Messier Monday: The Butterfly Cluster, M6

The farther north you are, the harder this wonder is to see. But oh, the rewarding sights for those who find it!

Image credit: Emi; Ivamov, via http://www.emilivanov.com/CCD%20Images/M06_LRGB.htm.

“Happiness is a butterfly, which when pursued, is always just beyond your grasp, but which, if you will sit down quietly, may alight upon you.”

–Nathaniel Hawthorne

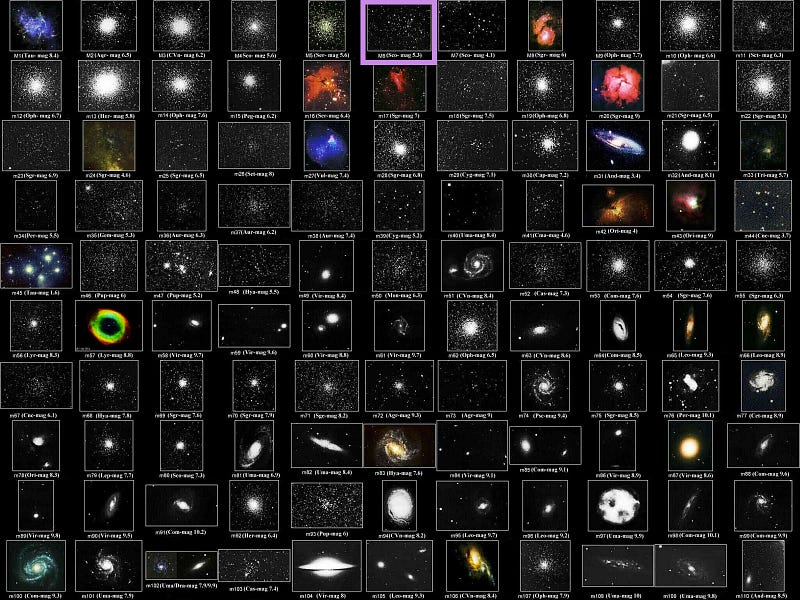

Back in the 1700s, comet-hunters faced a daunting challenge: how to search for potential new discoveries without getting distracted by the fixed objects that appeared in their telescopes. To that end, Charles Messier set out to catalogue the various clusters and nebulae that were easily visible up in the night sky, creating the first comprehensive catalogue of bright, deep-sky objects. The catalogue’s 110 objects stands as a monument to his efforts, and today they represent some of the best sights the night sky has to offer!

Each Monday, we’ve been taking an in-depth look at once of these objects, seeing both how it appears through a variety of views and telling the scientific story of what’s going on inside of it. Many of these objects are actually located well south of the celestial equator, and the current season — from July through September — offer the best (and in some cases, the only) views of these deep-sky wonders.

