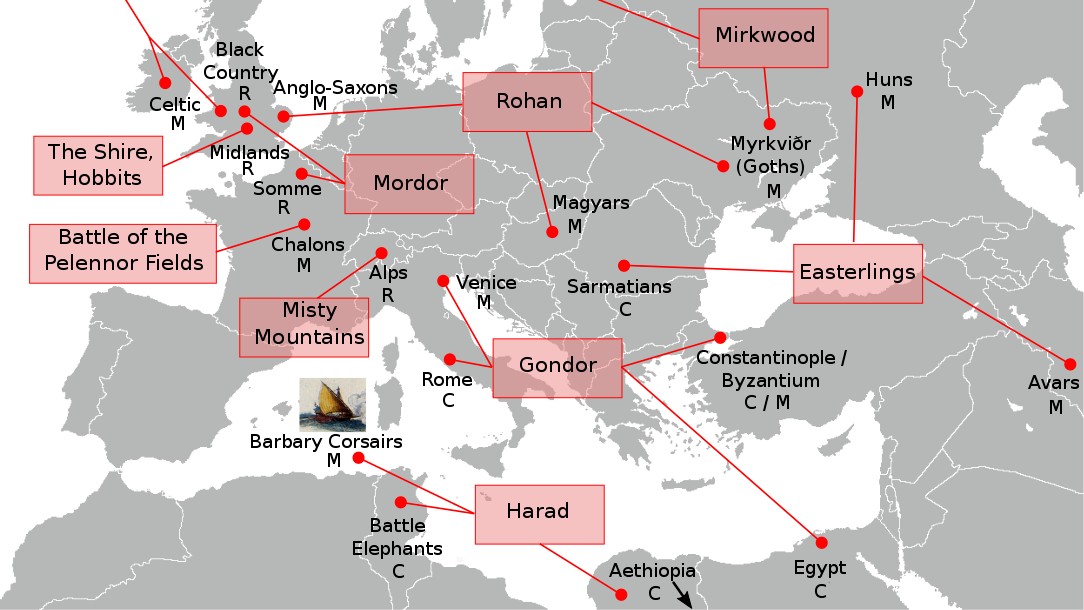

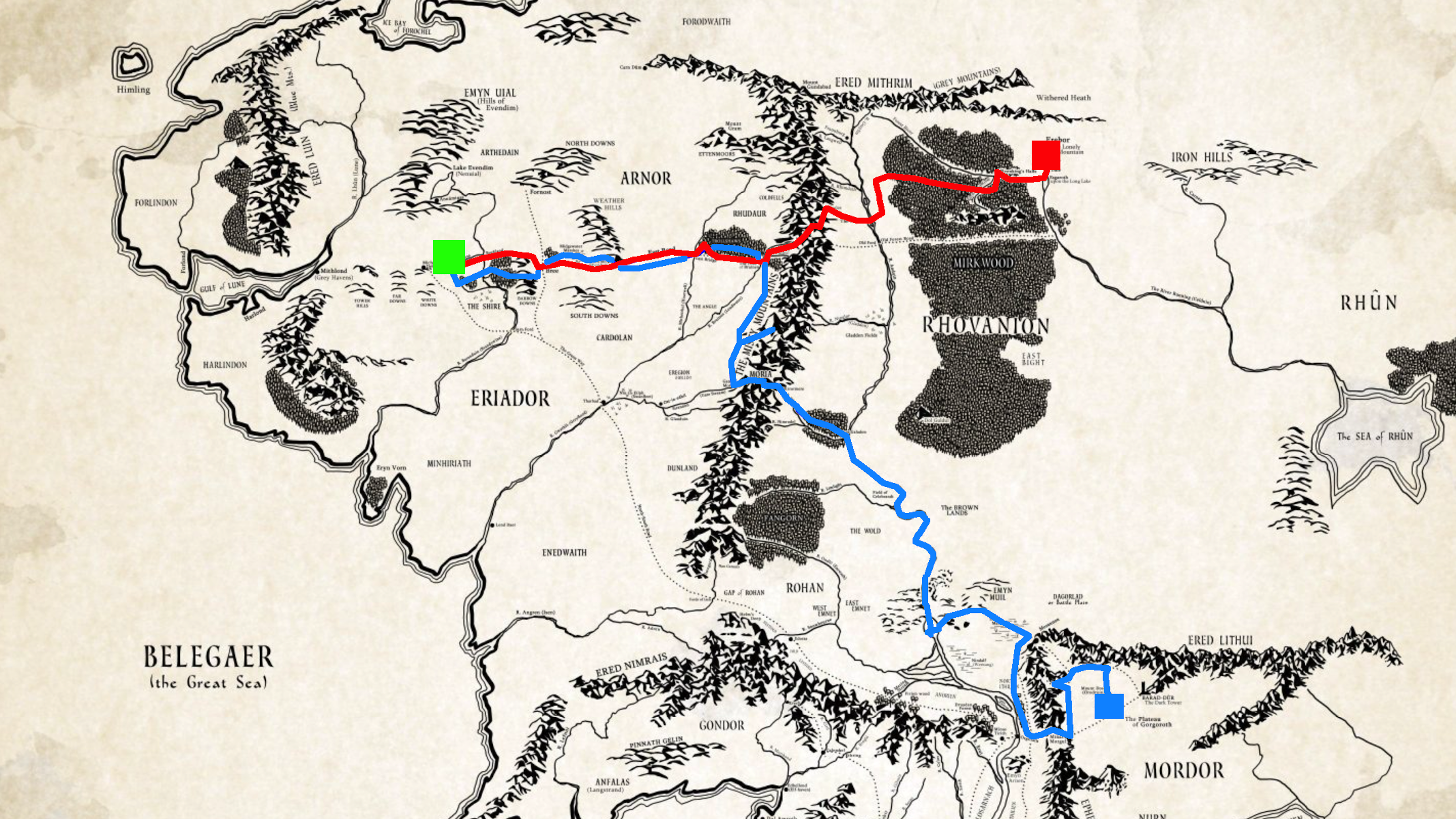

The Hobbit is the prologue to The Lord of the Rings trilogy. Both works describe Middle-earth, a mythical predecessor to our own time and place, give or take a few Ages. It is populated by Men, but also Elves and Dwarves, Orcs and Hobbits, Wizards and Ents, and many other creatures that seem to have stepped right out of (or rather: into) a fairy tale. Tolkien found the material for his yarns in ancient myths, and was inspired to spin them in order to provide England with the deep mythology he thought it lacked. The Shire and its inhabitants obviously are based on an idyllic view of the English countryside [2]. It is less clear on which parts of the present-day world, if any, the other regions of Middle-Earth are based. But some fun may be had in speculating [3].

This map, however, brings something definitely Russian to The Hobbit. The map is the work of Mikhail Belomlinsky, who illustrated a translation of The Hobbit, or There and Back Again by N. Rahmanova. The artwork provides the story with a decidedly Slavic ambiance, as incongruous here as it in the case of Huck Finn. Exactly what is so Slavic about this map – and whether or not it (or the translation itself) has socialist overtones – is a bit harder to establish.

- In the bottom left corner, we see what seems to be a collection of log cabins rendered in black, woodcut-like style: Хобитон (Hobbiton)

- One branch of an unnamed river, the first of three on the map, separates Hobbiton from Ривенделл (Rivendell); the other separates the latter from a place called последний домашний приют (posledniy domashniy priyut), the Last Homely House, as well as from дикий край (dikiy kray), literally the Wild Land, or the Wild Edge.

- What looks like a wolf and a mountain chain called туманные горы (tumanniye gori; Misty Mountains) separate the flatlands to the south from another river, containing скала каррок (skala karrok, or [the rock] Carrock) and beyond it a weathervane-topped wooden dacha, дом беорна (dom beorna): Beorn’s house.

