Colleges should include standardized testing in admissions

- Over the past few years, many colleges and universities have removed the requirement for standardized testing in college admissions, rooted in the ideas that requiring them hurts diversity.

- While both the SAT and ACT are imperfect tests that don't necessarily measure future academic or career success, the data strongly shows that standardized testing scores improve, rather than hurt, diversity.

- If the goal is to increase opportunity for high-achieving students, particularly students from lower-income and rural schools, standardized testing is a vital tool in an administration's admissions arsenal.

One of the most stressful times in a young person’s life occurs when they’re still a teenager: when they make their decisions surrounding applying to college. Should they apply, and is college right for them? Where should they apply, and what steps should they take and avoid taking in the application process? In recent years, that second question has also included the notion of whether or not those prospective college students should take a standardized test — such as the SAT or ACT — as those tests:

- cost money to take (although there is a fee waiver process for those eligible), including each time they take it for students who want multiple attempts,

- cost money to send to the schools the student is potentially interested in,

- don’t necessarily measure a student’s learning, growth, full potential, or their chances for future success,

- and have been claimed to hurt diversity, as standardized tests are a part of the system that can be gamed quite successfully by those with large amounts of resources to invest in succeeding at that test.

However, the goal of the college admissions process is for admissions officers to make distinctions between applicants who are likely to meet with academic success in college (and beyond) and those who are likely to struggle in college. Although it is true that standardized test scores alone tend to favor wealthy applicants, those tests remain a unique and powerful way for colleges and universities to identify students from schools without deep resources that nevertheless have the potential for extraordinary academic success. Here’s why colleges should — responsibly — include standardized testing as part of their admissions process.

The basics: what is a standardized test?

On the surface, the idea of a standardized test is simple, straightforward, and compelling. In an ideal world, you could devise a universally applicable skills assessment test that measures a students current comprehension and problem solving skills in any subject area you like, with mathematical ability (math) and language-and-literature skills (verbal) being the two most prominent subject areas providing the foundation for many future career fields that one can pursue. To that end, the most popular skills assessment tests, the SAT and the ACT, are generally used around the country to attempt to measure precisely that.

However, starting in 2020 — when, notably, the pandemic prevented many scheduled standardized testing sessions from taking place — many colleges around the country switched from requiring the SAT or ACT to making them optional: students could submit them if they liked, but were no longer required to. This decision came around right as these standardized tests were being criticized for highlighting already existing inequities in terms of performance:

- students from higher-income (and predominantly white) schools, on average, score higher on these tests,

- that more time, effort, and resources spent studying for the test improve outcomes on the test,

