Why Einstein’s E = mc² is only half of the equation

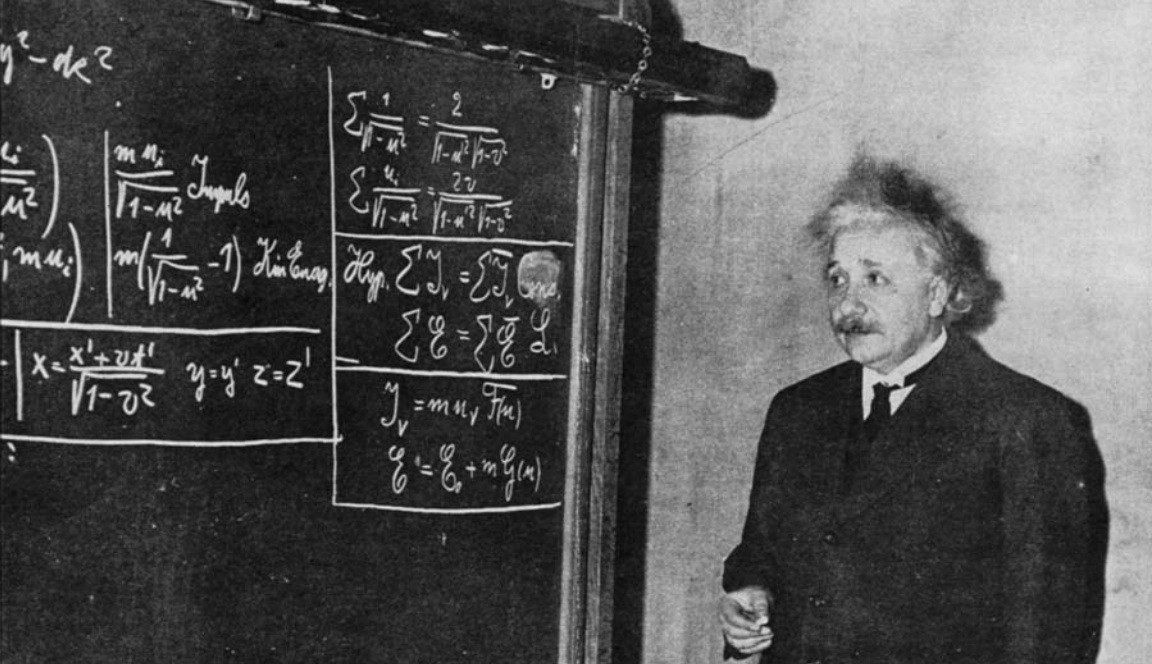

- First introduced way back in 1905, Einstein’s most famous equation, E = mc², put forth the mathematical formula relating energy to the amount of rest mass inherent to an object.

- Over time, the equation came to describe particle-antiparticle creation and annihilation, the energy released from nuclear fusion and fission reactions, and much more.

- But E = mc² only describes the “rest mass energy” of massive particles. If your particles are in motion or have no rest mass at all, the other half of the story is absolutely essential.

One of the most profound insights to come about in all of physics has been what’s easily Einstein’s most famous equation: E = mc². Quite simply, it states that energy is equal to an object’s mass multiplied by the speed of light squared. This simple-seeming mathematical relation holds an enormous amount of physics inside of it, including:

