A science communicator’s 4 rules of persuasion

- The large amount of misinformation, disinformation, and loudly opinionated ignorance that’s out there makes the task of science communication more difficult than ever.

- Much of what passes for journalism these days falls into the trap of giving equal time, space, and weight to positions of vastly unequal merit; don’t fall for it.

- Even if it may not seem like it’s the case, the general public has a great craving to learn the truth. Here’s how you can tell it persuasively, without getting distracted by the noise.

In a world where it often seems like the loudest voices making the most outrageous claims have the greatest reach, sticking to telling the scientific truth can seem like a losing strategy. Much like Greek mythology’s Kassandra — given the gift of being able to foretell the future with 100% accuracy but simultaneously cursed so that no one would believe her — the arduous task of explaining what we know and how we know it in a scrupulous, responsible context should be rewarded, and yet it often feels like a strategy that’s punished. In a world where facts don’t matter and trust is non-existent, the most confidently-told lies and mistruths spread the fastest.

Anyone who’s ever tried to convince someone who holds a position that they simply cannot be reasoned out of is familiar with Brandolini’s Law: the effort involved in debunking misinformation is an order of magnitude greater than the effort involved in creating it. And yet, this is because the very act of debunking misinformation may well be the wrong strategy to take, as it not only gives unwarranted legitimacy to the illegitimate position itself, but falls for the trap of taking up the argument on an unequal, unfair playing field. If you want to argue for the scientific truth in a more persuasive manner, consider adopting these four rules of persuasion.

When it comes to communicating about any topic — scientific or otherwise — there are many different ways to successfully do it. Although everyone has their own style, it’s generally valuable to get to choose your own framework for the story you want to tell: setting it up in an honest, fair, and accessible way. When you consider who your audience is going to be, it’s generally a wise strategy to aim your message and communication strategy at the middle 80% of your audience: attempting to reach the greatest number of listeners with the most important aspects of the message you have to deliver.

It’s important to start at a “gettable” starting point: where you can be confident that your audience can begin on the same page as you, and then to continue adding new information slowly, one-step-at-a-time, as you gradually guide your audience down the line of thought you want them to follow. And then, when you arrive at your logical destination, emphasize where you are and how you got there for them, enabling them to not only follow along, but to see it and understand it for themselves. If you can follow that pathway, your audience will quite possibly take away the most important messages you sought to instill in them.

But this can be made difficult in a number of ways. Perhaps the most frequent way is that someone else has come along with a popular but flawed narrative, and that narrative has already gained a large amount of traction. We’ve seen this in many incarnations in recent years, from (completely unsupported by the evidence) claims that:

- the Earth is flat,

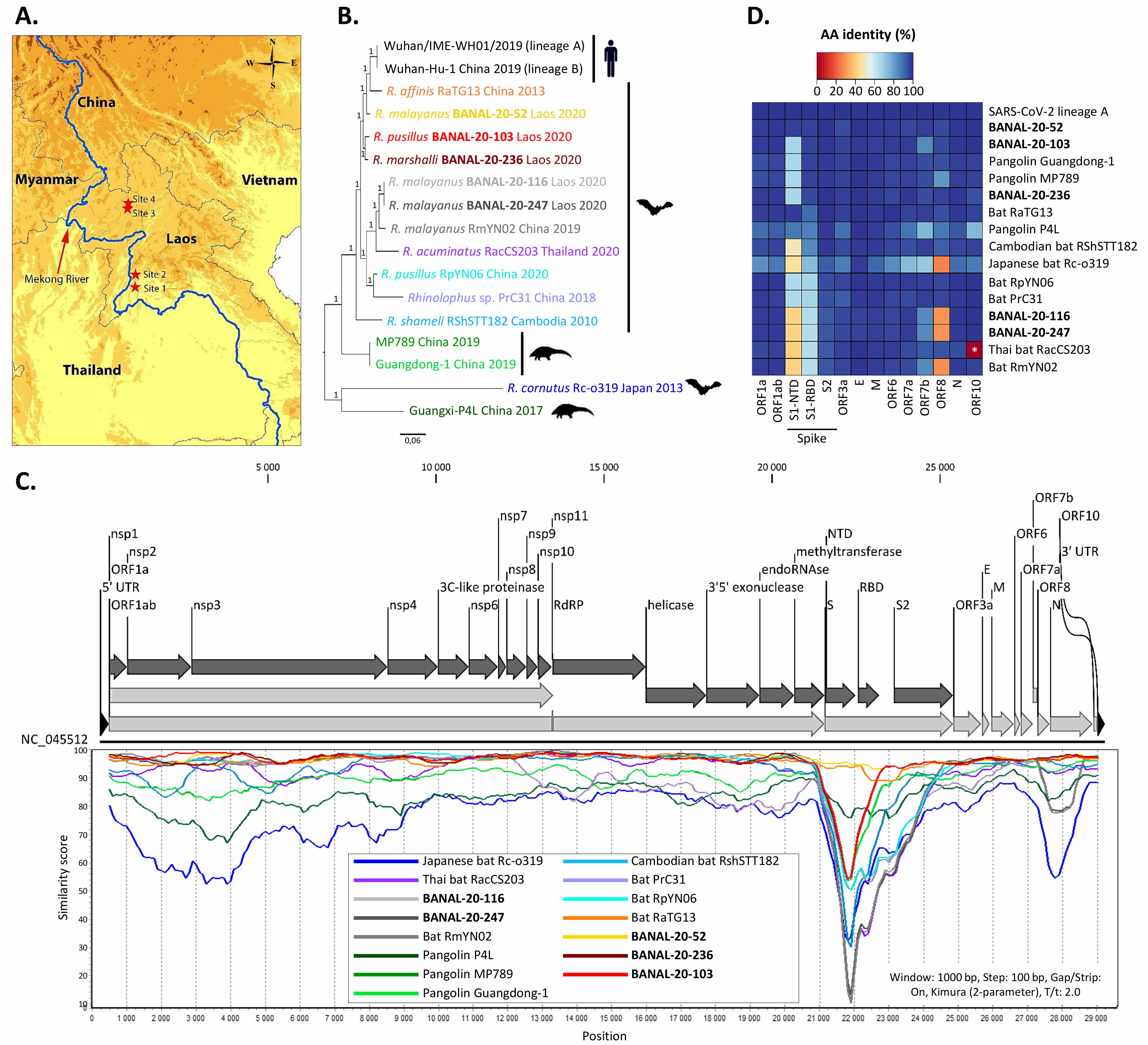

- the COVID-19 pandemic began from a genetically engineered virus in a Wuhan lab,

- mRNA vaccines alter your DNA,

- vaccines in general cause human magnetism,

- that 5G towers are bad for human health,

along with a host of other unsubstantiated accusations. Most of us, unless we’ve taken the time and expended the effort toward becoming a full-fledged expert in the particular area of science that the particular claim depends on, are completely unqualified to draw responsible conclusions. And yet, we all must inevitably decide for ourselves what we believe, who we trust, and what lines of reasoning we allow to convince us of a position. More troublingly, once we make up our minds, we’re very unlikely to change them; people tend to go with whatever their initial reactions were to any issue, scientific or otherwise, that arises.

And yet, there are those of us who pride ourselves on doing everything we can to gain the relevant expertise, do our homework to make sure our bases are covered and we haven’t missed any important points, and communicate the best understanding we have of what the truth is and how things work to a general audience. What are we to do when faced with frauds, charlatans, self-promoters, and others who are more interested in promoting a particular narrative than any adherence to the actual, provable, legitimate facts?