- and that students from schools with fewer resources, on average, score lower,

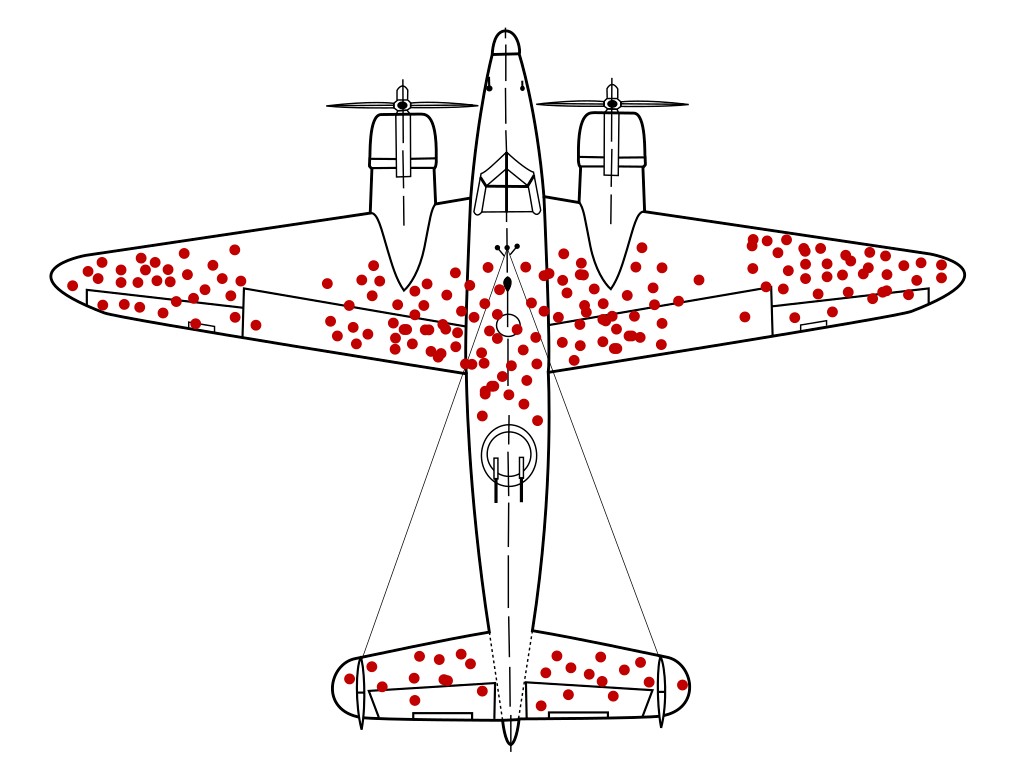

and so it was thought that removing the test requirement would help remove and reduce those inequities. However, as any scientist could tell you, the simple existence of biases built into the data doesn’t mean the data is useless; it means those biases must be accounted for if the data is to be used responsibly.

The dangers of using test score results alone

If the only metric you used in college admissions were these standardized test scores, you’d wind up with an extremely biased population at your college. Higher scores are known to correlate with wealth of the student’s family and with the affluence of the school — whether public, private, charter, and religious or non-religious — as in addition to smaller class sizes and individual teacher attention, that wealth also confers:

- more rigorous and varied course offerings at schools,

- available additional tutoring,

- and dedicated test practice and preparation,

among other advantages. Conversely, lower-income students rarely receive any of these benefits, and so on average they perform far worse on these tests.

Research done in the early 2000s through the mid 2010s clearly pointed this out, showing that the entire test score distribution was shifted, with lower-income students having a lower average SAT/ACT score, and even at the tail ends of the distribution, there were fewer high-scoring low-income students at every score threshold on those tests. Using only test scores as a criteria for college admissions would have created, arguably, a pool of admitted applicants that was even more biased toward high-income students, further disenfranchising those from low-income areas.

The even worse dangers of not using test scores at all

However, it’s been well-established that raw test scores, alone, are not necessarily the best predictive tool for future success, especially for students from low-income backgrounds. Furthermore, it’s in a college or university’s best interest to admit a diverse pool of applicants, as the very idea of a college or university is rooted in the principle that it’s a merit-based system designed to provide opportunity to bright young minds irrespective of their backgrounds. Relying solely on a biased indicator, like standardized test scores, would clearly violate the spirit of providing exactly that type of opportunity to students regardless of their socioeconomic background.

The other criteria used (besides standardized test scores) by college admissions offices typically include:

- high school academic performance,

- letters of recommendation from teachers/mentors,

- personal statements and admissions essays submitted by the student,

- and extracurricular activities,

which typically signify to those working in admissions, as best as possible, a profile of a student’s college readiness. However, many of these “signals of achievement,” including advanced courses such as AP classes, are again similarly tilted in favor of students from high-resource backgrounds. As Yale University recently noted, students of low socioeconomic status “quickly exhaust the available course offerings [at their schools], leaving only two or three rigorous classes in their senior year schedule. With no test scores to supplement these components, applications from students attending these schools may leave admissions officers with scant evidence of their readiness for Yale.”

Since 2020, when many colleges and universities, including the Ivy League schools (generally held up as the paragon of what a college or university should aspire to), moved away from requiring standardized tests, they struggled to identify which students from low-resource backgrounds would meet with the most success in college. Because of the difficulty in comparing one student’s academic performance to another’s across schools, colleges frequently used what’s known colloquially as “affirmative action” to help select which students they should offer admissions to.

However, with the recent, 2023 supreme court decision requiring the complete removal of affirmative action from the college admissions process, students from low-resource schools and of low socioeconomic status had little at their disposal to signal to admissions officers their capacity for high achievement. That decision continued to even further disadvantage students from low-resource schools and students of low socioeconomic status because it simultaneously left intact the most unfair and biased criterion used in college admissions — legacy admissions considerations — enabling mediocre students from the wealthiest backgrounds to receive spots that they did not earn based on merit.

