Why Pluto Still Matters

Our love of the one-time ninth planet holds the key to our drive for venturing out into the Universe.

“I have announced this star as a comet, but since it is not accompanied by any nebulosity and, further, since its movement is so slow and rather uniform, it has occurred to me several times that it might be something better than a comet.” –Giuseppe Piazzi

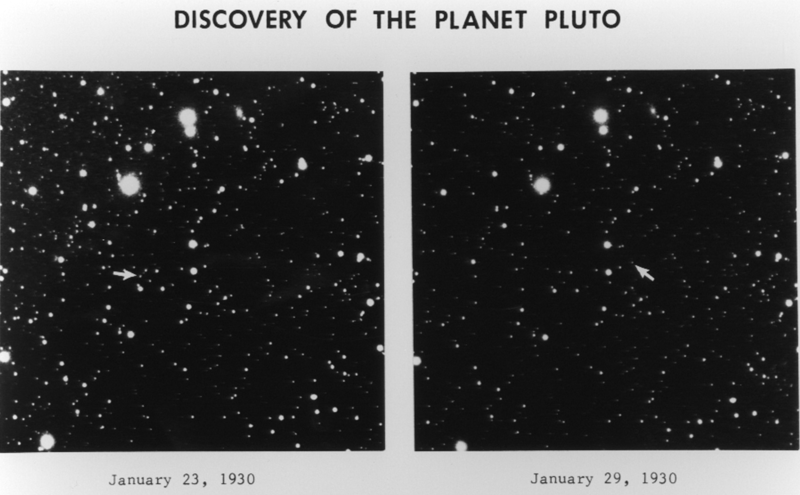

Next month will mark 85 years since a human being first imaged the motion of a world out there in our Solar System beyond the gas giants, the four massive worlds that compose about 97% of the Solar System’s mass outside of the Sun.

In January of 1930, a tiny, dim point of light was found drifting oh so slowly against the backdrop of fixed stars. Its faintness was a testament to not only how far away it was, but also to how small it must be, reflecting so little of the Sun’s light.

Yet at the same time, this object — serendipitously discovered nearly a century after Neptune — came as a shocking surprise to astronomers and physicists alike.