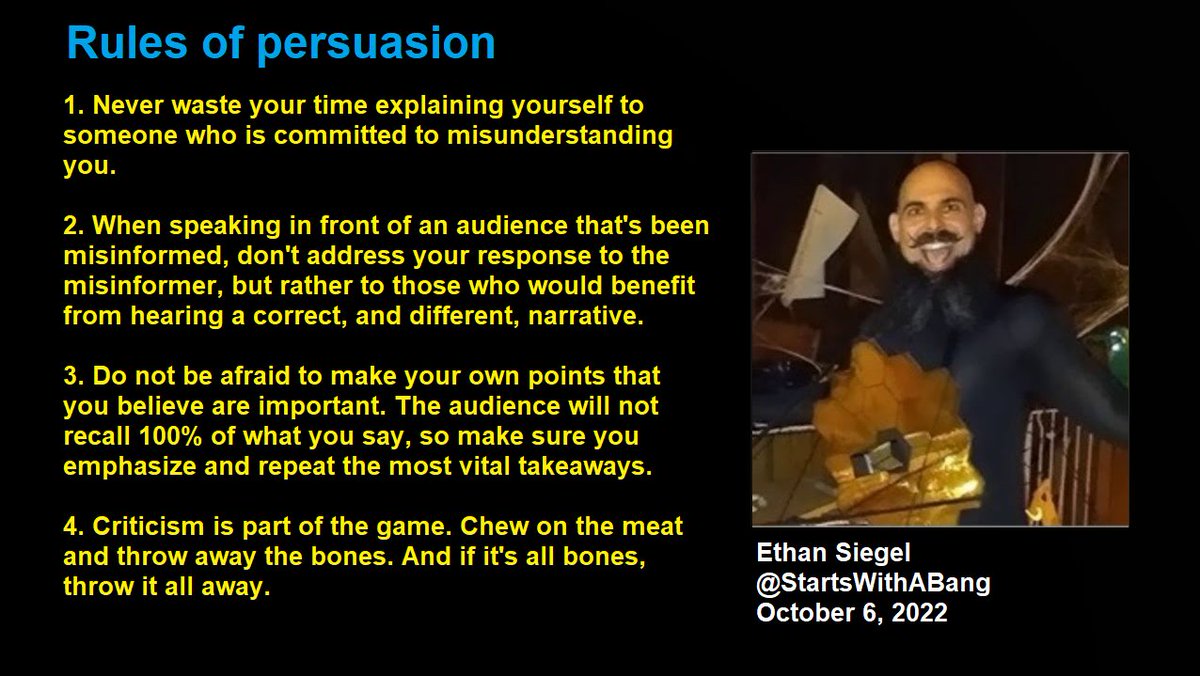

On October 6, 2022, I swiftly wrote out the following four rules for persuading others, intended for honest, scrupulous science communicators:

- Never waste your time explaining yourself to someone who is committed to misunderstanding you.

- When speaking in front of an audience that’s been misinformed, don’t address your response to the misinformer, but rather to those who would benefit from hearing a correct, and different, narrative.

- Do not be afraid to make your own points that you believe are important. The audience will not recall 100% of what you say, so make sure you emphasize and repeat the most vital takeaways.

- Criticism is part of the game. Chew on the meat and throw away the bones. And if it’s all bones, throw it all away.

Here’s how you can leverage these four rules to make your own compelling points, even when the prevailing narrative has no basis in reality at all.

Rule #1: Never waste your time explaining yourself to someone who is committed to misunderstanding you.

The most common type of “false claim” to potentially argue with is one where the claimant doesn’t care nearly as much about the facts or the logical progression of their argument as they do about reaching their preferred conclusion, or about sowing sufficient doubt about the conclusion they intend to reject. It’s up to you, based on your experience and intuition, to identify when someone is arguing in exactly that fashion: that is someone who’s fundamentally committed to misunderstanding you.

Don’t attempt to convince the person arguing with you that they are mistaken! You will not, you cannot, and your efforts will only lead to further frustration on your part.

Instead, work on assembling your arguments so that someone who encounters them will begin from a starting point where they will readily accept the facts you present, and then will be able to logically follow how one can use those facts to take steps that lead them to the inescapable conclusion that those facts indicate, whatever it may be. You are not going to convince the person who’s committed to misunderstanding you. But by crafting your own sound argument, and detailing that instead, you can help anyone committed to facts, logic, and reason to draw a more responsible conclusion. If you do it well, you may be even able to rescue those who’ve been led astray by the misinformer.