Put bluntly: an inherently unfair system that removes mechanisms by which disadvantaged competitors can shine through their innate talent or ability only becomes more unfair as a result.

Surprising research finds

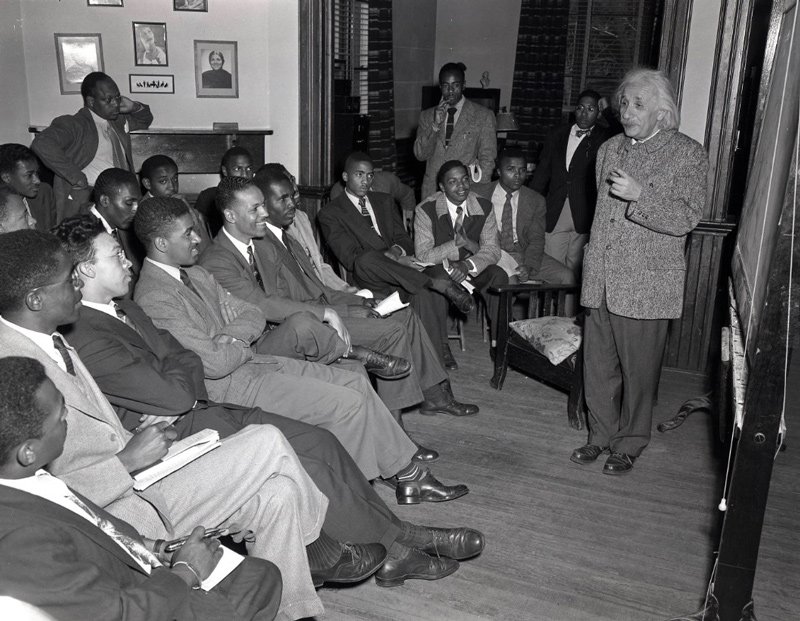

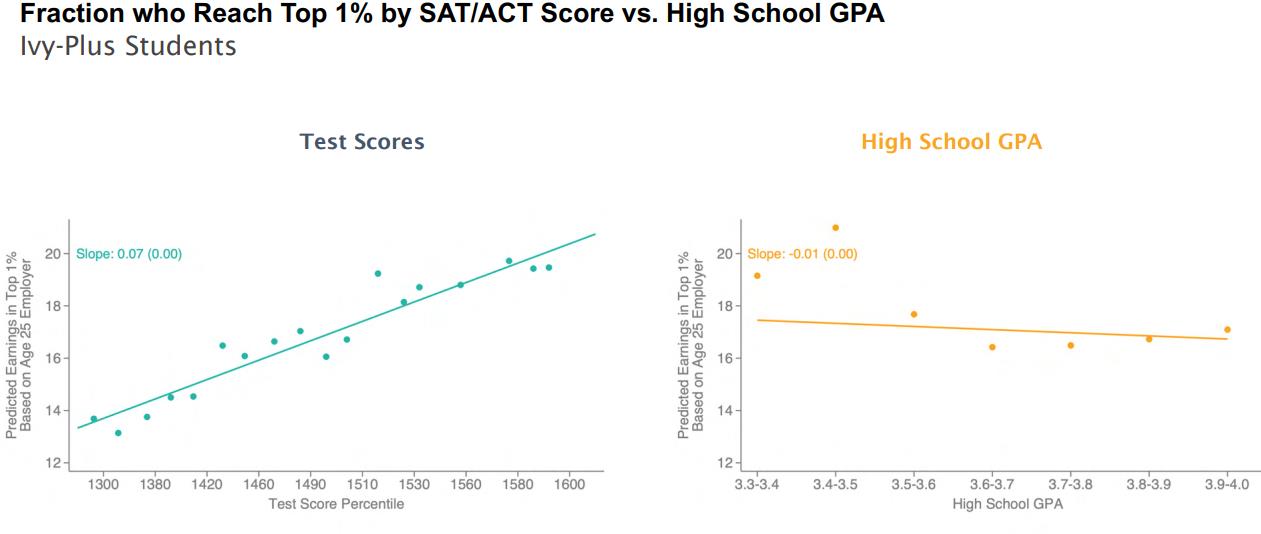

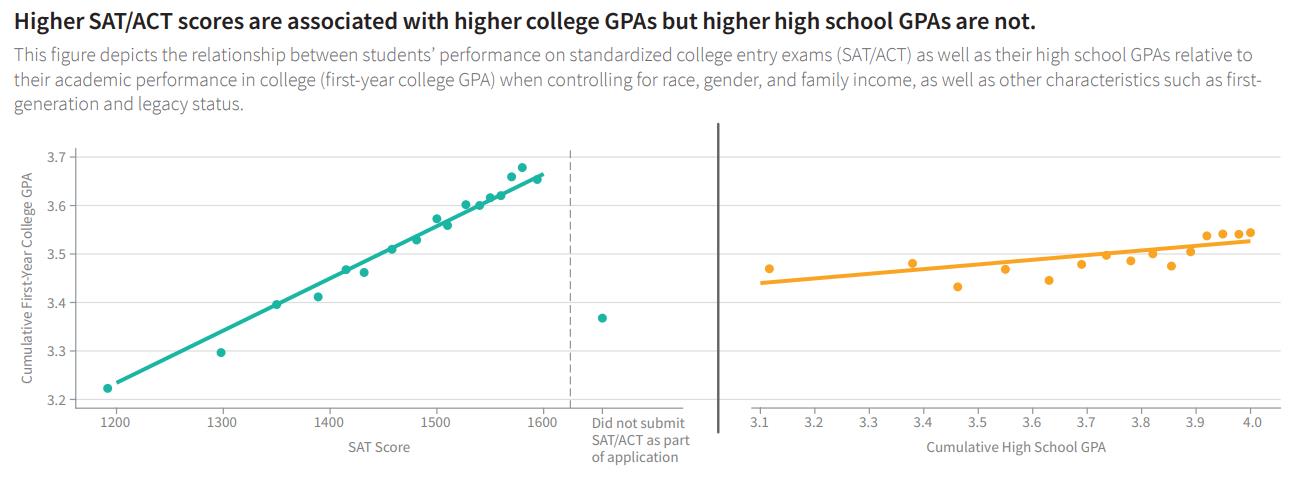

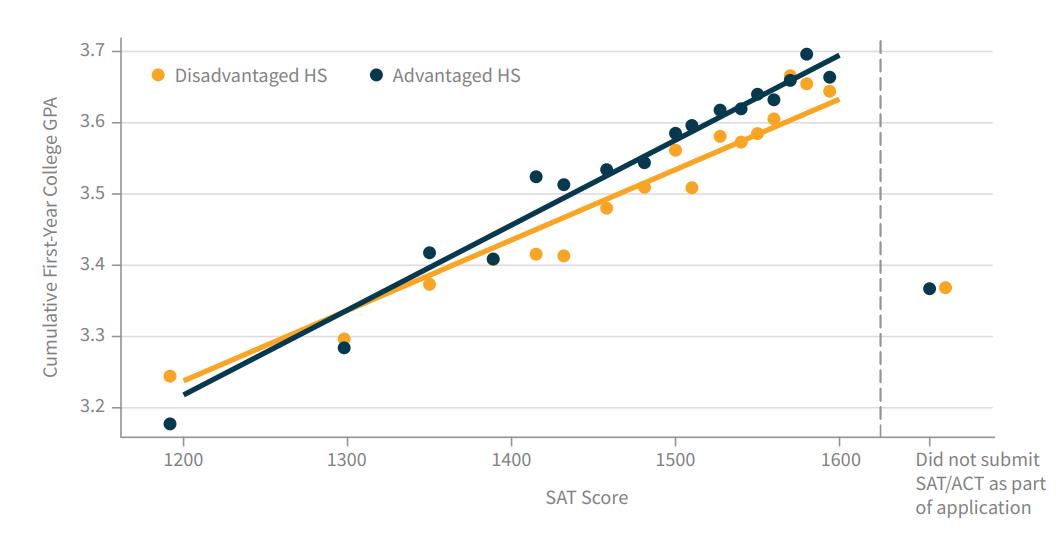

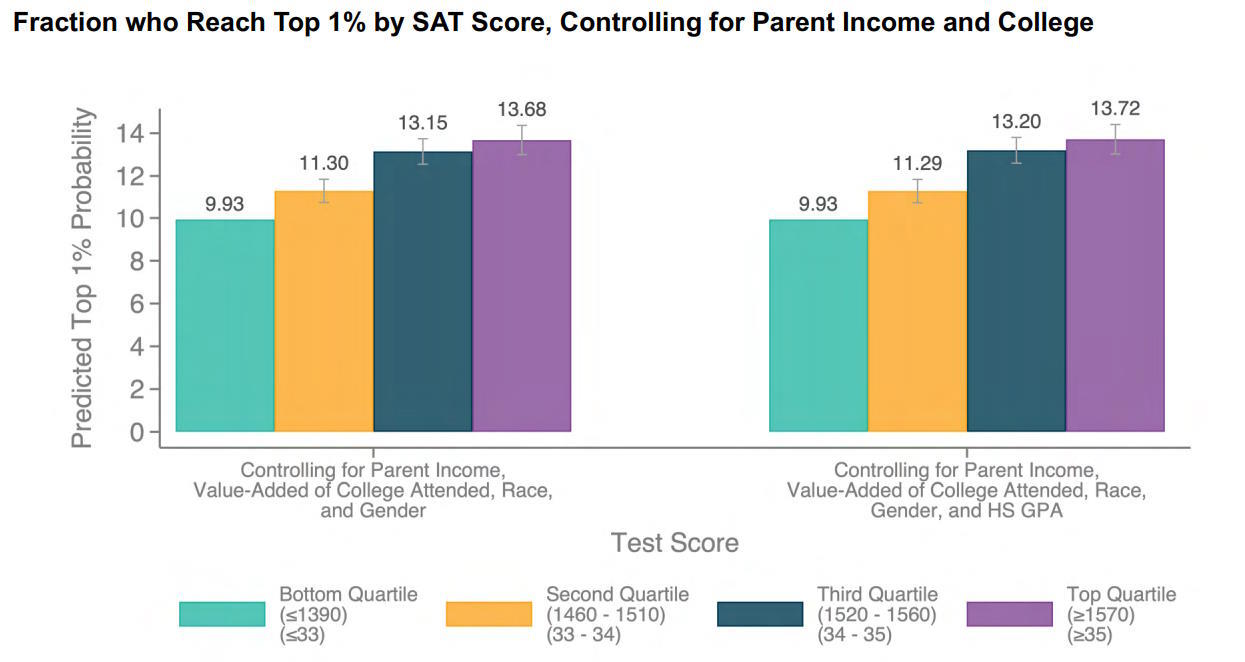

Of course, there are many ideas about how the college admissions process should work, and what criteria would be the most fair and equitable for imposing as far as admitting the best students. Perhaps because of that glut of ideas, the only way to truly identify which solutions are most effective is to take large amounts of data and look at the actual outcomes that have occurred when various metrics are considered. In July of 2023, social scientists Raj Chetty, David Deming, and John Friedman compiled anonymized admissions data from many public and