What Scientific Arrogance Really Looks Like

The one thing that even the best of us do at times, and why it needs to stop.

“I will not let anyone walk through my mind with their dirty feet.”

–Mohandas Gandhi

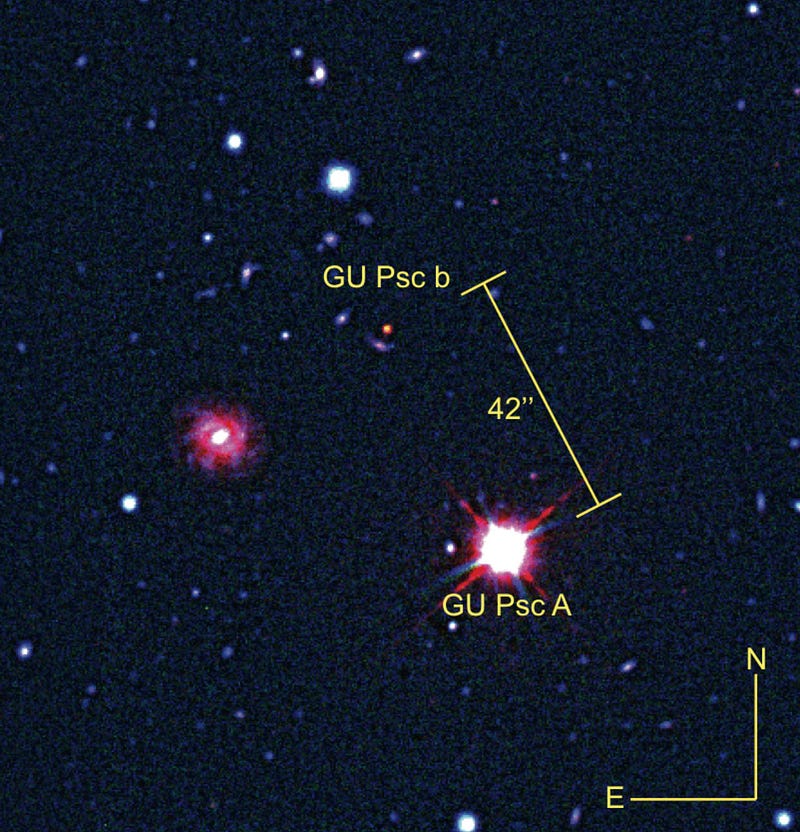

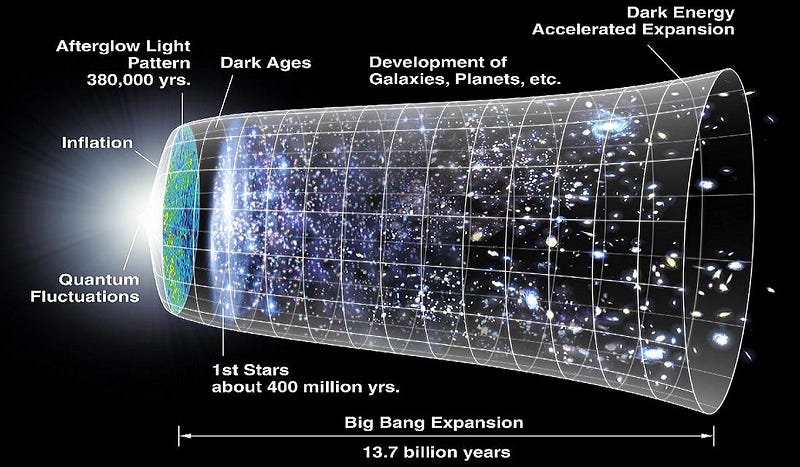

If there’s one thing that every person in this world should be both terrified of and delighted by, it’s the notion that — at any moment — new information could come to light that simply devastates the notions and preconceptions that you hold most dear. The star detective could discover DNA markings or fingerprints that completely exonerate the supposed serial killer he helped execute; the literary historian could find evidence that the work she’s devoted her life to was a forgery; the astrophysicist could discover a planetary system that quite clearly didn’t obey the supposedly universal laws of gravitation.

However difficult such a situation might be for the person forced to confront the ways they made sense of the world — and at some level, their value in it — the human enterprise advances because of our ability to do exactly that. Our ability to uncover new knowledge, assimilate it, and build a better world for ourselves with it is what enables us to advance as a species and as a society.

In all cases, new evidence can compel us to reevaluate even our most cherished, taken-for-granted and deeply ingrained assumptions about this Universe, at a scientific, historical, and even a personal level. But of all the different types of knowledge we have, scientific knowledge perhaps deserves to be the most valued of all.

