What Was It Like When Life In The Universe First Became Possible?

It took more than 9 billion years for Earth to form: the only known planet housing life. But it could have happened much, much sooner.

The cosmic story that unfolded following the Big Bang is ubiquitous no matter where you are. The formation of atomic nuclei, atoms, stars, galaxies, planets, complex molecules, and eventually life is a part of the shared history of everyone and everything in the Universe. As we understand it today, life on our world began, at the latest, only a few hundred million years after Earth was formed.

That puts life as we know it already nearly 10 billion years after the Big Bang. The Universe couldn’t have formed life from the very first moments; both the conditions and the ingredients were all wrong. But that doesn’t mean it took all those billions and billions of years of cosmic evolution to make life possible. It could have begun when the Universe was just a few percent of its current age. Here’s when life might have first arisen in our Universe.

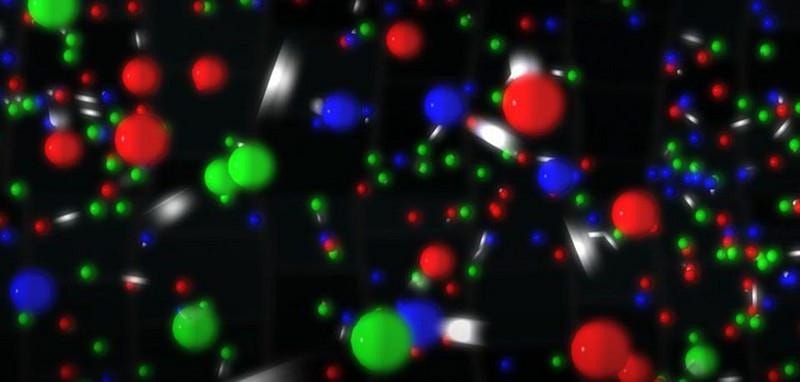

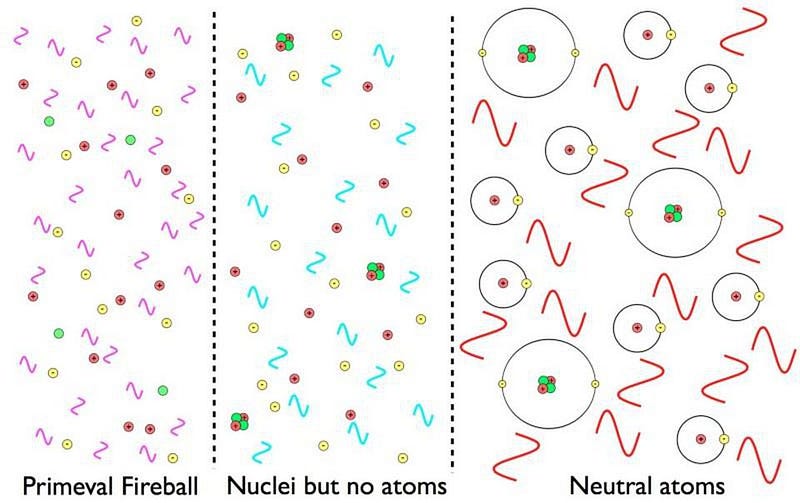

At the moment of the hot Big Bang, the raw ingredients for life could in no way stably exist. Particles, antiparticles, and radiation all zipped around at relativistic speeds, blasting apart any bound structures that might form by chance. As the Universe aged, though, it also expanded and cooled, reducing the kinetic energy of everything in it. Over time, antimatter annihilated away, stable atomic nuclei formed, and electrons could stably bind to them, forming the first neutral atoms in the Universe.

Yet these earliest atoms were only hydrogen and helium: insufficient for life. Heavier elements, such as carbon, nitrogen, oxygen and more, are required to build the molecules that all life processes rely on. For that, we need to form stars in great abundance, have them go through their life-and-death cycle, and return the products of their nuclear fusion to the interstellar medium.