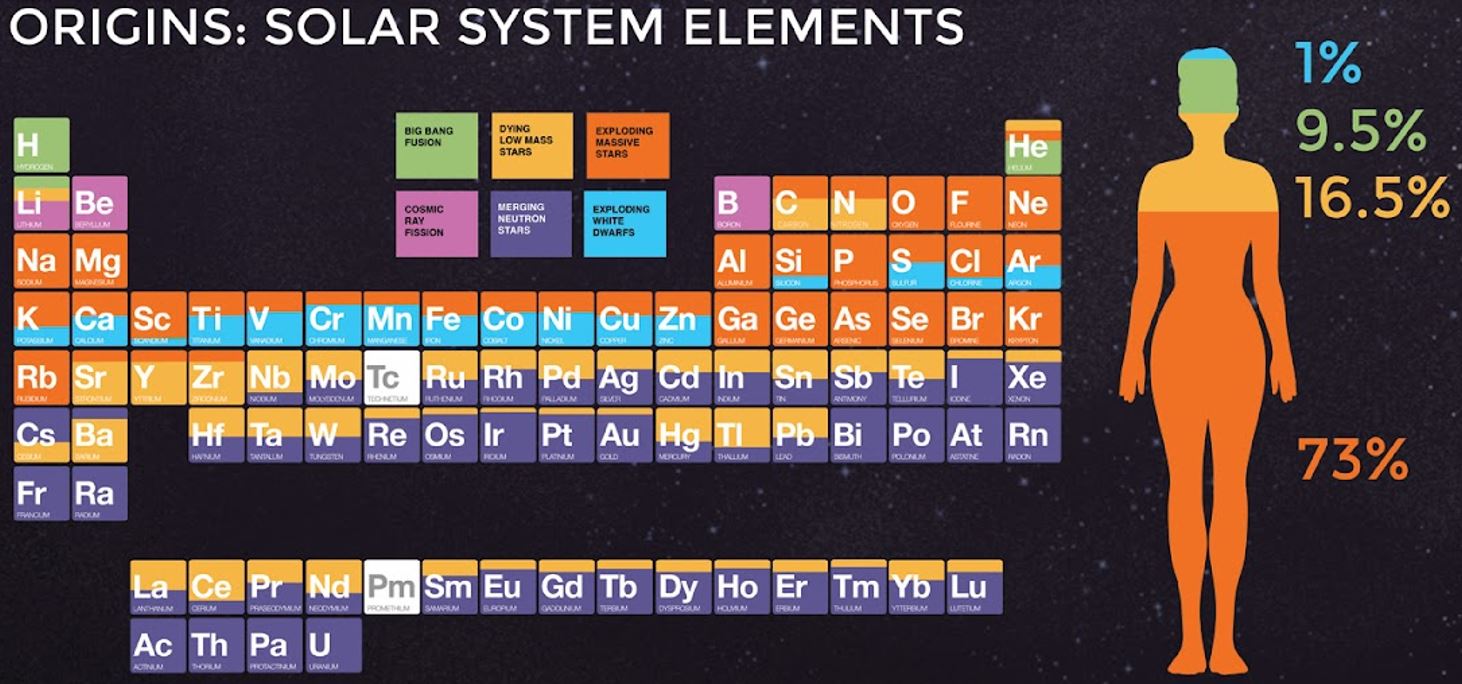

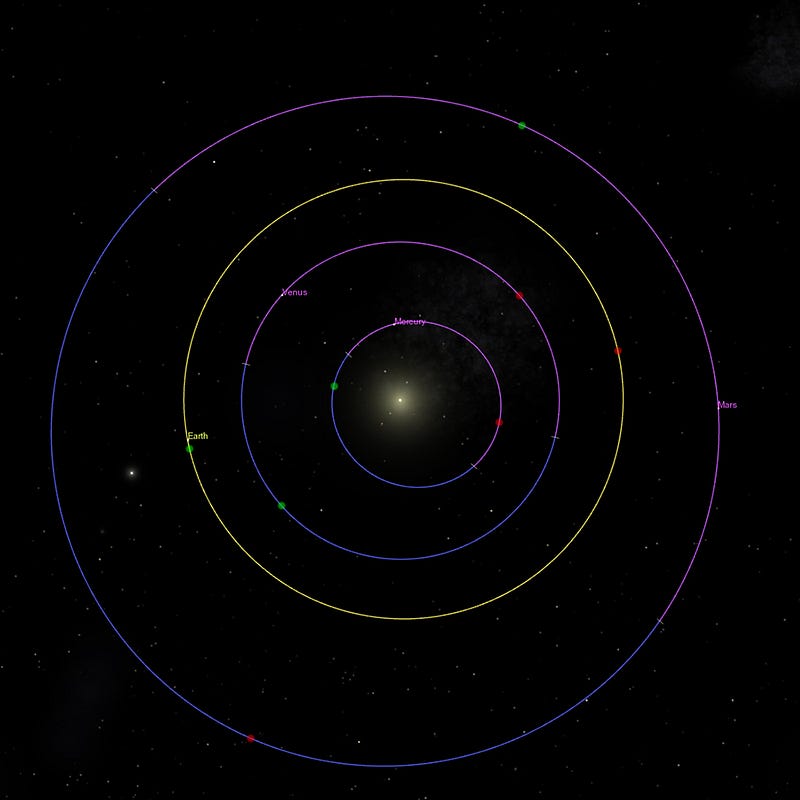

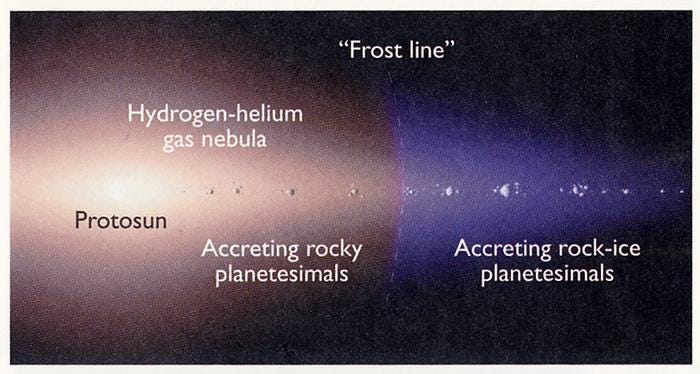

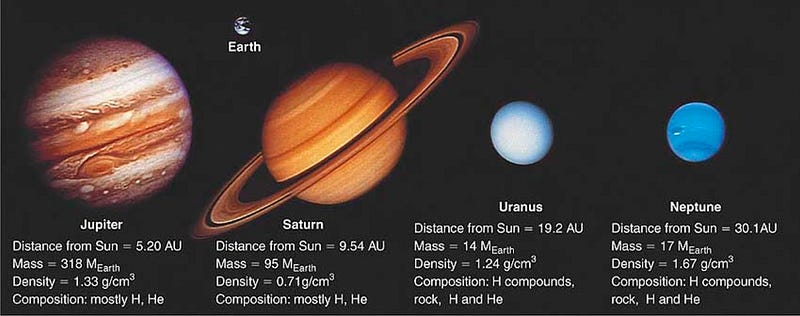

It made sense to have inner, rocky planets in a Solar System. The heat from the Sun ought to strip away the loosely-held lightest gases, hydrogen and helium, from planets. Although we now know that you can have gas giants in the inner Solar System, it made sense that rocky worlds would be the norm.

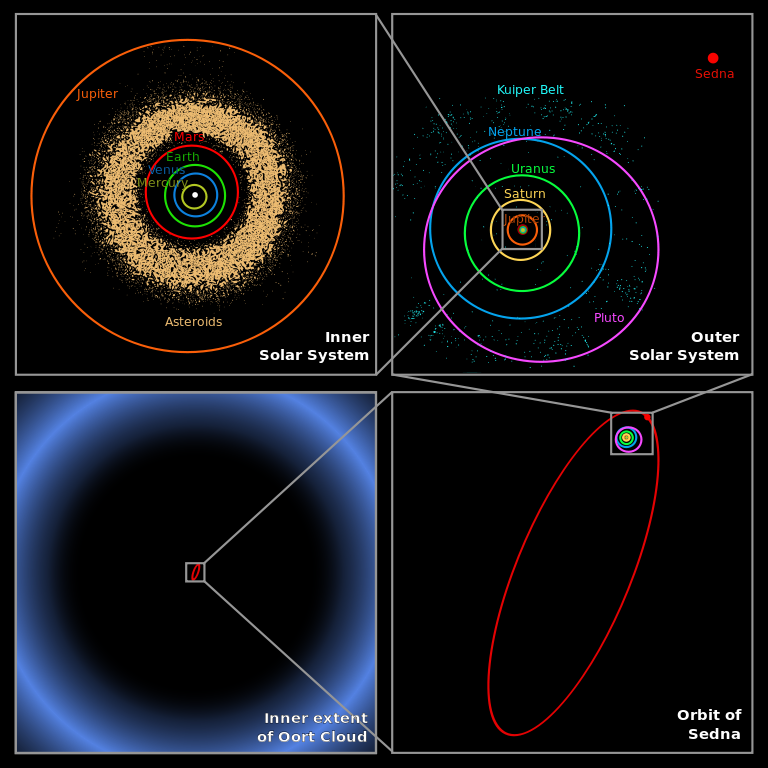

The asteroid belt was next, out beyond the orbit of Mars. Initially, the first object discovered in it, Ceres (discovered on January 1st, 1801, by the quoted Giuseppe Piazzi, atop), was thought to be yet another planet, but once its orbit and size were determined — and once many other asteroids began to be found — we recognized that Ceres wasn’t a unique object like Mars or Saturn, but rather was just one example of a large population of objects similar in composition and origin.

We now know that asteroids tend to form at what’s called the “frost line” of a Solar System: the boundary at which sunlight is warm enough to sublimate water-ice from a solid into a gaseous phase. Although we’re still learning about them, we suspect the vast majority of Solar Systems — basically all of them without a large planet very close to their systems’ frost line — have asteroid belts.