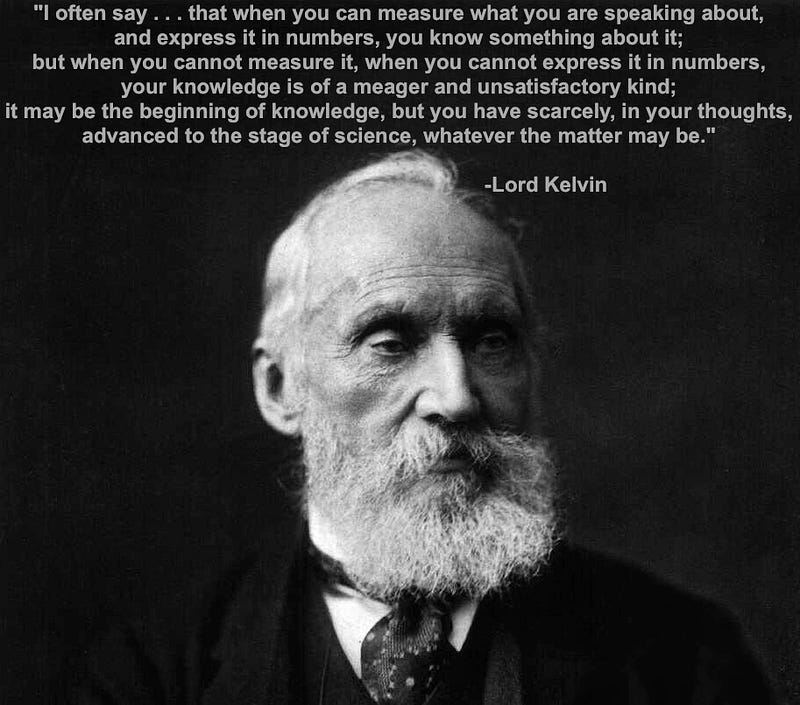

People often erroneously say that science isn’t a body of knowledge, but rather that it’s a process. The reason that’s erroneous is that science is both. There is a scientific process about collecting data in a controlled, reproducible-in-principle fashion that informs us about some phenomenon or set of phenomena in the natural world. We can use the data from not only that individual experiment but from the full suite of all well-controlled experiments and observations ever taken to infer laws, make and test hypotheses and eventually build overarching theories that explain as much of the phenomena as possible, and give us unparalleled predictive power as well as retrodictive power to model what will happen or should have happened in various physical scenarios.

And as we move from physical systems that can be modeled very simply (such as a single mass in empty space) to ones that are increasingly more complex, we quickly reach a point where using the most sound and fundamental tools to model a system become impractical, if not outright impossible. So scientifically, we make approximations, we simplify (and try not to oversimplify) models, we use perturbation theory and make simulations, and we uncover laws whose emergence from or relationship to the simpler systems that are at play is often unclear.

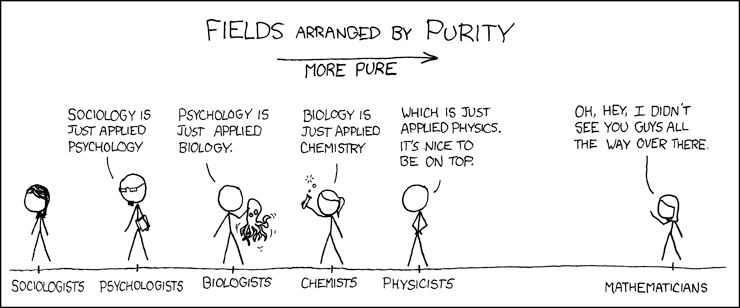

But let’s be clear about something: as long as we’re following the scientific process and adding to our scientific body of knowledge, we’re furthering our understanding of how the world works. That’s why I think it’s the height of arrogance — and foolishness — to engage in discussions, jests or (with apologies to xkcd) pissing contests like the one below.

Is it fair to say that sociology is applied psychology, that psychology is applied biology, that biology is applied chemistry, that chemistry is applied physics, that physics is applied mathematics, and — perhaps — that mathematics is applied philosophy? At some fundamental level it may be true, but almost never at a useful one. While it’s true that there are some laws that can be derived, or phenomena that will be seen to emerge, by starting with a fundamental sets of rules, the vast majority of knowledge we have about any field that can be scientifically examined is to examine it according to the scientific processes outlined above. You’re going to learn a lot more about biology performing biological experiments than you are by starting with protons, neutrons and electrons.

But the next time you’re tempted to make such a statement about a field that isn’t your own, ask yourself why you would say such a thing? Almost every time I’ve heard such a thing uttered, it’s been an incredibly disparaging and insulting thing to do, designed to put down someone’s legitimate (and often incredibly difficult, laborious and painstaking) work. If we’re all after the same goal — scientific truth — shouldn’t we respect the importance of one another’s work?

