How to see the comet of the century from all over the world

- Whether originating from the asteroid belt, the Kuiper belt, the Oort cloud, or even farther, when icy, volatile-containing bodies pass close to the Sun, they develop tails and spring to life.

- Typically thrown into a general classification known as comets, they only rarely become bright, spectacular, and visible to the naked eye.

- But Comet A3, also known as Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS, has not only achieved that, it’s already become Earth’s most spectacular night sky comet of the 21st century so far. Here’s how to catch it for yourself.

Most of us don’t realize it, but our own Solar System is constantly being bombarded in a cosmic game of pinball: where temporary, interloping objects speed through the paths normally reserved only for the planets and their moons. Objects originating from:

- the asteroid belt,

- the Kuiper belt,

- the Oort cloud,

- or even beyond our Solar System entirely,

are all subject to the laws of gravity, and that means when a larger, more massive object passes nearby, it’s capable of significantly changing the trajectory of a smaller, less massive object. Interactions with Jupiter, Neptune, or even more distant bodies can frequently hurl these ~kilometer-sized mixes of ice and rock into the inner Solar System, where the Sun begins to heat them up.

In the most spectacular of instances, these ice-and-rock bodies will be rich in volatile, easily boiled-off material, causing them to develop spectacular dust and ion tails, which we usually identify as comets. With the widespread loss of dark skies due to artificial lighting and the rise of LEDs, very few of us have seen a naked-eye comet since Hale-Bopp prominently graced Earth’s skies in 1997. The 21st century hasn’t yet had a spectacular great comet, but with Comet A3, also known as Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS, about to swing behind the Sun from Earth’s perspective, there’s a chance it will become the best visual show of the 21st century so far. Here’s how to catch it.