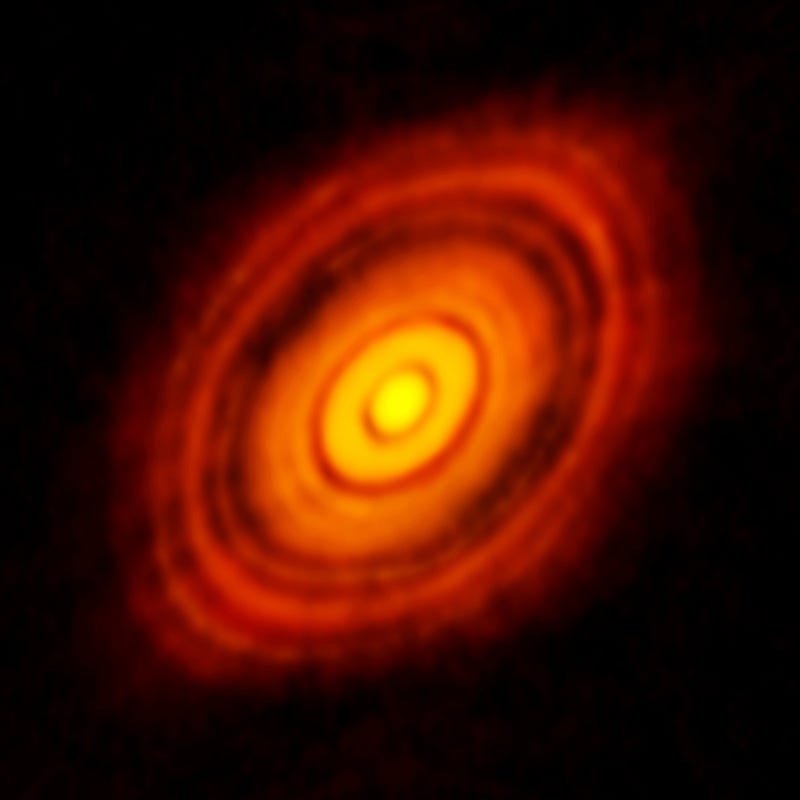

Beyond that are the gas giants. In many ways, it makes sense to view these as attempted, failed stars. Similar to the Sun, these grew from gravitational overdensities that most likely go back to the formation of the Solar System itself!

Attracting nearby gas, rock and other material from around it, these worlds grew rapidly into progressively larger and larger ones. As it is, Jupiter’s atmosphere is about 99% hydrogen and helium, and even its interior is about 95% composed of those two lightest elements. If Jupiter had grown to about 75 times its current mass, it would ignite nuclear fusion in its core, becoming a true star. Many star systems have two or more stars in them; it seems only a matter of chance that ours doesn’t.

Since ancient times, it was known that Saturn was more distant than all the other naked eye planets, and the discoveries of Uranus (in 1781) and Neptune (in 1846) pushed our Solar System out even farther. But even as telescopes and the science of astrophotography continued to advance, no new worlds were forthcoming.

And then, in 1930, all that changed. A world unlike any other was discovered: small and faint, more distant than all the others, with a highly eccentric, elliptical orbit: Pluto. Its orbit was far longer than all the other worlds: it takes 248 Earth years for Pluto to complete a single orbit. And although its designation and acceptance as a planet happened quickly — within months — it was realized over the subsequent decades that Pluto was smaller and less massive than most anyone has suspected.

Pluto remained alone at the edge of the Solar System for decades. Throughout the 1930s, 40s, 50s, 60s and most of the 70s, Pluto was all that was known beyond Neptune. It was simultaneously an object of wonder and a mystery, whose very existence begged the question, “what else is out there, beyond the last gas giant?”