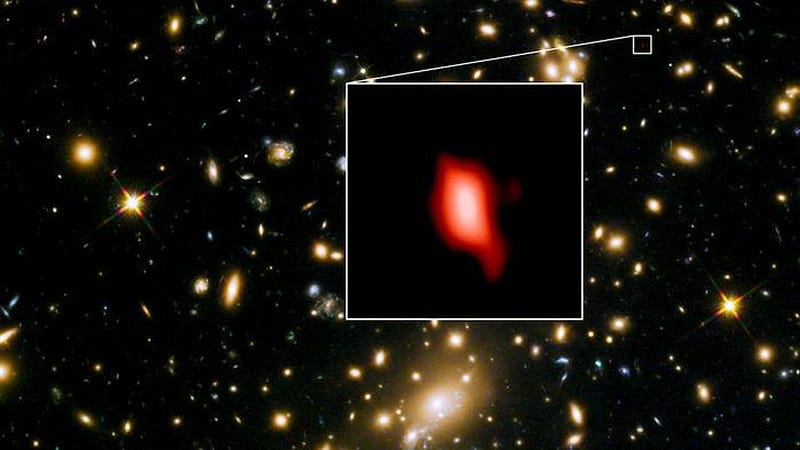

It takes 50-to-100 million years to form the first stars, sure, which form in relatively large clusters. But in the densest regions of space, these star clusters will gravitationally pull in other matter, including material for additional stars and other star clusters, paving the way for the first galaxies. By time only ~200-to-250 million years have passed, not only will multiple generations of stars have lived-and-died, but the earliest star clusters will have grown into galaxies.

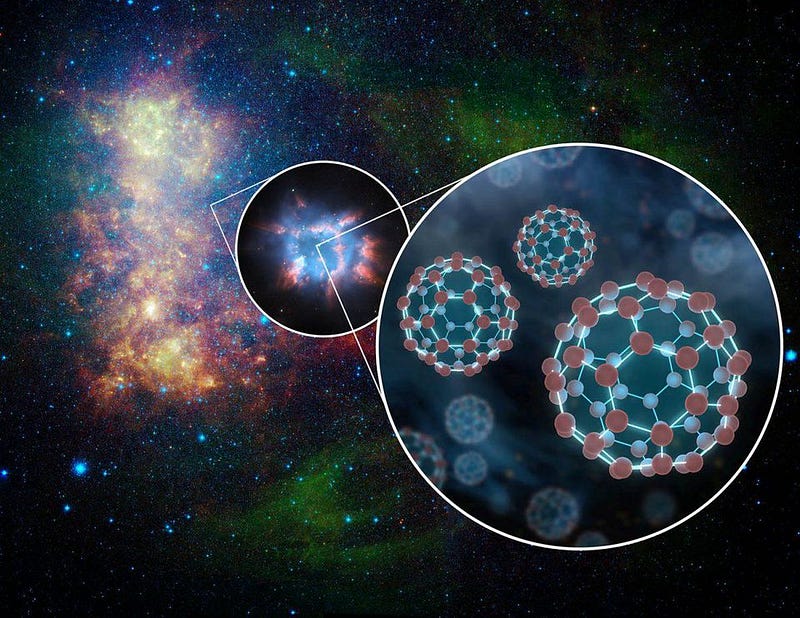

This is important, because we don’t just need to create the heavy elements like carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen; we need to create enough of them — and all of the life-essential elements — to produce a wide diversity of organic molecules.

We need those molecules to stably exist in a location where they can experience an energy gradient, such as on a rocky moon or planet in the vicinity of a star, or with enough undersea hydrothermal activity to support certain chemical reactions.

And we need for those locations to be stable enough that whatever counts as a life process can self-sustain.

