How Traveling Back In Time Could Really, Physically Be Possible

And you don’t even need a Delorean at 88 MPH.

It’s one of the greatest tropes in movies, literature, and television shows: the idea that we could travel back in time to alter the past. From the time turner in Harry Potter to Back To The Future to Groundhog Day, traveling back in time provides us with the possibility of righting wrongs in our own past. To most people, it’s an idea that’s relegated to the realm of fiction, as every law of physics indicates that motion forward through time is an absolute necessity. Philosophically, there’s also a famous paradox that seems to indicate the absurdity of such a possibility: if traveling backwards through time were possible, you’d be able to go back and kill your grandfather before your parents were ever conceived, rendering your own existence impossible. For a long time, there seemed to be no way to go back. But thanks to some very interesting properties of space and time in Einstein’s General Relativity, traveling back in time may be possible after all.

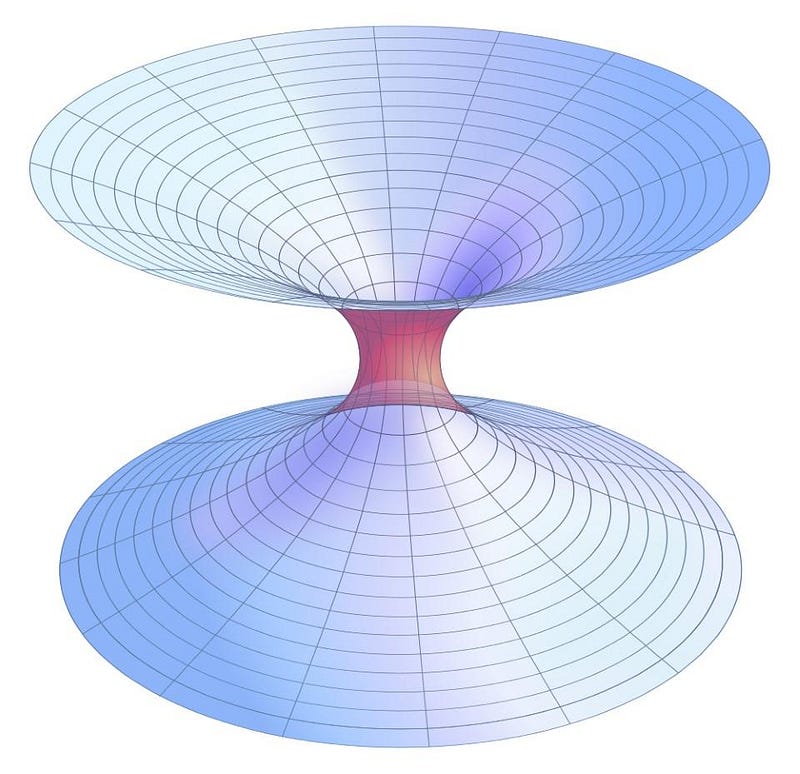

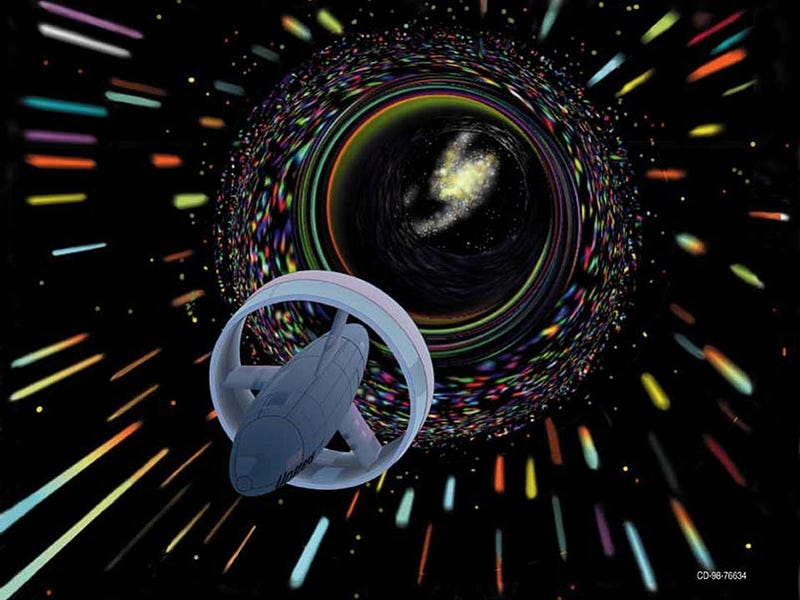

The place to start is with the physical idea of a wormhole. In our known Universe, we have tiny, minuscule quantum fluctuations in the fabric of spacetime on the smallest of scales. These include energy fluctuations in both the positive and negative directions, often very close by one another. A very strong, dense, positive energy fluctuation would create curved space in one particular fashion, while a strong, dense, negative energy fluctuation would curve space in exactly the opposite fashion. If you connected these two curvature regions together, you could — for a brief instant — arrive at the notion of a quantum wormhole. If the wormhole lasted for long enough, you could even potentially transport a particle through it, allowing it to instantly disappear from one location in spacetime and reappear in another.

If we want to scale that up, however, to allow something like a human being through, that’s going to take some work. While every known particle in our Universe has positive energy and either positive or zero mass, it’s eminently possible to have negative mass/energy particles in the framework of General Relativity. Sure, we haven’t discovered any yet, but according to all the rules of theoretical physics, there’s nothing forbidding it.

If this negative mass/energy matter exists, then creating both a supermassive black hole and the negative mass/energy counterpart to it, while then connecting them, should allow for a traversible wormhole. No matter how far apart you took these two connected objects from one another, if they had enough mass/energy — of both the positive and negative kind — this instantaneous connection would remain. All of that is great for instantaneous travel through space. But what about time? Here’s where the laws of special relativity come in.