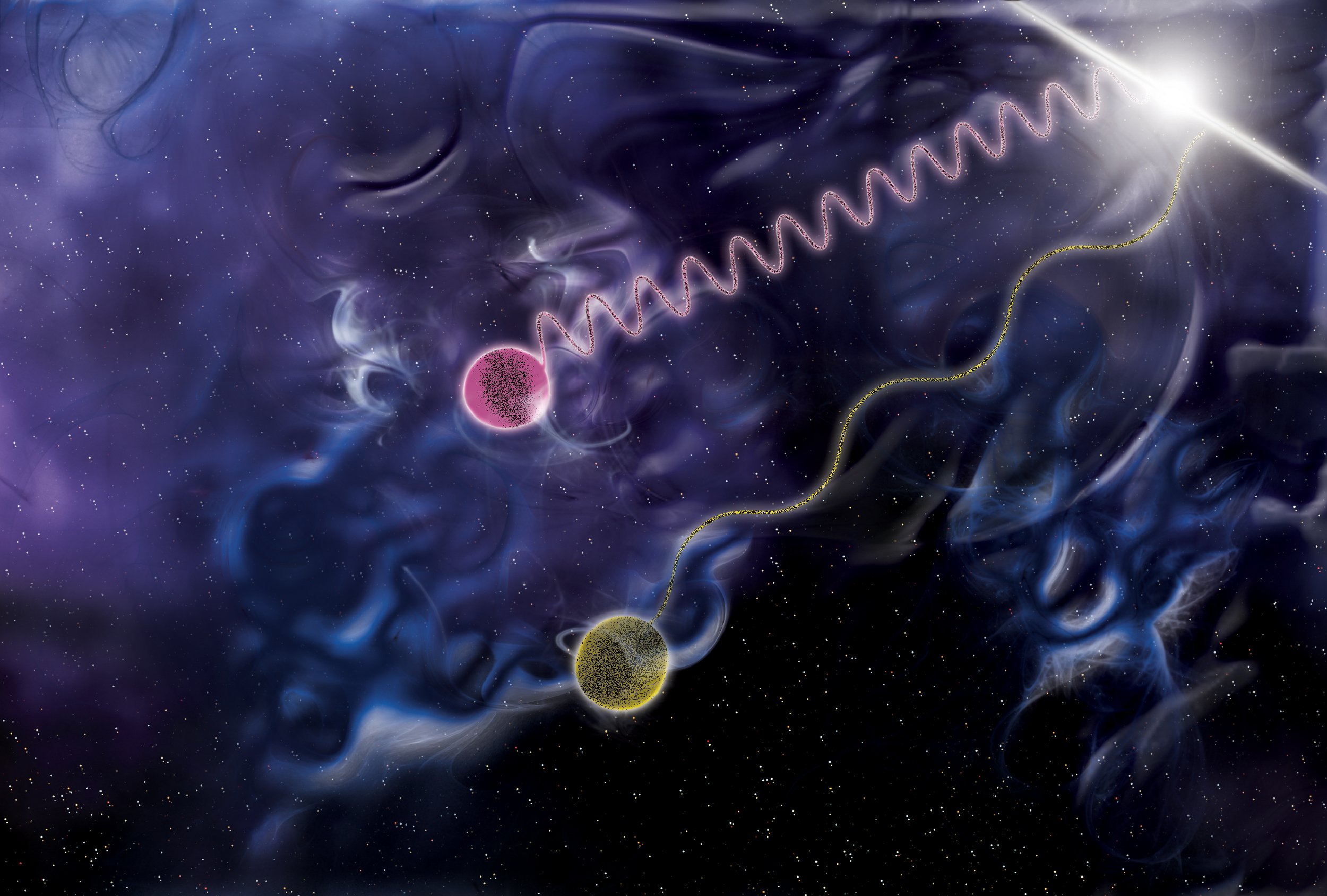

- if you have a certain amount of energy available, you can spontaneously create new matter-antimatter pairs of particles as long as their rest mass is less than the amount of energy required to create them,

- if a matter-antimatter pair of particles annihilates, they will produce a specific amount of energy given by the masses of the pair of particles that annihilated,

- and that every time you have a nuclear reaction, whether fusion or fission, if the mass of the products is less than the mass of the reactants, E = mc² tells you how much energy will be liberated in that reaction.

This one equation, E = mc², describes how much energy is inherent to any massive particle at rest, including how much energy it takes to create it and how much energy is released if you destroy it.

But what if your particle isn’t at rest, or what if it doesn’t have any mass at all? In those cases, E = mc² is only half of the meaningful equation. The other half is far more interesting, and is required to make physical sense of what’s going on.

The reason “rest mass” is such an important concept is because motion — the rate of change of an object’s position over time — isn’t an “absolute” physical property in our Universe. Instead, the key lesson from Einstein’s relativity is that irrespective of what your position is or how your position is changing with time, the laws of physics and the constants of nature, including the speed of light, are always going to appear to be the same.