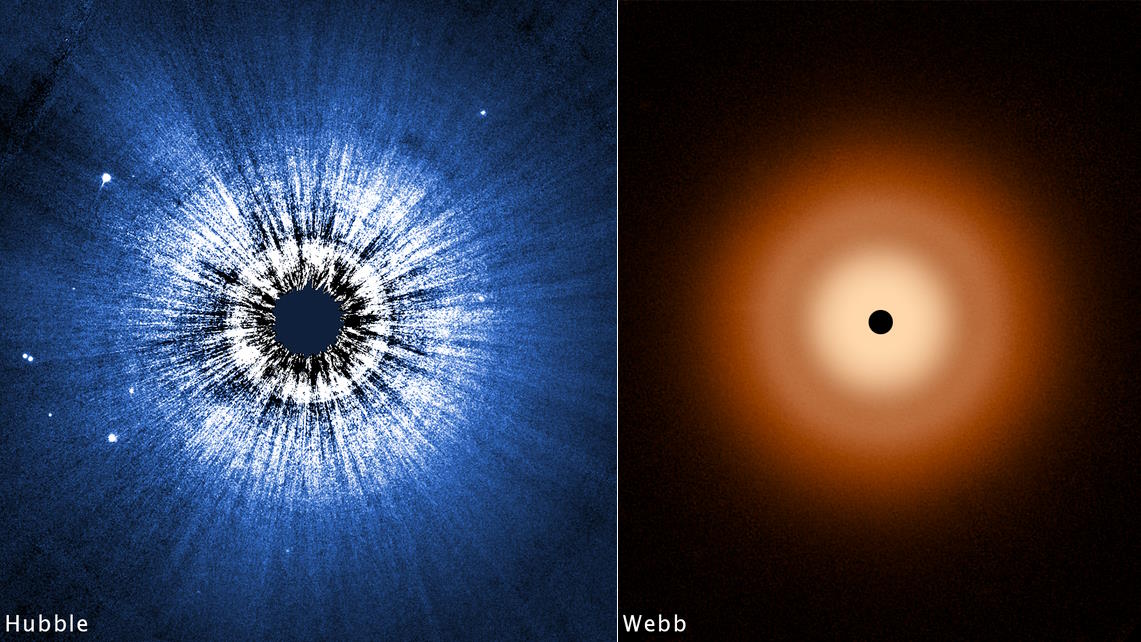

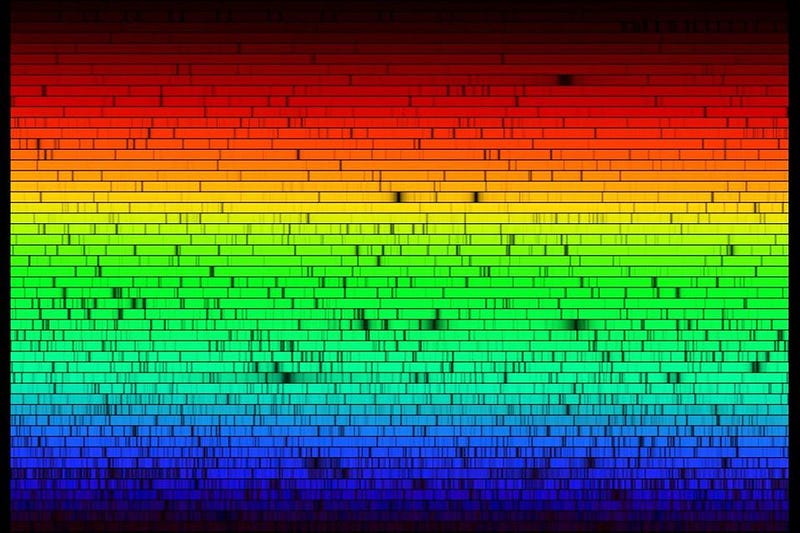

In astronomy, all of these conditions get lumped together by a single term: metals. When we look at a star, we can measure the strength of the different absorption lines coming from it, which tell us — in combination with the star’s temperature and ionization — what the abundances of the different elements are that went into creating it.

Add them all up, and that gives you the star’s metallicity, or the fraction of the elements within it that are heavier than either plain hydrogen or helium. Our Sun’s metallicity is somewhere between 1-and-2%, but that might be excessive for a requirement for life. Stars possessing just a fraction of that, perhaps as little as 10% the Sun’s heavy element content, might still have enough of the necessary ingredients, across-the-board, to make life possible.