If you travel close to the speed of light, you experience a phenomenon known as time dilation. Your motion through space and your motion through time are related by the speed of light: the greater your motion through space, the less your motion through time. Imagine you had a destination that was 40 light years away, and you were able to travel at incredibly high speeds: over 99.9% the speed of light. If you got into a spaceship and traveled very close to the speed of light towards that star, then stopped, turned around, and returned back to Earth, you’d find something odd.

Due to time dilation and length contraction, you might reach your destination in only a year, and then come back in just another year. But back on Earth, 82 years would have passed. Everyone you know would have aged tremendously. This is the standard way time travel physically works: it takes you into the future, with the amount of travel forward in time dependent only on your motion through space.

But if you construct a wormhole like we just described, the story changes. Imaging one end of the wormhole remains close to motionless, such as remaining close to Earth, while the other one goes off on a relativistic journey close to the speed of light. You then enter the rapidly-moving end of the wormhole after it’s been in motion for perhaps a year. What happens?

Well, a year isn’t the same for everyone, particularly if they’re moving through time and space differently! If we talk about the same speeds as we did earlier, the “in motion” end of the wormhole would have aged 40 years, but the “at rest” end would only have aged by 1 year. Step into the relativistic end of the wormhole, and you arrive back on Earth only one year after the wormhole was created, while you yourself may have had 40 years of time to pass.

If, 40 years ago, someone had created such a pair of entangled wormholes and sent them off on this journey, it would be possible to step into one of them today, in 2017, and wind up back in time at the mouth of the other one… back in 1978. The only issue is that you yourself couldn’t also have been at that location back in 1978; you needed to be with the other end of the wormhole, or traveling through space to try and catch up with it.

Satisfyingly, we discover that this form of time travel also forbids the grandfather paradox! Even if the wormhole were created before your parents were conceived, there’s no way for you to exist at the other end of the wormhole early enough to go back and find your grandfather prior to that critical moment. The best you can do is to put your newborn father and mother on a ship to catch the other end of the wormhole, have them live, age, conceive you, and then send yourself back through the wormhole. You’ll be able to meet your grandfather when he’s still very young — perhaps even younger than you are now — but it will still, by necessity, occur at a moment in time after your parents were born.

A great many unusual things become possible in the Universe if negative mass/energy is real, abundant, and controllable, but traveling backwards in time might be the wildest one we’ve ever imagined. Owing to the oddities of both special and general relativity, time travel to the past might not be forbidden after all!

Ethan Siegel is the author of Beyond the Galaxy and Treknology. You can pre-order his third book, currently in development: the Encyclopaedia Cosmologica.