Why are the Perseids always so good?

The glorious meteor shower peaking this week is the most consistent, year after year. Here’s why.

“Men of genius are often dull and inert in society; as the blazing meteor, when it descends to earth, is only a stone.” –Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

There are plenty of meteor showers throughout the year, including many with names you’ve probably never heard of:

- The Quadrantids, peaking the first week in January,

- The Alpha and Theta Centaurids, peaking the second week in February,

- The Virginids, peaking in mid-April,

- The Lyrids, peaking just a few days after the Virginids,

- The Eta Aquariids, peaking in early May,

- The Arietids, peaking a week into June,

- The Perseids, the current (and famous) shower peaking mid-August,

- The Orionids, peaking about 2/3 of the way through October,

- The Leonids, peaking mid-November, and

- The Geminids, which peak in mid-December.

Of all these showers, the Perseids is the most consistently awesome to watch. Every year, without fail, you can expect a peak rate of about 100 meteors per hour so long as you have dark, clear, moonless skies.

Not only that, but the Perseids also put on a very good show, consistently, for days before-and-after the peak, where if you just go outside any night this week and look towards the northeast (for northern hemisphere skywatchers) after the Sun goes down for around ten minutes, you’ll probably see between one-and-five meteors at least.

And finally, the Perseid meteors are bright. They’re not all as bright (or large) as the one above is, but a few of them — visible each and every night that the Perseids are active — sure are. Many meteor showers have faint, non-descript meteors where you’re not even 100% sure you saw one, but when you see a Perseid, you’ll know it.