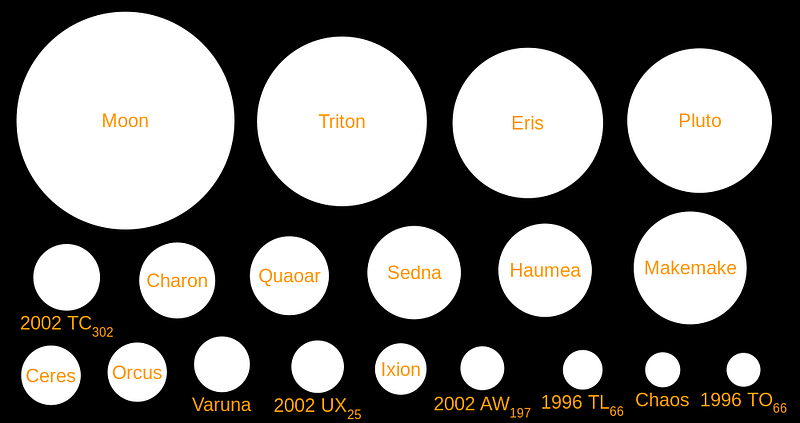

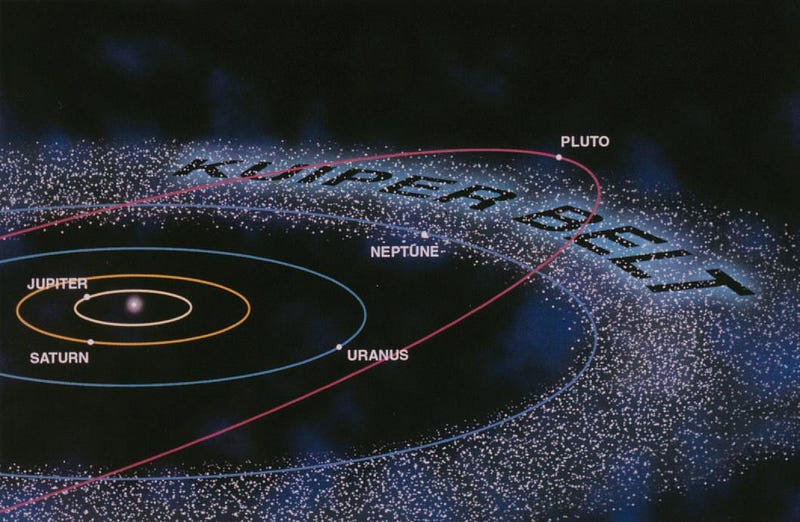

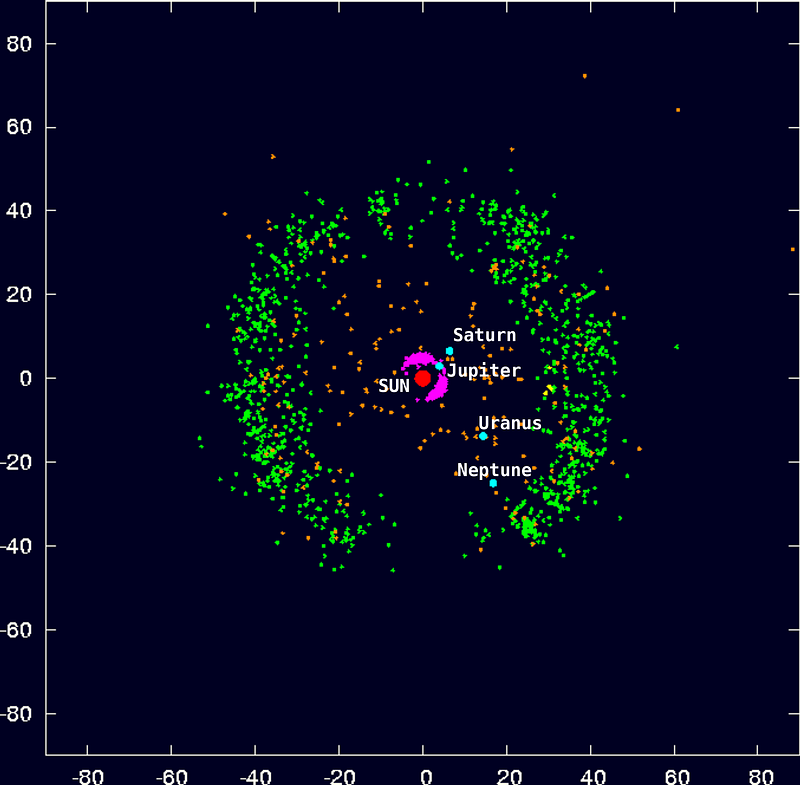

As it turned out, there was an entire suite of objects quite similar to Pluto: the Kuiper Belt. More than 1,000 Pluto-like objects are known to exist within it, and the total number of distant, miniature icy worlds may wind up exceeding 100,000 when all is said-and-done.