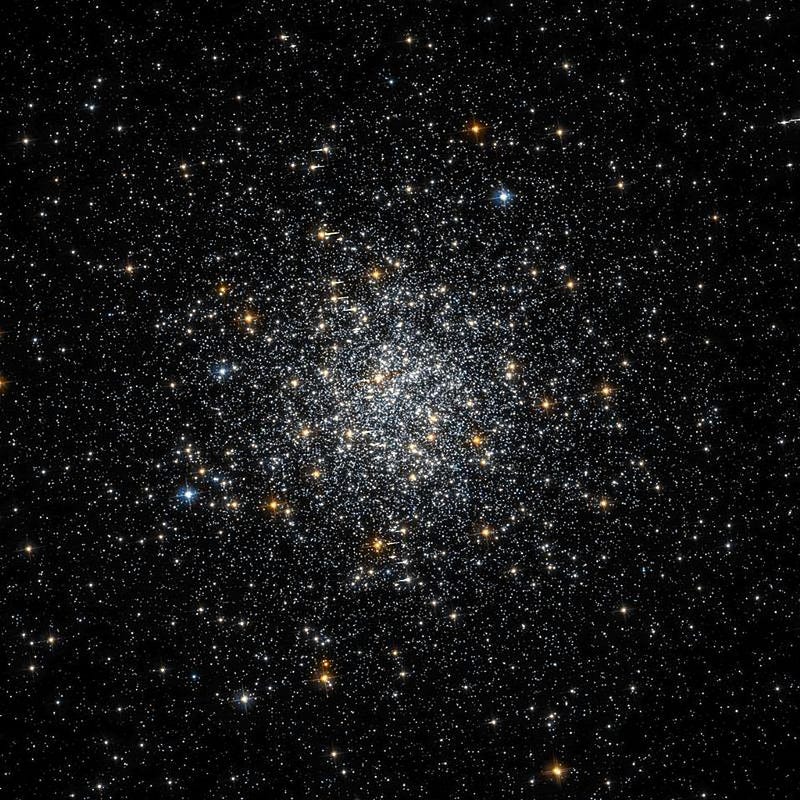

This gets really interesting, nearby, when we look at globular clusters. Globular clusters contain some of the oldest stars in the Universe, with many of them forming when the Universe was less than 10% its current age. They formed when a very massive cloud of gas collapsed, leading to stars that are all of the same age. Since a star’s lifetime is determined by its mass, we can look at the stars remaining in a globular cluster and determine its age.

For the more than 100 globular clusters in our Milky Way, most of them formed 12-to-13.4 billion years ago, which is extremely impressive considering the Big Bang was just 13.8 billion years ago. Most of the oldest ones, as you might expect, have just 2% of the heavy elements that our Sun has; they’re metal-poor and unsuited for life. But a few globular clusters, like Messier 69, offer a tremendous possibility.

Like most globular clusters, Messier 69 is old. It has no O-stars, no B-stars, no A-stars and no F-stars; the most massive stars remaining are comparable in mass to our Sun. Based on our observations, it appears to be 13.1 billion years old, meaning its stars come from just 700 million years after the Big Bang.

But its location is unusual. Most globular clusters are found in the halos of galaxies, but Messier 69 is a rare one found close to the galactic center: just 5,500 light-years away. (For comparison, our Sun is about 27,000 light-years from the galactic center.) This close proximity means that:

- more generations of stars have lived-and-died here than on the galaxy’s outskirts,

- more supernovae, neutron star mergers and gamma-ray bursts have occurred here than where we are,

- and, therefore, these stars should have a much greater abundance of heavy elements than other globular clusters.

And boy, does this globular cluster ever deliver! Despite its stars forming when the Universe was just 5% its present age, the close proximity to the galactic center means that the material its stars formed from were already polluted, and filled with heavy elements. When we deduce its metallicity today, even though these stars formed just a few hundred million years after the Big Bang, we find they have 22% the heavy elements that the Sun does.