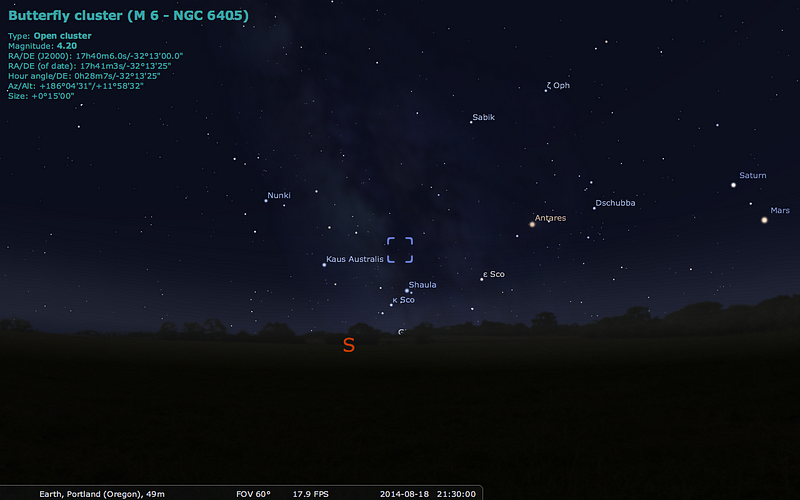

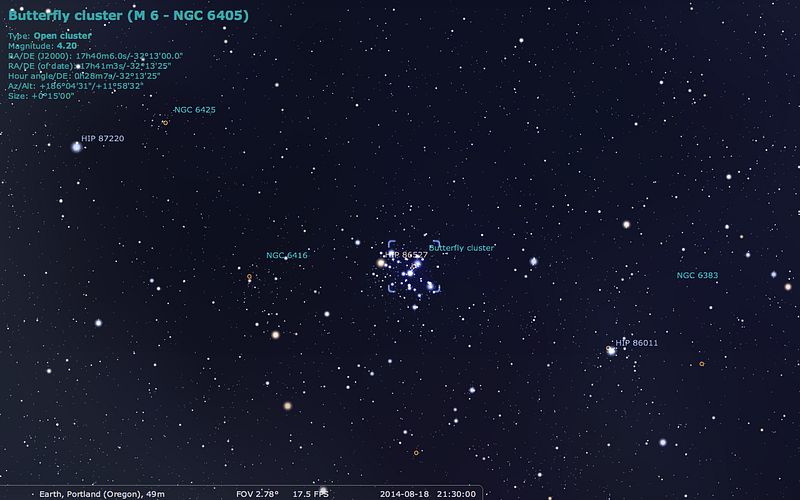

Today’s treat is one of the most southerly star clusters in the entire catalogue: Messier 6, the Butterfly Cluster. Here’s how to find it.

Once the sky darkens after sunset, look towards the south, where the constellations of Scorpius and Sagittarius reign supreme. Scorpio is home to the brilliant red giant, Antares, while Sagittarius contains the very bright teapot asterism, both clearly identifiable in the early part of the night.

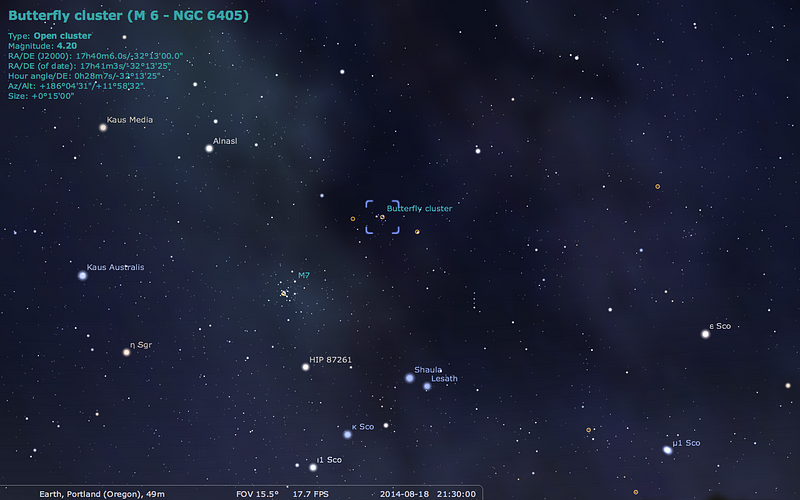

Just beyond the “nose” of the teapot (the star Alnasl), and just north of the second-brightest star in Scorpius, Shaula, you can find two Messier star clusters close together: Messier 7 (the most southerly of all Messier objects), larger and a little farther southeast, and today’s object, Messier 6, a little higher in the sky and farther to the northwest.

There aren’t any brilliant stars to guide you there beyond the ones you see above, but if you follow the top of the “spout” of the teapot, from Kaus Media to Alnasl and beyond, you’ll run into a clearly-visible naked eye star, HIP 87220.

Continue onwards about another 1.5°, and you won’t be able to miss Messier 6, heralded by a bright orange giant (often visible to the naked eye) against a backdrop of fainter, bluer stars.

Through even a small, low-powered telescope (or a pair of binoculars), this cluster puts on a brilliant show.

Discovered all the way back in the 1650s (and possibly even as early as Ptolemy), Messier added this to his catalogue as one of the first objects back in 1764, writing:

“Cluster of small stars between the bow of Sagittarius & the tail of Scorpius. At simple view [to the naked eye], this cluster seems to form a nebula without stars; but even with the smallest instrument one employs for investigating one sees a cluster of small [faint] stars.”

The orange one may be the brightest, but even a small amount of magnification shows the others shining brilliantly alongside it.

Messier often described stars as “small,” meaning faint, indicating that they appeared small and low-in-brightness in the optics of his own telescope. But these stars are only faint as seen from Earth; in reality, they’re huge and brilliant, even compared to our own Sun!

What you’re looking at here is a very young cluster of stars that’s relatively nearby, located in the plane of our galaxy towards the very center. The brilliant orange-tinted stars are giants; having burned through their core’s hydrogen, they’ve moved on to helium, destined to end their lives in short order in a planetary nebula, with their core contracting down to a white dwarf. On the other hand, the blue stars (as well as all the other cluster members not a part of the galactic background) are quite young, at slightly under 100 million years, and thought to be somewhere between two-and-eight times as massive as our own Sun.