So if, for example, you have a clock where “one second” is defined by how long it takes light, moving at the speed of light, to:

- rise from the bottom of the clock to the top,

- reflect off of a mirror at the top,

- and come back down to the bottom once again,

then two observers in relative motion to one another will experience the passage of time differently. From the perspective of one observer, they’re the ones at rest, and their definition of a “second” is the correct one: a round-trip for that light, to go from the bottom to the top to the bottom of the clock, that defines their passage through time. For anyone in motion relative to them, that additional motion means that those external, moving clocks appear to run slow.

The reason for this is that motion through space and time are connected and inextricable: woven together into a fabric known as spacetime. The maximum “motion through time” you can possess is what you experience when you’re at rest with respect to the Universe, or when your motion through space is zero. If you do move through space, however, your motion through time slows, which is why the closer you move to the speed of light, the less you age and experience the passage of time. This has a myriad of applications, from global positioning systems (GPS) to high-energy particle physics.

But this is where we have to look at another part of Einstein’s E = mc²: when you’re in motion, your energy isn’t just given by your rest-mass energy, which is the mc² contribution to your energy. Instead, you also have kinetic energy: the energy of motion itself.

Whenever two objects collide, whether they stick together (inelastically) or bounce off of one another (elastically), it’s the kinetic energy that they possess, based on their motion relative to one another, that determines how fast they’ll each wind up moving after they crash into each other. This “energy of motion,” or kinetic energy, is essential to the physics of objects in motion, from billiard balls to automobiles to planetary systems.

But you’ll notice that Einstein’s most famous equation, E = mc², has absolutely no dependence on motion at all! If energy is simply mass multiplied by the speed of light squared, then how does motion factor into this? Where does kinetic energy come from?

Perhaps an even more compelling argument that there must be more to the story becomes apparent if we consider light: a quantum of energy that has no rest mass at all. Light, whether we treat it as a wave whose energy is defined by its wavelength or a particle whose energy is quantized into packets known as photons, has no rest mass, so the m in E = mc² has to equal zero. But light carries energy, so E = mc² can’t be all that there is, or E would equal zero, too, which it cannot.

There’s a hint toward the solution if you took physics in High School or college, and learned about the “standard” formula for kinetic energy: KE = ½mv², where v is the speed of the object in motion. This formula only applies at speeds that are low compared to the speed of light: where v is much smaller than c, the speed of light in a vacuum. (That’s the same “c” that’s in E = mc²: 299,792,458 m/s.)

The reason that “kinetic energy” offers such a useful hint is because it leads you one step closer to the real key concept in completing Einstein’s most famous equation: momentum.

Momentum is the “quantity of motion” that an object has, and it’s well-defined whether the thing that’s in motion is massive or massless, and, if massive, whether it moves close to the speed of light or not. Momentum, labeled with a p for very Latin reasons — arising either from the verb “pellere” (to push forcefully) or “petere” (to go) — is basically a measure of how much “Ooomph!” an object has to its motion, and consequently, how difficult it is to bring it to rest.

- For massive particles moving slow compared to the speed of light, momentum can be well-approximated by the simple formula p = mv.

- For massive particles moving at any speed, even at a substantial fraction of the speed of light, momentum is more precisely written p = mγv, where “γ” is the Lorentz factor: 1/√(1-(v/c)²).

- And for massless particles, like light, that move at the speed of light and have no rest mass at all, momentum can’t be written in terms of mass, but can be written in terms of energy very simply, as p = E/c.

If we want to give the true expression for the energy inherent to any particle, then, we need to include the effects of its quantity of motion on energy as well as its rest mass’s effects on energy. E = mc², as simple, compact, and notorious as it is, only applies to massive particles at rest: a useful quantity only in certain cases.

Fortunately, there’s an almost-as-simple formula that incorporates both the rest mass energy of a particle, when present, along with the contribution of its quantity of motion to energy as well. That formula for energy is as follows:

E = √(m²c⁴ + p²c²)

Think about what happens in all the different cases that apply here. If momentum (p) is zero, then that last term goes away entirely, and you simply get E = √(m²c⁴), which just becomes good old E = mc² once again: Einstein’s original rest mass-energy equivalence equation.