private colleges to study which criteria for admissions were most relevant to selecting students that went on to achieve academic and post-academic success.

Individual schools then began following suit, with first Dartmouth and then Yale becoming the first two Ivy League schools to reinstitute a policy of requiring standardized test scores as part of an admissions package. In fact, what the data showed, both when aggregated across colleges and for individual colleges reporting solely on their own data, is incredibly surprising to many. It turns out that, overall, standardized test scores from students from low-resource schools are actually the single best predictor of future academic success: better than high school grades, letters of recommendation, personal statements, or any other metric. Furthermore, during the “test optional” period of college admissions, the researchers were ably to identify numerous cases where applicants:

- did not submit their scores due to the test-optional policies,

- where had they chosen to submit their score,

those applicants would have, according to Dartmouth economics professor Bruce Sacerdote, “helped that student tremendously, maybe tripling their chance of admissions.”

Using standardized testing responsibly

Certainly, when admissions officers at selective colleges and universities are assembling a profile of a prospective student, they don’t simply base their decisions off of one criterion and one alone. Instead, they assemble as complete a profile as they can, often historically including:

- parent income,

- race,

- gender,

- legacy status,

- status as a recruited athlete,

- High School GPA,

- and, potentially, a standardized test (such as SAT) score.

Assembling a profile in this fashion enables researchers to go back to that data and control for each of those factors, isolating the impact of any one of them in a fashion where the bias induced by the other factors are accounted for.