We can tell what age a star cluster is by looking at the brightnesses and colors of the stars that are there, and inferring what stars must have burned out by now. In the case of Messier 6 — known as the Butterfly Cluster because of it’s very rough resemblence to the eponymous insect — there are no O-class stars remaining, and no B-class stars brighter than class B4 (where 0 is the brightest/bluest and 9 is the dimmest/reddest), telling us that those stars have all burned through their fuel and died by now.

Since those stars are the shortest-lived, we can infer an age of 51-to-95 million years from the ones remaining!

There’s a small amount of dust (or ‘nebulosity’) left here, which should continue to burn away as the hot, ultraviolet radiation exerts enough pressure to drive this material back out into the interstellar medium. It’s even conceivable that what we’re seeing is not dust intrinsic to the cluster itself, but simply dust that’s part of outer space that happens to be passing through the cluster.

At a distance of only 1,600 light-years from Earth, this is one of the brightest star clusters visible from our world!

To those of you further south, the cluster rises higher in the sky, and will appear even more brilliant and spectacular, as there’s less atmosphere to contend with. At just six light-years in radius, at such a close distance, there were actually eighty individual members of this cluster identified as long ago as the 1950s.

Of course, using modern telescope and CCD (charged-coupled-device) camera technology, dedicated amateurs can identify literally hundreds of stars in this region of space. Have a look at this masterpiece by Jim Misti,

which clearly shows that for every bright, easily-identifiable “blue” star in this cluster — and remember, the blue stars are the hottest, brightest and least numerous stars — there are many others that are white, yellow or red, and much dimmer! And because this cluster is so close to us, even the amazing image above only encapsulates about a quarter of the cluster. Even though it has never been observed by Hubble, it’s hard to ask for a better photo than the one you see above!

And with that, we’ll come to the end of another Messier Monday! Including this one, we’ve taken a look at the following Messier objects:

- M1, The Crab Nebula: October 22, 2012

- M2, Messier’s First Globular Cluster: June 17, 2013

- M3, Messier’s First Original Discovery: February 17, 2014

- M4, A Cinco de Mayo Special: May 5, 2014

- M5, A Hyper-Smooth Globular Cluster: May 20, 2013

- M6, The Butterfly Cluster: August 18, 2014

- M7, The Most Southerly Messier Object: July 8, 2013

- M8, The Lagoon Nebula: November 5, 2012

- M9, A Globular from the Galactic Center: July 7, 2014

- M10, A Perfect Ten on the Celestial Equator: May 12, 2014

- M11, The Wild Duck Cluster: September 9, 2013

- M12, The Top-Heavy Gumball Globular: August 26, 2013

- M13, The Great Globular Cluster in Hercules: December 31, 2012

- M14, The Overlooked Globular: June 9, 2014

- M15, An Ancient Globular Cluster: November 12, 2012

- M18, A Well-Hidden, Young Star Cluster: August 5, 2013

- M20, The Youngest Star-Forming Region, The Trifid Nebula: May 6, 2013

- M21, A Baby Open Cluster in the Galactic Plane: June 24, 2013

- M23, A Cluster That Stands Out From The Galaxy: July 14, 2014

- M24, The Most Curious Object of All: August 4, 2014

- M25, A Dusty Open Cluster for Everyone: April 8, 2013

- M27, The Dumbbell Nebula: June 23, 2014

- M29, A Young Open Cluster in the Summer Triangle: June 3, 2013

- M30, A Straggling Globular Cluster: November 26, 2012

- M31, Andromeda, the Object that Opened Up the Universe: September 2, 2013

- M32, The Smallest Messier Galaxy: November 4, 2013

- M33, The Triangulum Galaxy: February 25, 2013

- M34, A Bright, Close Delight of the Winter Skies: October 14, 2013

- M36, A High-Flying Cluster in the Winter Skies: November 18, 2013

- M37, A Rich Open Star Cluster: December 3, 2012

- M38, A Real-Life Pi-in-the-Sky Cluster: April 29, 2013

- M39, The Closest Messier Original: November 11, 2013

- M40, Messier’s Greatest Mistake: April 1, 2013

- M41, The Dog Star’s Secret Neighbor: January 7, 2013

- M42, The Great Orion Nebula: February 3, 2014

- M44, The Beehive Cluster / Praesepe: December 24, 2012

- M45, The Pleiades: October 29, 2012

- M46, The ‘Little Sister’ Cluster: December 23, 2013

- M47, A Big, Blue, Bright Baby Cluster: December 16, 2013

- M48, A Lost-and-Found Star Cluster: February 11, 2013

- M49, Virgo’s Brightest Galaxy: March 3, 2014

- M50, Brilliant Stars for a Winter’s Night: December 2, 2013

- M51, The Whirlpool Galaxy: April 15th, 2013

- M52, A Star Cluster on the Bubble: March 4, 2013

- M53, The Most Northern Galactic Globular: February 18, 2013

- M56, The Methuselah of Messier Objects: August 12, 2013

- M57, The Ring Nebula: July 1, 2013

- M58, The Farthest Messier Object (for now): April 7, 2014

- M59, An Elliptical Rotating Wrongly: April 28, 2014

- M60, The Gateway Galaxy to Virgo: February 4, 2013

- M61, A Star-Forming Spiral: April 14, 2014

- M62, The Galaxy’s First Globular With A Black Hole: August 11, 2014

- M63, The Sunflower Galaxy: January 6, 2014

- M64, The Black Eye Galaxy: February 24, 2014

- M65, The First Messier Supernova of 2013: March 25, 2013

- M66, The King of the Leo Triplet: January 27, 2014

- M67, Messier’s Oldest Open Cluster: January 14, 2013

- M68, The Wrong-Way Globular Cluster: March 17, 2014

- M71, A Very Unusual Globular Cluster: July 15, 2013

- M72, A Diffuse, Distant Globular at the End-of-the-Marathon: March 18, 2013

- M73, A Four-Star Controversy Resolved: October 21, 2013

- M74, The Phantom Galaxy at the Beginning-of-the-Marathon: March 11, 2013

- M75, The Most Concentrated Messier Globular: September 23, 2013

- M77, A Secretly Active Spiral Galaxy: October 7, 2013

- M78, A Reflection Nebula: December 10, 2012

- M79, A Cluster Beyond Our Galaxy: November 25, 2013

- M80, A Southern Sky Surprise: June 30, 2014

- M81, Bode’s Galaxy: November 19, 2012

- M82, The Cigar Galaxy: May 13, 2013

- M83, The Southern Pinwheel Galaxy, January 21, 2013

- M84, The Galaxy at the Head-of-the-Chain, May 26, 2014

- M85, The Most Northern Member of the Virgo Cluster, February 10, 2014

- M86, The Most Blueshifted Messier Object, June 10, 2013

- M87, The Biggest One of them All, March 31, 2014

- M88, A Perfectly Calm Spiral in a Gravitational Storm, March 24, 2014

- M89, The Most Perfect Elliptical, July 21, 2014

- M90, The Better-You-Look, The Better-It-Gets Galaxy, May 19, 2014

- M91, A Spectacular Solstice Spiral, June 16, 2014

- M92, The Second Greatest Globular in Hercules, April 22, 2013

- M93, Messier’s Last Original Open Cluster, January 13, 2014

- M94, A double-ringed mystery galaxy, August 19, 2013

- M95, A Barred Spiral Eye Gazing At Us, January 20, 2014

- M96, A Galactic Highlight to Ring in the New Year, December 30, 2013

- M97, The Owl Nebula, January 28, 2013

- M98, A Spiral Sliver Headed Our Way, March 10, 2014

- M99, The Great Pinwheel of Virgo, July 29, 2013

- M100, Virgo’s Final Galaxy, July 28, 2014

- M101, The Pinwheel Galaxy, October 28, 2013

- M102, A Great Galactic Controversy: December 17, 2012

- M103, The Last ‘Original’ Object: September 16, 2013

- M104, The Sombrero Galaxy: May 27, 2013

- M105, A Most Unusual Elliptical: April 21, 2014

- M106, A Spiral with an Active Black Hole: December 9, 2013

- M107, The Globular that Almost Didn’t Make it: June 2, 2014

- M108, A Galactic Sliver in the Big Dipper: July 22, 2013

- M109, The Farthest Messier Spiral: September 30, 2013

With only 14 objects to go, including open clusters, globular clusters, star-forming nebulae, with a planetary nebula and a galaxy left, which one will be next? Come back next week to find out, only here on Messier Monday!

Leave your comments at the Starts With A Bang forum on Scienceblogs!