Rule #2: When speaking in front of an audience that’s been misinformed, don’t address your response to the misinformer, but rather to those who would benefit from hearing a correct, and different, narrative.

This is another important key. Being a science communicator is not like being a lawyer: it isn’t a case where the person making the most compelling argument “wins” by convincing others. Science communication, fundamentally, is about providing a window into the scientific process: where facts and measurements and observations and data lead us toward a set of conclusions. Regardless of what the misinformer says, this is the story you should be telling.

Tell your audience what the correct, scrupulous narrative is. Start at your own starting point: informed by the facts and where you estimate that ~80%+ of your audience will eagerly meet you. From there, introduce new information one piece at a time, and with each new piece, bring your audience along so that they can understand what footing you’re now on. In science, it isn’t “we believe” or “we think” or “we feel,” but rather “this is what the best data we have indicates,” and that’s something that everyone — regardless of what it is that they believe — can appreciate and benefit from. Science is for everyone, not just the people who think like you, look like you, or believe like you, so make the story about the science, not about you or the statements that have upset you.

Rule #3: Do not be afraid to make your own points that you believe are important. The audience will not recall 100% of what you say, so make sure you emphasize and repeat the most vital takeaways.

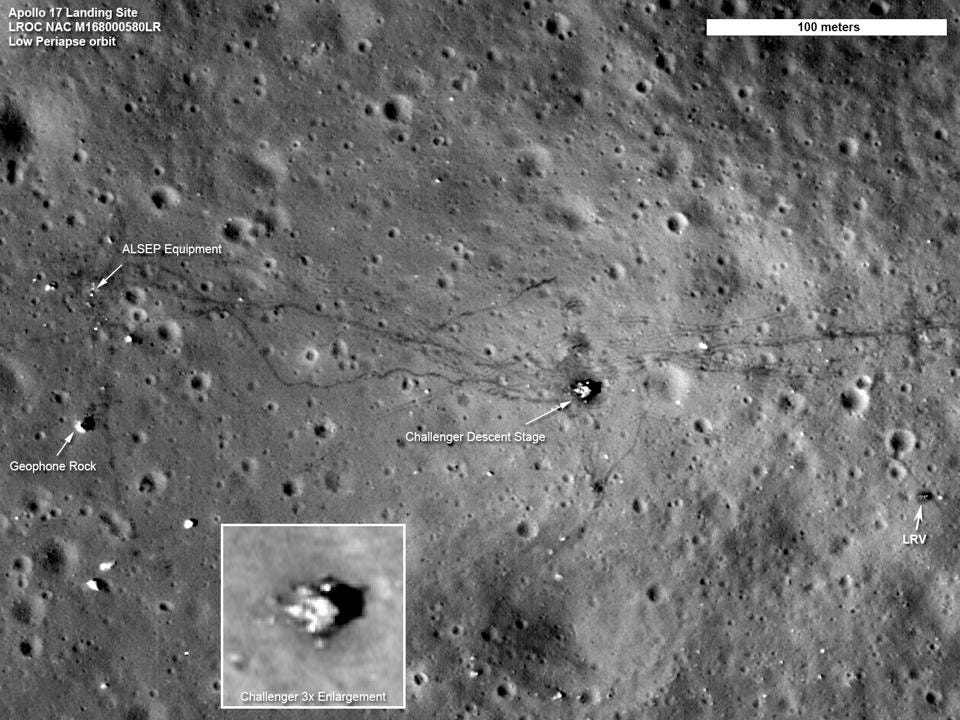

“But he said that shadows on the Moon show that it’s an example of stage lighting, not light emitted from the Sun!” Yes, there are many arguments that people pull out when they intend to argue against a demonstrable fact: such as the fact that human beings, beginning in the 1960s, have traveled in rockets that have taken us as far away as ~400,000 km from Earth, including to the Moon, where we’ve flown, orbited, and even landed, walked, and driven on the surface. Oftentimes, however, the arguments are made where the data and evidence is the weakest, and spending your time addressing them is valuable time you could be making your own, strong, valid points.