What if we’re moving slow compared to the speed of light, and we just put in p = mv for momentum?

Then the equation becomes E = √(m²c⁴ + m²v²c²), or, if we pull out an mc² from inside the square root,

E = mc² * √(1 + (v/c)²).

This might not look particularly familiar to you, but consider the following: this equation only works for values of speed, or v, that are slow compared to the speed of light, or c in this equation.

Therefore, the part of the equation that reads √(1 + (v/c)²) is only going to be a little bit greater than one, because the (v/c) term is small. Whenever you have, in mathematics, an expression that’s √(1 + x), wherever “x” is small compared to 1, it can be excellently approximated by 1 + ½*x.

If we do that to our expression for energy, we turn √(1 + (v/c)²) into 1 + ½*(v/c)², which turns our expression for energy into

E = mc² * (1 + ½*(v/c)²),

which becomes, when we multiply the terms out:

E = mc² + ½mv²,

which tells us that the total energy is the rest mass energy (the mc² part) plus the kinetic energy (the ½mv² part).

When we have a massive particle that moves close to the speed of light, however, we can no longer make any such approximations with any sort of reliability; you simply have to calculate the full thing for yourself, using the equation E = √(m²c⁴ + p²c²).

But as you get to very high momentums, which is precisely the case that we deal with in our largest and most powerful particle accelerators, the rest mass term contributes very little to the overall energy. At 99.999%+ the speed of light, the m²c⁴ term will be much smaller than the p²c² term in the equation, which means we can neglect it.

If we do, then we simply get E = √(p²c²), which becomes E = pc: the equation for the energy-momentum relationship for photons and other massless particles. We sometimes call this the ultra-relativistic approximation, as it’s useful wherever the rest mass energy of a system is small compared to the energy due to motion; we can neglect that first term — the m²c⁴ term — even if the object moving ultra-relativistically isn’t truly massless.