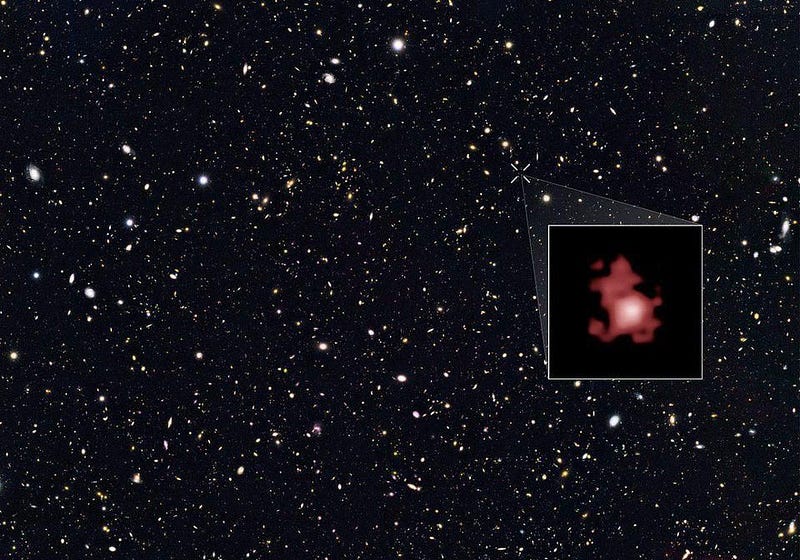

So that’s the recipe! Make many generations of stars quickly, form a planet resilient enough around one of the lower-mass, longer-lived stars (like a G-star or a K-star) to protect itself from whatever supernovae, gamma-ray bursts, or other cosmic catastrophes it may encounter, and let the ingredients do what they do. Whether we get lucky or not, there’s certainly an opportunity for life at the centers of the oldest galaxies we could ever hope to discover.

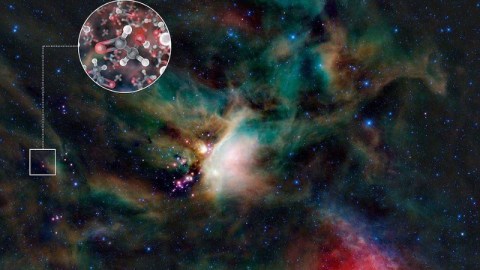

Wherever we look in space around the centers of galaxies, or around massive, newly forming stars, or in the environments where metal-rich gas is going to form future stars, we find a whole host of complex, organic molecules. These range from sugars to amino acids to ethyl formate (the molecule that gives raspberries their scent) to intricate aromatic hydrocarbons; we find molecules that are precursors to life. We only find them nearby, of course, but that’s because we don’t know how to look for individual molecular signatures much beyond our own galaxy.

But even when we look in our nearby neighborhood, we find some circumstantial evidence that life existed in the cosmos before Earth did. There’s even some interesting evidence that life on Earth didn’t even begin with Earth.

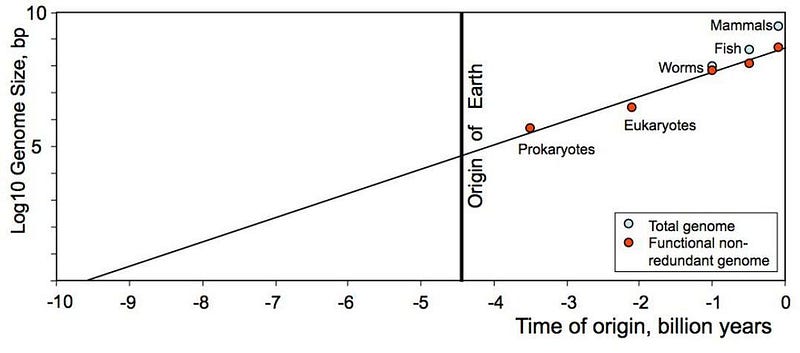

We still don’t know how life in the Universe got its start, or whether life as we know it is common, rare, or a once-in-a-Universe proposition. But we can be certain that life came about in our cosmos at least once, and that it was built out of the heavy elements made from previous generations of stars. If we look at how stars theoretically form in young star clusters and early galaxies, we could reach that abundance threshold after several hundred million years; all that remains is putting those atoms together in a favorable-to-life arrangement. If we form the molecules necessary for life and put them in an environment conducive to life arising from non-life, suddenly the emergence of biology could have come when the Universe was just a few percent of its current age. The earliest life in the Universe, we must conclude, could have been possible before it was even a billion years old.

Further reading on what the Universe was like when:

- What was it like when the Universe was inflating?

- What was it like when the Big Bang first began?

- What was it like when the Universe was at its hottest?