- What looks like a large, dark, northerly pine forest is called, appropriately, чëрный лес (cherniy lyes), Black Forest. It contains a castle named дворец короля эльфов (dvoryets korolya elfov), the Castle of the Elf King [4].

- The river flowing out of the Black Forest is called, adjectivally, быстротечная (bistrotechnaya), the Swift [River]. It feeds долгое озеро (dolgoye ozero), the Long Lake, which contains the island city of эсгарот (Esgaroth), all black and with turrets, looking like little Middle-earth version of the Kremlin.

- In the top left, we see the железные холмы (zheleznye kholmy), the Iron Hills, and in the top right, одинокая гора (odinokaya gora), the Lonely Mountain, patrolled by a small-winged, heavy-breathing dragon. At the mountain’s foot we find the English name of Dale simply transliterated in Russian, instead of translated to the rather pleasing-sounding долина (dolina).

So what makes this a particularly Slavic map? The Cyrillic lettering helps, obviously. And so do the log houses (didn’t Hobbits live in holes?), the wolves, the pine trees and the dark, brooding, xylographically rendered landscape. All somehow adding up to the conceit as if Middle-earth were some kind of magical Siberia.

But maybe there’s a deeper link between The Hobbit and the Russian soul than even this map suggests. For it seems that this work by Tolkien, even if so much more lightheartedly narrated than the Ring trilogy, meticulously conforms to the 31 motifs [5] that form the structural basis for much of Russian folklore, as described by the Soviet scholar Vladimir Propp, in his Morphology of the Folk Tale (1928).

And what about those ideological shifts, mentioned above? We’d need a textual exegesis; little can be said from studying the map alone. But since this translation apparently dates from 1987 (or earlier still), Communist inferences might be present. Could this Russian translation reflect the secret indoctrination of Soviet youth into believing in a Comrade Baggins, from the Soviet Republic of the Shire, defeating the Big Bad Capitalist Dragon? Maybe, maybe not. Many things have been read into Tolkien’s work, but not yet, to my knowledge, a leninesque, pro-proletarian trait in the Hobbit psyche.

This map, found here, is part of a series, showing cartographic designs for foreign-language editions of The Hobbit, including maps in Portuguese, German, Swedish, Japanese, and Finnish (or Estonian, more probably).

Strange Maps #509

Got a strange map? Let me know at [email protected].

———–

[1] Hopelessly Lost (Совсем пропащий) was directed by Georgi Daneliya, who supposedly infused Twain’s epic with some of the trademark wit of his native Georgia (the mountainous Caucasus republic next to Armenia, not the Peach State just north of Florida). The film participated in the 1974 Cannes Film Festival, featuring Roman Madyanov as Huck, and Felix Imokuede as Jim. Madyanov would go on to be a mainstay of Soviet cinema, but Hopelessly Lost was Imokuede’s only acting job. The Russian-speaking African was a Nigerian student at Moscow’s Patrice Lumumba University, which catered to Third-World educational needs. Preferably those of Soviet-leaning countries. As Imokuede came from a ‘capitalist’ country, his actor’s biography was sexed up and he was ‘provided’ communist parents.

[2] “The Hobbits are just rustic English people, made small in size because it reflects the generally small reach of their imagination – not the small reach of their courage or latent power,” said Tolkien of the centrepiece race of his created world.

[3] See Strange Maps #121: Where On Earth Was Middle-earth?

[4] Black Forest in essence is a synonym of Tolkien’s name, Mirkwood, if a little less poetic. Similarly, the Castle of the Elf King is a literal translation of the Russian, but seems a a tad pedestrian when compared to the grandiloquent original: Elven King’s Halls. Do the translated terms sound equally terse in Russian, or is something lost in re-translation?

[5] These include absentation (leaving the security of home), unrecognised arrival (the hero arrives home or elsewhere, unrecognised), and transfiguration (the hero is given a new appearance).