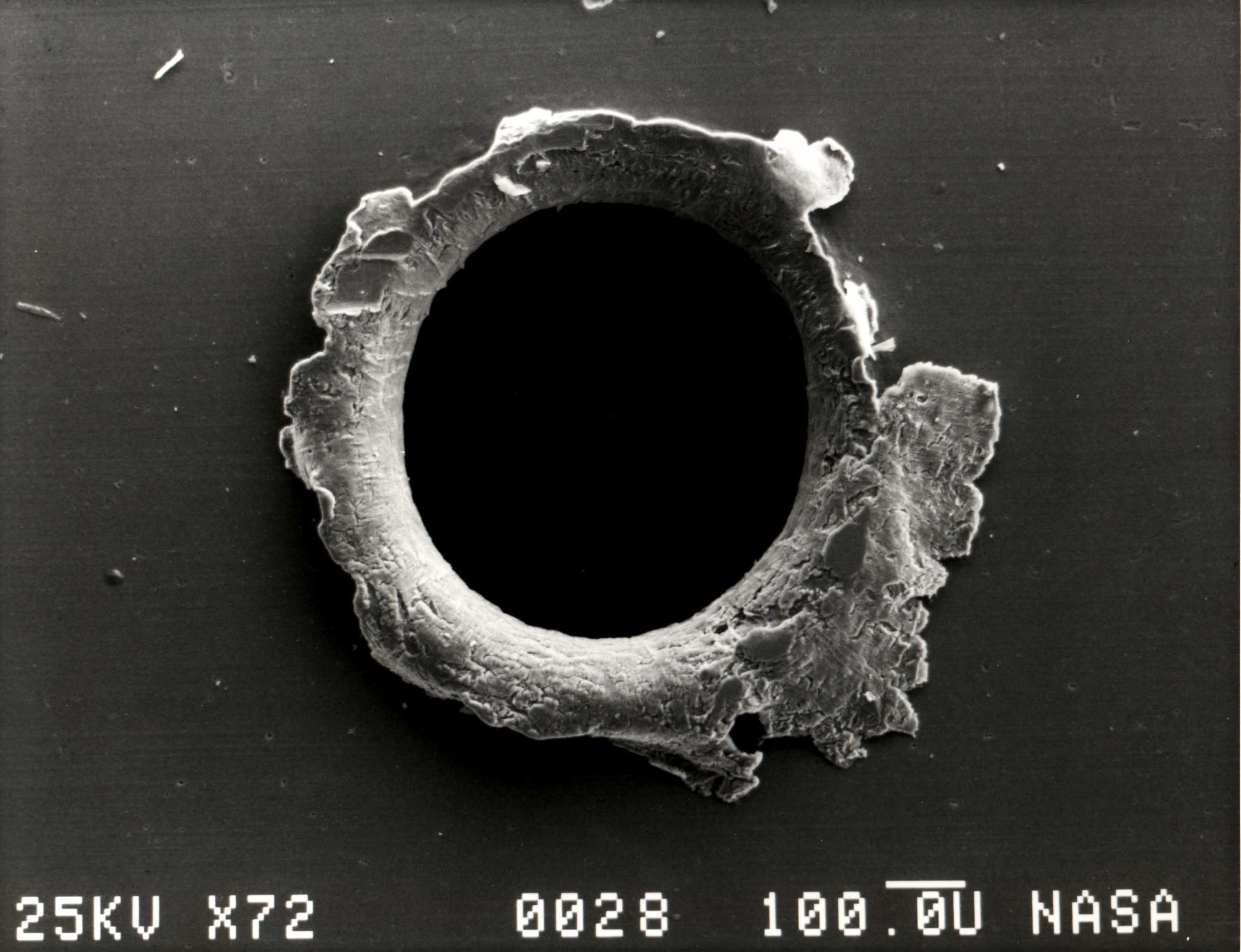

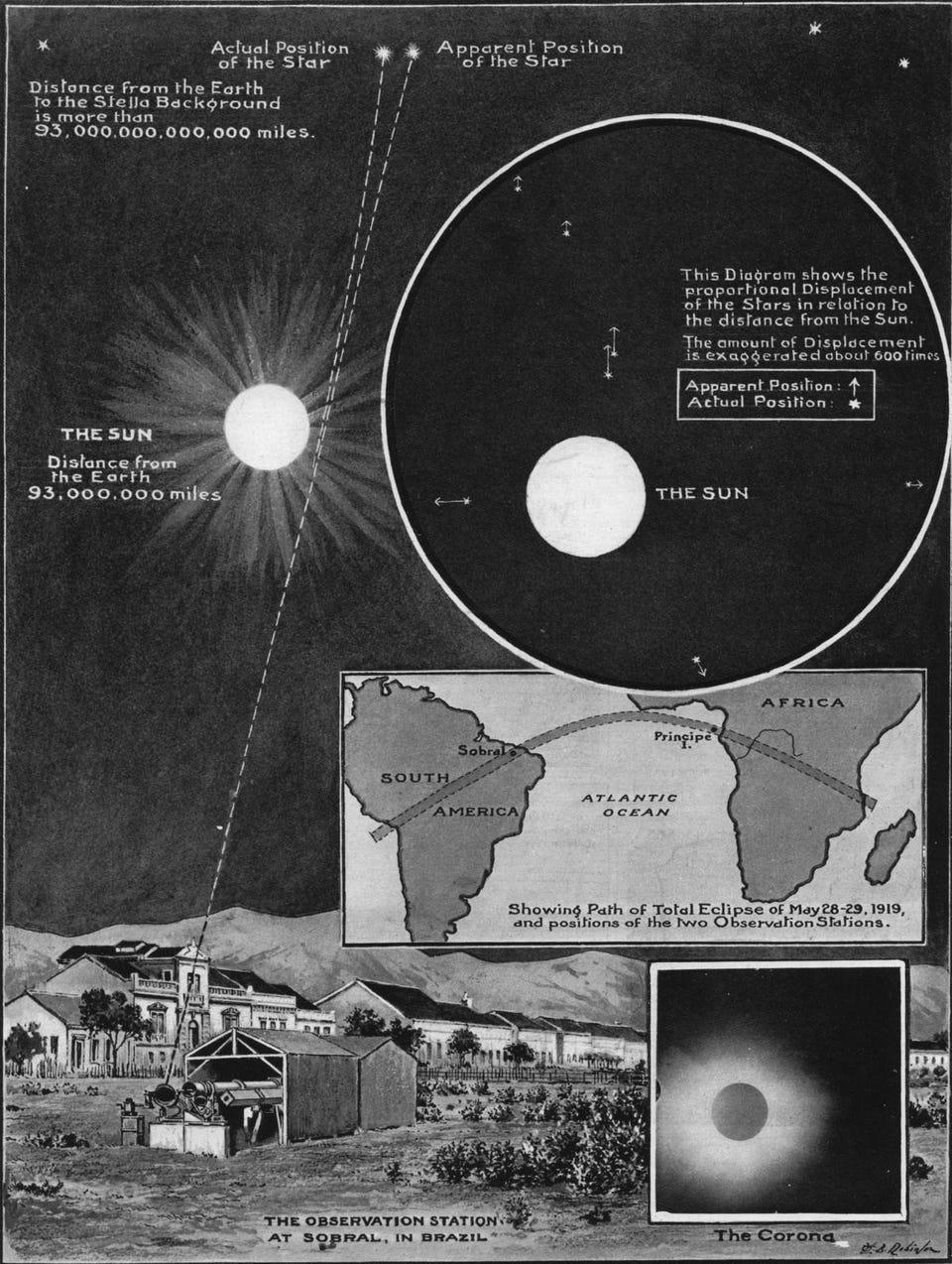

What’s kind of remarkable about this story is that one of the key tests of Einstein’s relativity came in 1919: during a total solar eclipse. According to Einstein’s theory, the presence of a large amount of energy, all in one location in spacetime (the Sun), would bend and distort the path of all objects that traveled close to it. This included the light from background stars, which, although massless, would still follow the path created by curved space: the important key concept of General Relativity.

But what would the older theory that General Relativity was trying to supersede — Newton’s theory of universal gravitation — predict?

Some people insisted that it would predict zero deflection, since light had no rest mass and Newton’s theory relied solely on mass for gravitational attraction. But others recognized that photons still carried energy in the form of E = pc, and therefore, if you used the energy that photons had in place of where you would’ve typically used mass (i.e., if you substituted a photon’s E/c² in place of the Newtonian mass, m), you could actually predict a deflection for Newtonian gravity, too. The fact that Einstein’s theory predicted double the Newtonian value, and that was indeed borne out by the observations, was the key test that enabled us to verify and validate Einstein’s theory, leading to a revolution in how we understood the Universe.

When you think of Einstein’s most famous equation, you should still recognize how profound the simple statement, E = mc², actually is. It tells us that every massive particle has an inherent amount of energy inherent to it, even when it’s at rest, and that its energy can never drop below that key value: mc². If you want to create a particle like it, you require at least that much energy; if you must create that particle along with its antiparticle counterpart, you require at least double that energy. And if you destroy or annihilate any massive particle away, all of that rest mass energy, all mc² of it, will become part of the energy that all of the “daughter particles,” or particles produced in the annihilation, carry away.

But you should also recognize that E = mc² is only part of the full story: because particles not only exist at rest, but also move through the Universe. The quantity of motion that they carry with them, momentum, leads to a certain amount of energy-of-motion being associated with that particle as well. For slow-moving, massive particles, you can approximate that energy-of-motion with E = ½mv². For massless particles and ultra-relativistic massive particles, you can approximate that energy of motion with E = pc. But if you want the general case, where rest mass and momentum both are included, you need the full equation for the energy of a particle:

E = √(m²c⁴ + p²c²)

As famous as it is, E = mc² is only half of the full equation that’s needed to describe a particle’s energy. To get the other half, you have to remember that you cannot simply describe the Universe by taking a snapshot of it. It has a kind of beauty — and energy — that moves.