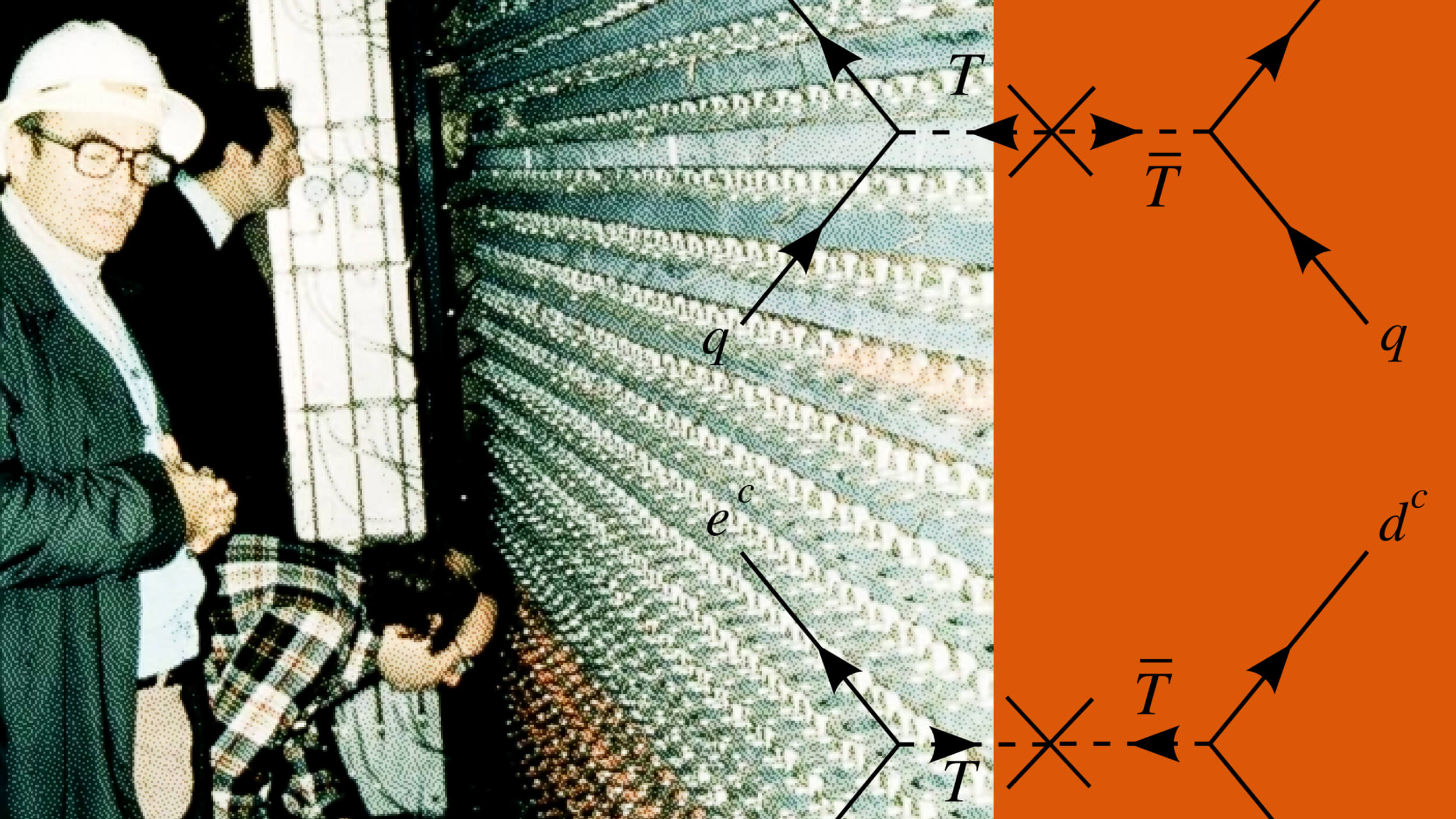

- What was it like when the Universe first created more matter than antimatter?

- What was it like when the Higgs gave mass to the Universe?

- What was it like when we first made protons and neutrons?

- What was it like when we lost the last of our antimatter?

- What was it like when the Universe made its first elements?

- What was it like when the Universe first made atoms?

- What was it like when there were no stars in the Universe?

- What was it like when the first stars began illuminating the Universe?

- What was it like when the first stars died?

- What was it like when the Universe made its second generation of stars?

- What was it like when the Universe made the very first galaxies?

- What was it like when starlight first broke through the Universe’s neutral atoms?

- What was it like when the first supermassive black holes formed?

- What was it like when life in the Universe first became possible?