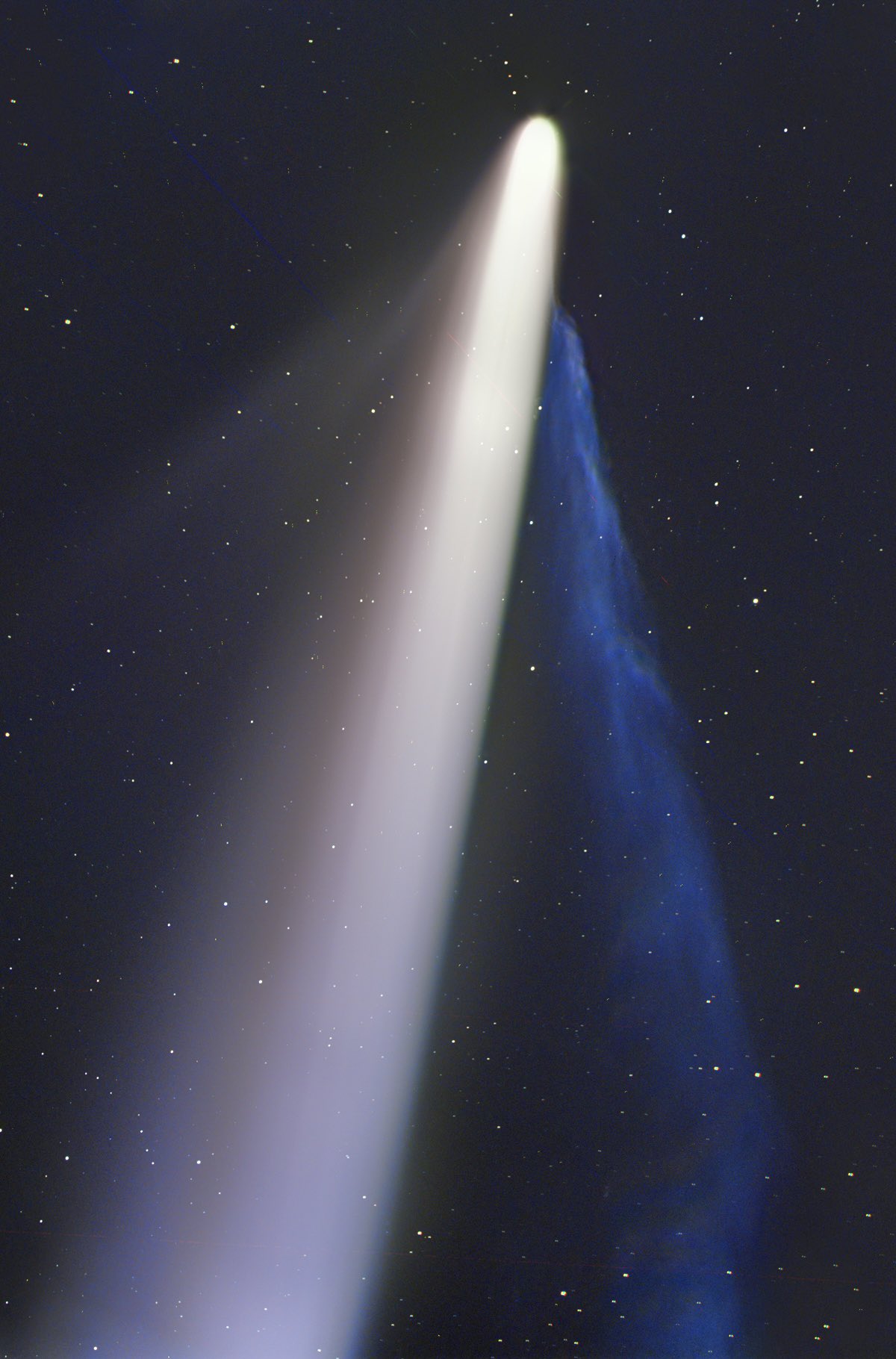

When these volatile rich bodies begin approaching the Sun, the combination of solar radiation — i.e., all forms of sunlight, including ultraviolet, visible light, and infrared radiation — along with solar wind particles all strike the outer surfaces of these ice-rich bodies, and when they do, they have a dizzying array of effects. We normally think of objects in direct sunlight as likely to heat up, but for an object like an incoming comet, it’s really only their surfaces that get bombarded with these energetic phenomena; their insides, only slightly beneath the outer surface, remain at freezingly cold temperatures. As a result, the comet’s insides remain frozen solid, but their outer surfaces begin to sublimate and boil off, leading to a spectacular set of features.

Molecules and atoms can become ionized, where their electrons get stripped away. Bonds can be broken, and compounds such as water-ice, carbon monoxide, nitrogen, and carbon dioxide can all sublimate in the sunlight, creating a glowing “coma,” or a spheroidal halo, around the comet. This helps create cracks and fissures in the comet’s surface, from which particles often escape. The escaping particles that remain bound together in large chunks become dust grains, which contribute to the comet’s main, curved tail. The tiny ions are accelerated in the same direction as the solar wind, which is why they always point directly away from the Sun. While features like a coma can appear when the comet is still as far away as the orbit of Saturn, tails generally grow largest near perihelion: at closest approach to the Sun.

For Comet A3, also known as Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS, it very, very recently achieved perihelion: on September 27, 2024. It came within 58 million kilometers (36 million miles) of the Sun, or about the average distance that the planet Mercury is from the Sun. It was on that night that the comet first became visible to the naked eye: largely for observers in Earth’s southern hemisphere during the pre-dawn hours. Its tail is tremendously long: stretching for several degrees across the night sky; if that’s where you are, you can see still see it throughout the first few nights of October (or, at least its tail, even if the comet’s nucleus itself is too close to the Sun), where it will be about as long in extent as your outstretched fist is at arm’s length.