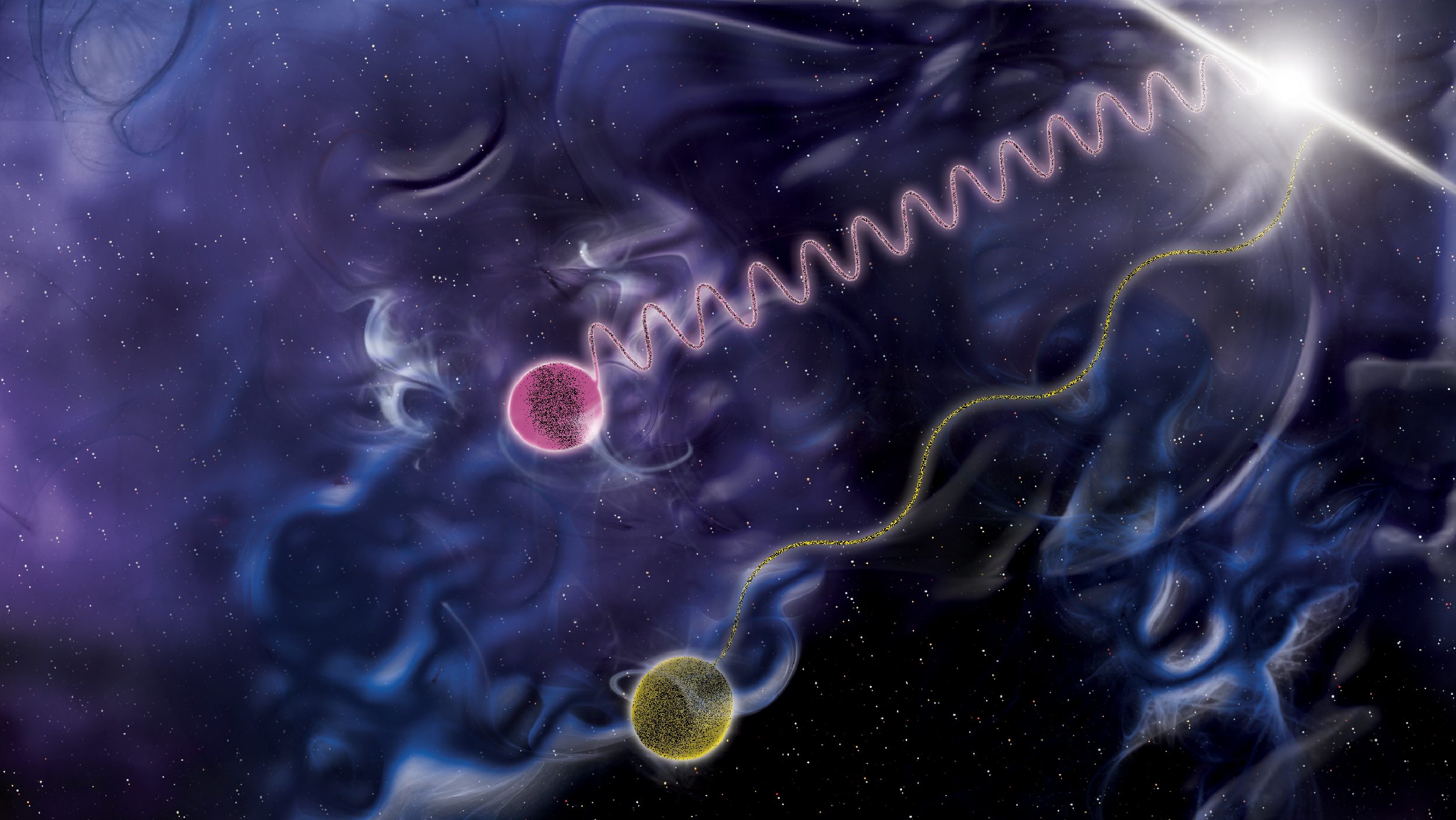

All meteor showers originate in the same way: a comet or asteroid hurtles through the Solar System, becoming active when it passes close by the Sun. This activity spectacularly produces two tails — a dust and an ion tail — but more importantly, the comet is heated throughout by the radiation from the Sun, and also experiences tidal forces from the Sun (and the planets it passes near) that help fragment portions of it.

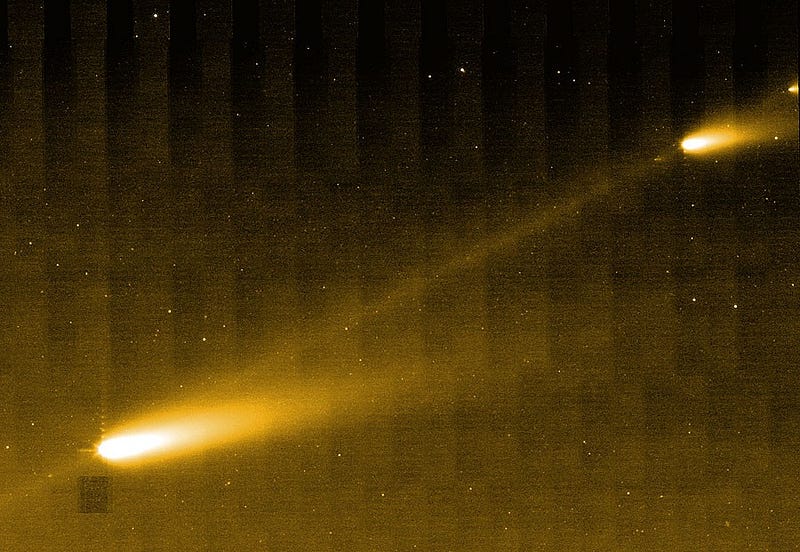

Fragmentation, for a long time, was just a theory, but then the Spitzer Space Telescope came along. Thanks to its infrared eyes, we were able to see this process in action, and verify that the nuclei of these objects are torn apart!

More importantly, do you see the “debris stream” in between the cometary fragments, above? Over time, these particles get stretched out into a giant ellipse, following the comet’s orbit. Whenever Earth passes through this imaginary ellipse, these tiny, grain-of-sand-sized particles collide with our atmosphere, producing the spectacular phenomenon of meteors. In the blink of an eye, the incredible speeds of these particles leads to a tremendous release of energy.

If you ever took introductory physics, you might remember that there’s a formula for kinetic energy: KE = 1/2 M v^2, where M is the mass of the particle in motion and v is the particle’s velocity. The mass of these dust grains might be tiny, but the velocity is tremendous! All meteors move at tens of thousands of miles per hour, but the Perseid meteors move an average of 133,000 miles per hour, giving them significantly more kinetic energy than many of the other showers.

In addition the comet that gives rise to the Perseids is Comet Swift-Tuttle, which is one of the most spectacular objects in the Solar System, at least from our perspective.

The object that struck Earth 65 million years ago, wiping out the dinosaurs and ending the Cretaceous period in our history, was large and energetic: around 10 kilometers in diameter, creating a 180 km wide, 20 km deep crater, letting out 2 million times the energy of the most powerful atomic bomb ever detonated.

Comet Swift-Tuttle, which crosses Earth’s orbit, is some 26 km in diameter, and moves incredibly fast by time it reaches Earth’s position. Not all comets and asteroids move at the same speed; in general, the farther away from the Sun you are when you’re at aphelion (your farthest point from the Sun), the faster you’ll be moving when you plunge through the inner Solar System. Swift-Tuttle gets far — farther away than Pluto is now — and by time it dives in past Earth, it not only moves at that 133,000 miles-per-hour figure we cited earlier, it has twenty-seven times as much kinetic energy as the impact that wiped out the dinosaurs. By many measures, this comet is the most dangerous object to Earth in our Solar System.

So the combination of the speed of this parent comet, the massive size of the parent comet, and the fact that it’s been engaged in this dance for thousands of years — having been recorded as early as 69 B.C.E. — means that its debris stream is relatively consistently spread out. The combination of these four factors:

- A wide debris stream, meaning the “good viewing” of the shower lasts for many days.

- A consistent debris stream, meaning you get “good viewing” every year,

- A fast motion with respect to Earth, meaning you get “bright” meteors,

- And a large nucleus to the comet, meaning there are lots of meteors to be seen,

is what makes the Perseids so spectacular.

There are three other showers (all mentioned above) that are spectacular in their own way, but none with the unique combination of the Perseids. Still, at their own time, they’re worth a watch.