Arguing against whatever baseless, bogus claims someone is making is perhaps the worst way to try and convince readers, listeners, and onlookers of which position is correct. Instead, put forth the strongest evidence you have — the evidence that, if you were a completely dispassionate observer, would lead you to draw an unambiguous conclusion — and let your audience draw their own conclusions based on that evidence. Some people will go through whatever mental gymnastics they can think of, including taking illogical steps, to deny whatever aspect of reality they’ve decided is antithetical to their core identity. Don’t fall into that trap; simply tell the truth and present the good, compelling evidence. That will be enough.

And rule #4: Criticism is part of the game. Chew on the meat and throw away the bones. And if it’s all bones, throw it all away.

As a reward for all of this hard work, what do you think the response you’ll get will be? There will be a few people who will agree with you, praise you, and tell you what a good, important, and necessary job you did. But far and away, the overwhelming majority of feedback you’re going to get will be negative. Particularly if it’s a famous, polarizing figure with a zealous fanbase who made the claims you’re attempting to counter, you can expect abuse, ridicule, threats, and potentially even violence.

You must be open to criticism, however, because sometimes the criticism you receive will, in fact, be legitimate. Sometimes you will — no matter how great your expertise — discover that you’ve made a mistake somewhere. You have to be open to that criticism because you must demonstrate a willingness to learn and revise what you previously thought based on new information that you didn’t have previously. There are many legitimate experts in any field, and sometimes, they (or even non-experts who’ve effectively listened to them) will have valuable things to say that can improve your own arguments and understanding. But sometimes, the criticism will be entirely invalid. In those cases, don’t be afraid to throw it all away; it’s the only responsible thing to do when that situation arises.

One of the things you must remember is this: everyone is entitled to their own opinion, but while some opinions are nuanced and others have some justifiable aspects to them, some opinions truly have only negative value. Sometimes, an opinion is just someone’s outlet for their own pent-up frustrations and wrath, and sometimes that wrath is not even properly directed, but spills over into adjacent, innocent areas. You do not gain anything by returning fire in that salvo; it only serves to elevate the profile of the one doing damage with their opinions.

But by following these rules — by speaking around the misinformation and crafting your own truthful, meaningful narrative instead — you can often overcome many of the cognitive biases that someone would otherwise possess. Remember, one of the most difficult things for anyone to ever admit to themselves is, “I was wrong.” If you’re approaching someone who’s been infected with misinformation, or even worse, the misinformer themselves, hoping to get them to say, “I was wrong,” you’ve already begun the conversation at a tremendous disadvantage. Odds are, they’re only going to dig into their entrenched position more deeply, simply ignoring or glossing over your most compelling, convincing points.

But if you can craft your own story that simply exposes people to the truth, without triggering their intellectual defense mechanisms, you can compel them to develop a new line of thought in their minds: one that enables them to consider a possibility they might otherwise be closed-off to. People don’t often say, “I strongly believe this thing, now let me fairly consider the opposite.” However, they do often say, “You know, I feel strongly about this one thing, but I also feel strongly about this other thing, and now I realize those two things may be in conflict. Is there some way I can resolve this inside of myself?”

That’s the hope. That’s your best strategy for persuading the misinformed. Craft your own narrative. Begin at a starting point that’s agreeable and inoffensive. Add pieces of information that are verifiably true and slowly build up your own case until you reach your scrupulous conclusion. Tailor your messaging style to the audience you’re attempting to address. And then, once you’ve arrived at your intellectual destination, remind your audience of what you’ve concluded and how you arrived there. If you receive criticism, consider its content and also consider the source: whatever part of it is valid, use it to refine and strengthen your argument further.

But don’t get caught up in the illegitimate criticism you’ll receive from contrarians, crackpots, and those with fringe beliefs. Remember, in science communication, just like in video games, when you find yourself encountering new enemies, that’s a sign that you’re moving in the right direction.