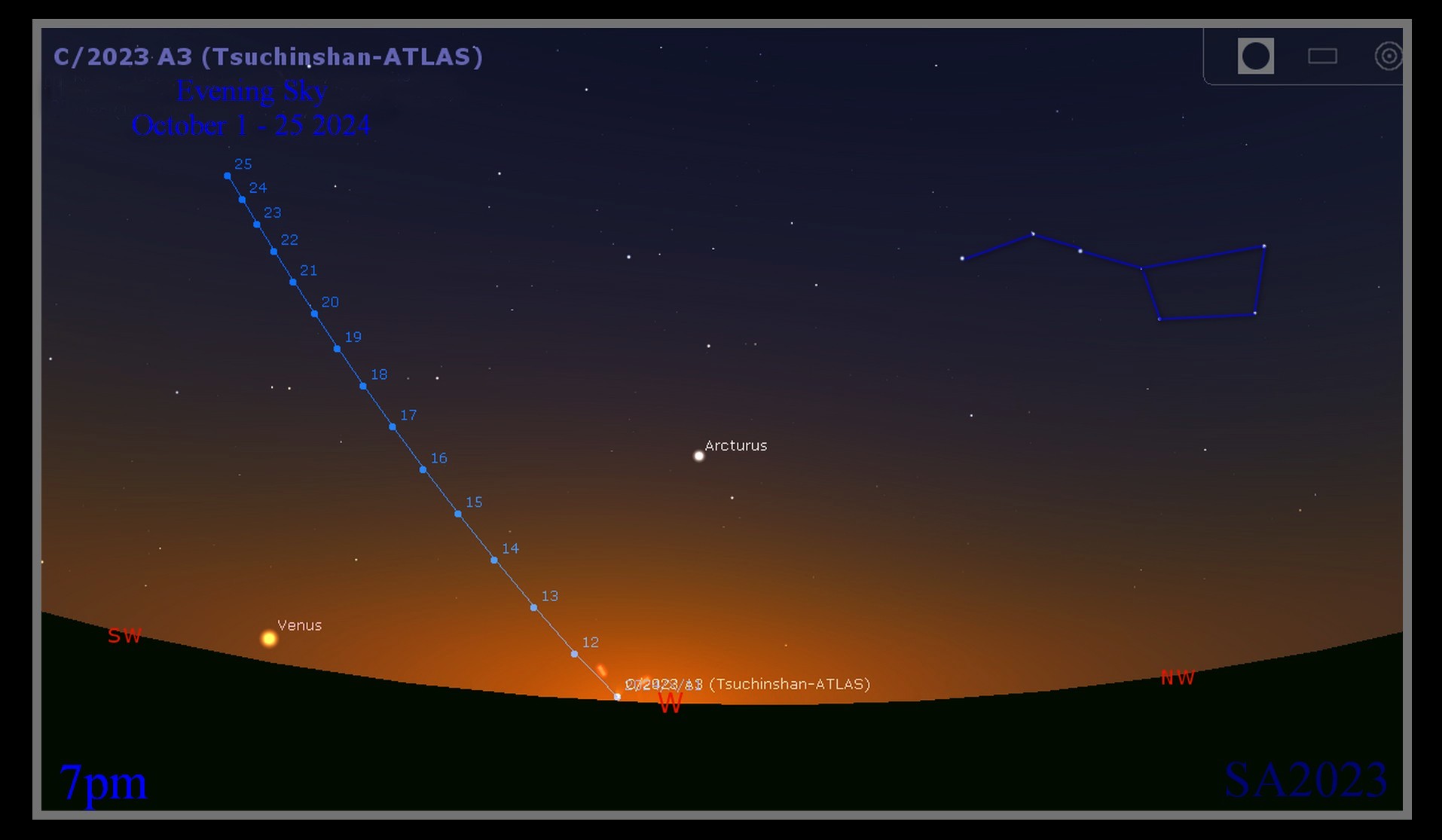

Even though it’s presently some 109 million km (68 million miles) from Earth, the massive size of the tail, driven by its close proximity to the Sun, gives it such a large angular size as well as its present, extreme brightness. On the morning of either October 3rd or 4th, southern hemisphere observers should get their final glimpses of this comet in the pre-dawn skies, as it should then be lost in the Sun’s glare. Over the next week or so, it will depart the Sun, but get closer to the Earth, as both the comet and our own planet continue to move relative to the Sun. It makes its closest approach to Earth on October 12th, where it’s expected to finally become visible to post-sunset skywatchers in the northern hemisphere.

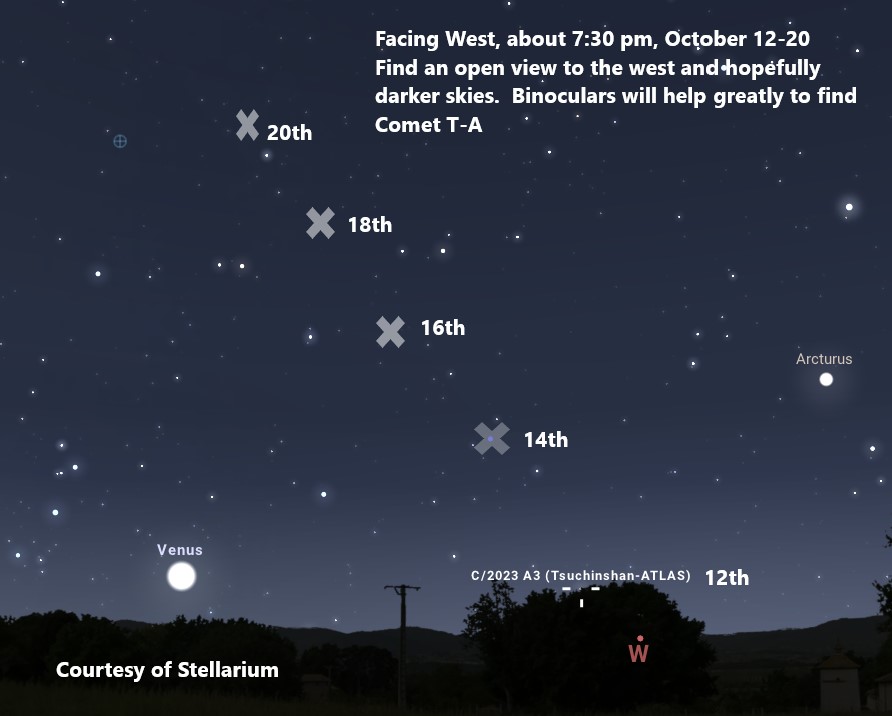

If, like most of Earth’s population, the northern hemisphere is where you live, you’ll be happy to learn that there are clues to help you find it all throughout the sky.