The Quadrantids, peaking around January 3rd each year, are bright and numerous, but the debris stream is very, very narrow, meaning that the peak of the meteor shower lasts only for a few hours. For observers in the wrong part of the world, there’s nothing worth seeing at all; for observers in the right place at the right time, this one is as good as the Perseids.

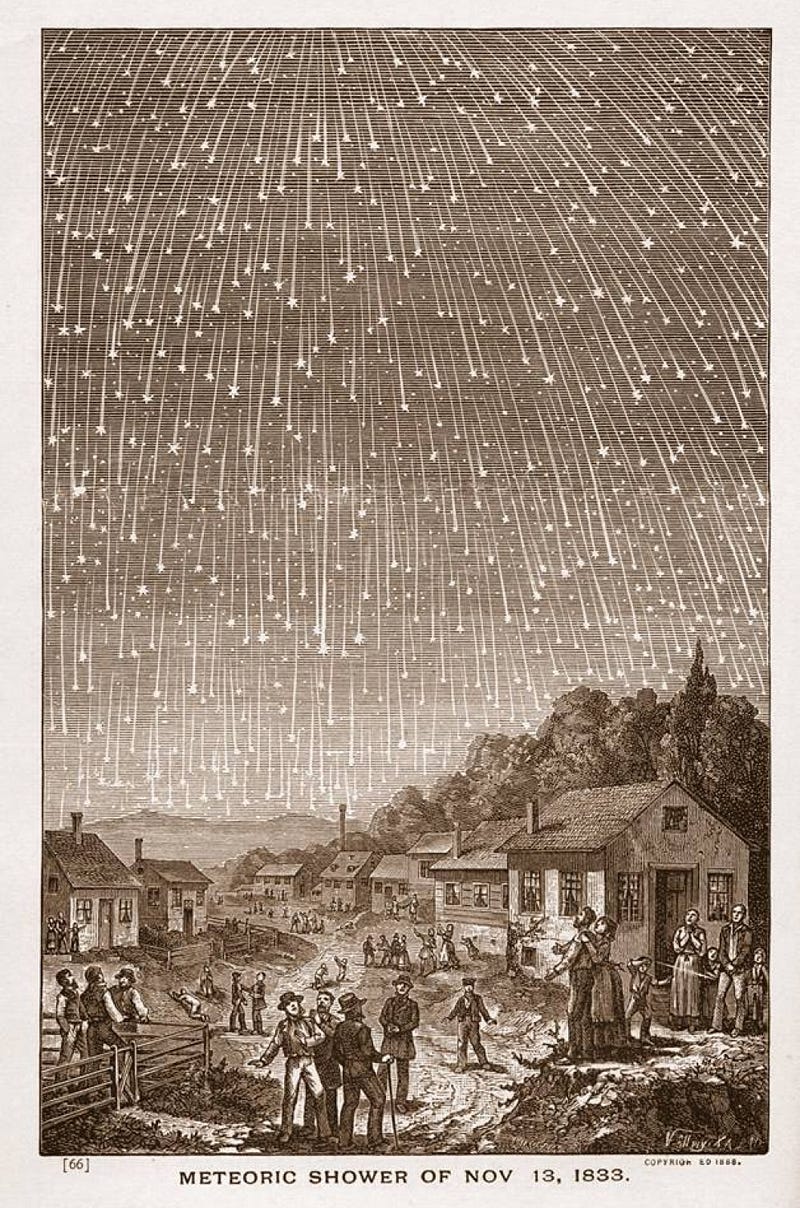

The Leonids are quiet most years, because the debris stream is very inconsistent. But this means every 33 years, including in 1833 (as illustrated above), we have a chance for a meteor storm, where you might see many hundreds or even upwards of 1000 meteors-per-hour. Come check on the Leonids around 2031 or so to see a chance at a legendarily spectacular show!

And the Geminids are sourced by an asteroid which orbits very rapidly. Over even the past few years, they’ve been increasing in intensity, becoming more and more spectacular every year, with greater meteor rates than even the Perseids, consistently. The only problem? With the debris stream moving as slowly as it does, these meteors are a lot dimmer than the ones you’ll see in August, meaning you’ll need darker skies to see any semblance of a good show at all.

When you go out to watch the Perseids this week (they peak tonight, the 12th/13th, although they’ll still be worth watching for until about Saturday night), keep in mind that the comet sourcing it last passed by in 1992. Even though the debris stream is fairly consistent, don’t be surprised if slowly, almost imperceptibly, the meteor shower itself gets weaker and less spectacular over the coming years and decades. By time we’re all old men and women, the Perseids will be at their low point, which may still make it the most spectacular & consistent annual show in the skies.

But it’s those four reasons — the debris stream’s width, consistency, the comet’s large nucleus and its elongated orbit — that combine to make the Perseids the most consistent, spectacular meteor shower of them all!

Leave your comments on our forum, and support Starts With A Bang on Patreon!