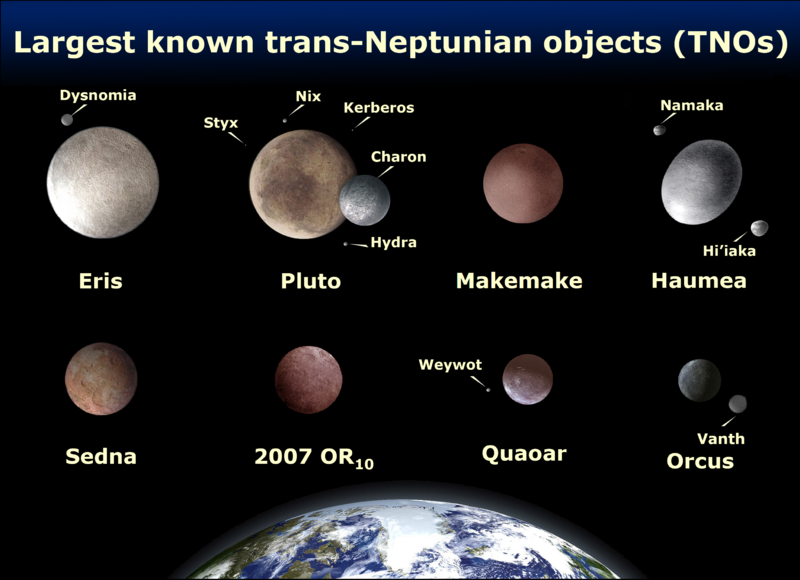

Although Pluto is still one of the largest and most massive, it no longer has the same mystique it once did. After all,

- it spent 48 years as the only known non-cometary object beyond Neptune,

- it was originally thought to be comparable in mass to Earth, yet is now known to be just 0.2% our planet’s mass,

- and it’s since been superseded in all aspects: mass, size, and distance from the Sun.

But it’s completely understandable why our sympathies for Pluto run so strong. It’s a small, almost insignificant body in all aspects. Compared to the titans of our Solar System, it’s barely noticeable. Its chilly, icy distance makes it incredibly hard to study, and yet perhaps that very aspect of it piques our interest.

But I think there’s something even more compelling at play here: most of us learn about Pluto as children, and as a child, Pluto reminded me of myself. It’s smaller than all the other planets, and it was the newest one to come along. To me, it represented all the undiscovered mysteries, all that was still unknown, and the hope that someday, it might matter more. I was actually rooting, as a kid, for Pluto to be bigger than Mercury, simply because I wanted it to be more important in some measurable way. And because it took longer to orbit the Sun than everything else, because it was different from all the other planets in practically every way, I truly believed it was special.

It’s been some thirty-odd years since I was that child, learning about Pluto for the first time, and in those same thirty-odd years, our estimation of the Solar System has grown to make it a larger, more well-known place. But in that same time, I’ve grown, too, and the most important lesson I’ve learned about Pluto — that I would have told my young self if I could — is this:

The fact that there are other things out there that are bigger, smarter, faster, stronger, or better than you, in any regard, in absolutely no way diminishes how special you are.

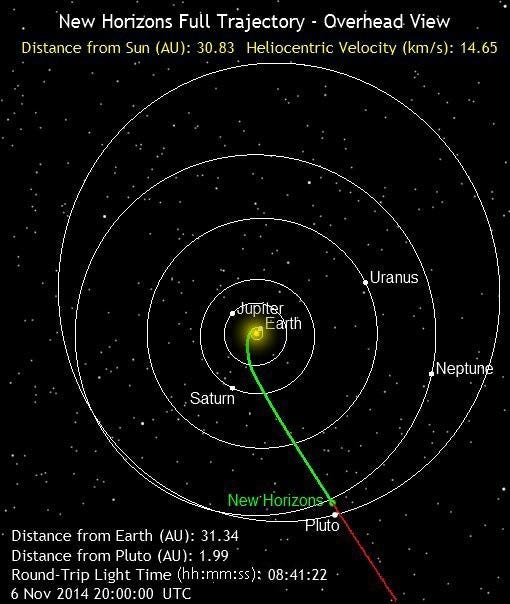

Next year, the New Horizons mission will finally reach the first Kuiper belt object ever discovered, and in doing so, will have the opportunity to study it up close for the first time.

We’re going to learn things about Pluto, its properties, its environment, its atmosphere and its surface that we most likely never imagined, and in doing so, will have our first in-depth understanding of what the most common type of planet-like object in the Universe is composed of, and of the Solar System beyond Neptune.

In our own way, we are all Pluto. It may not be a planet anymore, but it’s still special for exactly what it is, both in this Universe and to each one of us. A rose by any other name would smell just as sweet, and a planet by any other name would still be just as compelling, and would still call out to us, demanding to be known.

Leave your comments at the Starts With A Bang forum on Scienceblogs!