First off, the planet Venus — the single brightest night sky object aside from the Moon — appears low in the post-sunset skies and is usually the first point of light to appear after the Sun goes down: which is why it often carries the name of the “evening star.” If you look in between the imaginary line connecting Venus to the Sun, and then “up” away from the western horizon, you’ll be looking at the prime real estate of the sky where Comet A3 (Tsuchinshan-ATLAS) is going to appear to your eyes.

A little later, even after Venus sets for the evening, there’s a trio of northern hemisphere objects that are easy to identify that will also lead you to the comet. First, start off by finding the Big Dipper, one of the largest and most popular asterisms in the entire night sky. With both a “cup” and a “handle” that its seven (eight, if you include Mizar and Alcor as a pair) stars form the shape of, you can follow the “arc” of the handle to the brilliant orange giant star Arcturus: the fourth brightest star overall and the brightest star in the northern celestial hemisphere.

Continue onward (or, as astronomers say, “speed on”) from Arcturus, and you’ll find the bright blue star Spica, the brightest star in the constellation of Virgo. On your way, when you’re nearly at Spica itself, you’ll run directly into Comet A3; it’ll be unmissable. If Spica has already set, no problem: just draw an imaginary line from Arcturus to Venus, and you’ll find the comet “splitting the difference” between those two bright sources.

On the night of October 12th, Comet A3 (Tsuchinshan-ATLAS) will make its closest approach to Earth, coming within 70.67 million kilometers (43.9 million miles) of our planet, where it’s expected to remain bright enough that even a waxing gibbous Moon won’t be enough to wash out its tail. Over those next two weeks, October 12 through almost the end of the month, this comet may truly shine as the “comet of the century” so far. Even as it moves away — into and through the constellation of Ophiuchus — it should remain visible throughout the month, either with the naked eye or, if it fades, with binoculars or any type of telescope.

The show that the comet puts on during those two critical weeks, from October 12th through perhaps the 26th or so, will all depend on what the Sun “digs up” from deep within the comet as it departs perihelion; something no one can predict just yet. Although the world will no doubt await the views that Comet A3 (Tsuchinshan-ATLAS) have in store for those who dwell in Earth’s northern hemisphere, the southern hemisphere has already been treated to the most spectacular show in at least years, and depending on who you ask, possibly in decades.

Here are a few of the most spectacular images collected so far, from professional and amateur astronomers and astrophotographers alike.

Of course, the comet won’t be completely invisible to all humans as it passes very close to the Sun.

Although the brightness of Earth’s atmosphere prevents Comet A3 (Tsuchinshan-ATLAS) from being visible during the day, or during the pre-dawn or post-sunset hours where the sky is too heavily brightened by direct sunlight, humans who are above Earth’s atmosphere in low-Earth orbit do not suffer from the same difficulties.

Already, Comet A3 (Tsuchinshan-ATLAS) has put on a show unlike anything else for astronauts aboard the International Space Station, as the problems of light pollution and atmospheric scattering are practically negligible from hundreds of kilometers above the surface of the Earth. As captured on September 29, 2024, from low-Earth orbit by NASA astronaut Matthew Dominick, the long, stunning tail of the comet rises like an arrow over the limb of the Earth, while the green curtain of the Aurora Australis (the southern hemisphere’s counterpart of the Aurora Borealis) illuminates the polar areas. Of course, since the Sun is so close to the comet, even in terms of angular size, this time-lapse video compresses more than a quarter of an ISS orbit into under 30 seconds.

It cannot be overstated how impressive the distance and timescales of this comet’s arrival are. Originating from the Oort cloud, at least one-and-a-half light-years away from our Sun, Comet A3 (Tsuchinshan-ATLAS) has taken at least tens of thousands of years to fall into our Solar System from its position so far away. As it sped past the Sun, it achieved a maximum speed of 67.3 km/s, or a whopping 242,000 kilometers per hour (150,000 miles per hour), and may never return again; it’s right on the border of escaping from the Solar System’s gravity entirely.

Getting to see a naked-eye comet is a rarity here on Earth; it normally only happens about once per decade, and we only have a few weeks, at most, where it’s possible. For those of you in the southern hemisphere (or at equatorial latitudes), check the pre-dawn skies as soon as you can to see if you can spot this spectacular show while it’s still very close to the Sun. For those at more northern latitudes, the post-sunset skies beginning on October 12th will provide your best opportunity to spot it. It may not be as spectacular as the last truly great comet to grace Earth’s skies — Comet Hale-Bopp from 1997 — but more than two decades into the third millennium, it may yet be the new century’s best comet so far!