Especially considering how useless fundamental physics is for answering almost all questions related to chemistry, how useless chemistry is for answering questions about biology, biology about psychology, and psychology about sociology. Yes, biological systems obey the laws of physics, too, but quantum field theory has very little to say about the process of evolution; the process of science and what we learn from it needs people with all different motivations and interests if we want to maximize what we can learn about this Universe.

And that’s supremely important, considering all the pseudoscientists, quacks, shills, and false-knowledge purveyors out there.

There’s a fundamental difference between scientific knowledge — knowledge that was obtained through experiment and observation of real, verifiable and reproducible phenomena — and what I’ll just call unverified or unverifiable claims. The former is the best source of knowledge that we have; the latter is ignorance falsely posing as knowledge, perhaps the greatest enemy of knowledge humanity has ever known.

And yet, grappling with just what this knowledge means, what its limitations are, and what we can and cannot be certain about as far as reality is concerned is something that each of us must do on our own. Science doesn’t give us a blueprint for how to do it; it falls outside the scientific purview. For that, we need to turn to philosophy.

Now, philosophy doesn’t have the answers, but it does teach ways to consider the limits of our knowledge. And if you’re talking about the philosophy of science, so long as those doing the philosophizing are honestly and accurately representing the science (which is something they can only do if they actually understand it adequately themselves, which many — but not all — of them do), it can certainly give you a number of interesting possibilities to think about. Which is why I was incredibly disappointed to learn that Neil de Grasse Tyson went on the Nerdist Podcast, and absolutely ripped the entire field of philosophy as useless:

Neil de Grasse Tyson: [Philosophy] can really mess you up.

Interviewer: I always felt like maybe there was a little too much question asking in philosophy [of science]?

Neil de Grasse Tyson: I agree.

Interviewer: At a certain point it’s just futile.

Neil de Grasse Tyson: Yeah, yeah, exactly, exactly. My concern here is that the philosophers believe they are actually asking deep questions about nature. And to the scientist it’s, what are you doing? Why are you concerning yourself with the meaning of meaning?

Other interviewer: I think a healthy balance of both is good.

Neil de Grasse Tyson: Well, I’m still worried even about a healthy balance. Yeah, if you are distracted by your questions so that you can’t move forward, you are not being a productive contributor to our understanding of the natural world.

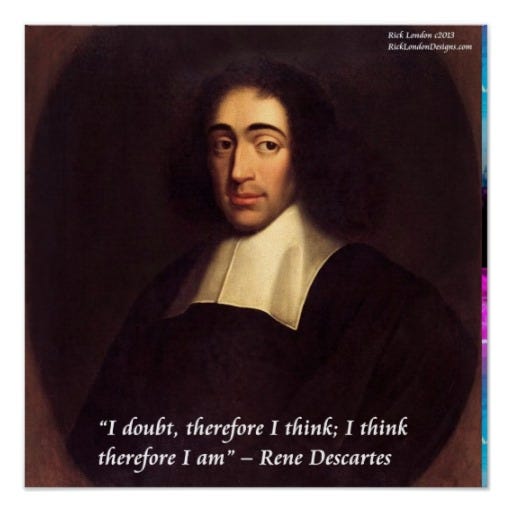

Massimo Pigliucci has some excellent thoughts on this (and so does Dan Fincke), but from a scientist’s perspective, I’d like to offer my wholehearted disagreement with Neil’s statements as well. You all remember Descartes (of Cartesian coordinates fame, mathematically) most famous statement:

It is true, of course, that there is no objective way to be sure that what we perceive or measure reality to be actually lines up with what reality actually is. But there is nothing wrong with wrestling with the concepts of solipsism, nor materialism, realism, idealism or other schools of philosophical thought.

Is there scientific knowledge to be gained from them? Probably not, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t a worthwhile endeavor to think about, particularly if it helps you to realize personal truths about yourself and how you deal with the world and Universe outside of your own mind. And there’s certainly nothing wrong with reminding ourselves of the assumptions we make inherent to all our endeavors in this Universe, whether they be scientific or not.

After all, the arts and humanities have a tremendous value to us as well, even if that isn’t scientific value. We may be long past the days where philosophers are going to herald a breakthrough in the natural sciences, but that doesn’t mean there isn’t value to philosophizing about them, or a great many other topics, for that matter.

Even if you have an insecurity about how important the thing you’re passionate about is, that’s no excuse to treat others like their passions are valueless simply because they aren’t yours. There’s nothing arrogant or inappropriate about saying, “this is what we know, scientifically” or “this is how we know it,” but so long as you’re not pretending to have knowledge that you don’t actually or legitimately possess, there’s nothing wrong with the pursuit of truth and its possibilities, even if we can never reach the ultimate destination.

Have a comment? Weigh in at the Starts With A Bang forum on Scienceblogs!