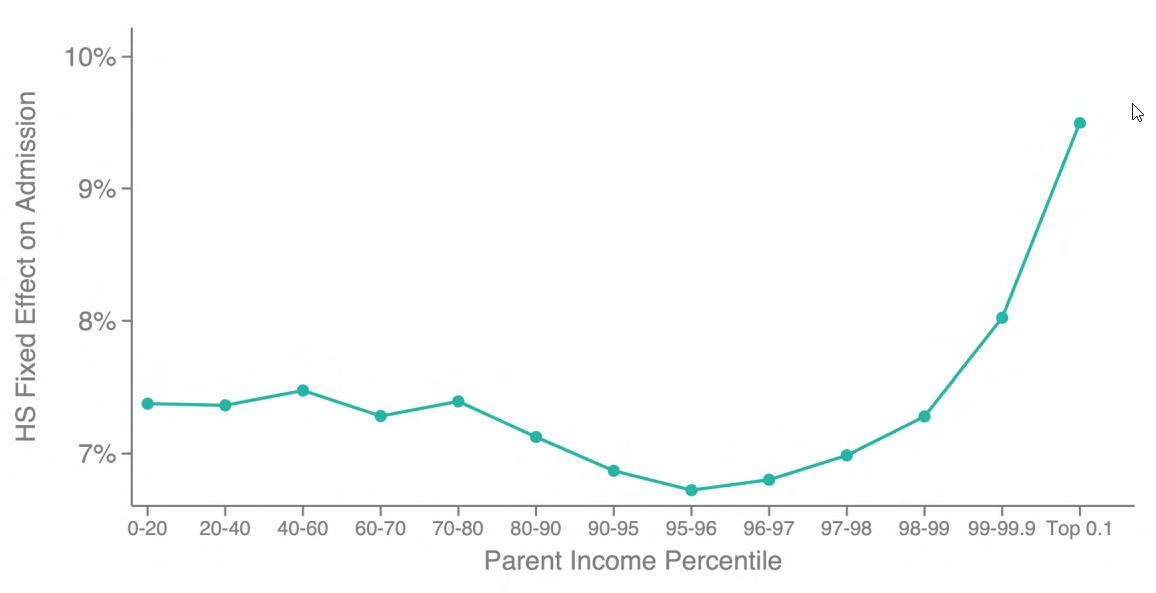

It turns out, when those researchers do precisely that, they find that it is the standardized test score, and only the standardized test score, that allows admissions officers to identify students who stand out among their peers in demonstrating academic potential and college readiness. In practical terms, if you are a student from:

- a household where neither parent attended college,

- a school in an extremely rural area,

- an underfunded school in a low-income area,

- or a low-income household in general,

a standardized test gives you an opportunity to shine in a way that highlights your academic potential, above and beyond any other metric. While performance on a standardized test may only be able to identify a mix of talent, skills, and experience, you can only pay to develop skills and experience. Talent, as much as some may hate to admit it, is not only innate, but is something that standardized tests can often help to identify, particularly when it appears in unexpected places.

To all high achievers: yes, share your scores!

There has been a debate, when one takes a standardized test, over whether you should or should not select the box that allows the testing service to share your score with colleges. The emphatic answer to that question, particularly for students who will likely score relatively high on those tests, is an unequivocal yes, you should. These services, such as the Student Search Service for the SAT and the Educational Opportunity Service for the ACT, can provide a tremendous opportunity for students in under-resourced households, schools, or environments in general.

Sending your scores to colleges means, again in practical terms, that if you score above a certain threshold (that, yes, admissions officers will adjust for your particular circumstances), they may identify you as a strong candidate of interest. If they do, it’s not uncommon for elite colleges, including Ivy League schools, to reach out to you (and other candidates) to strongly encourage you to apply to their school.

Enrolling in the SAT’s Student Search Service (or the ACT’s Educational Opportunity Service) can, in a very real and tangible way, provide opportunities for students to “get noticed” by elite colleges, including by colleges that they never would have otherwise thought could have been an option for them. Prospective students — particularly from rural areas, under-resourced schools, or first-generation households — can be found by colleges (that can often help tremendously with financial aid) in a unique fashion through services such as these.

Who are elite colleges most at-risk of passing over?

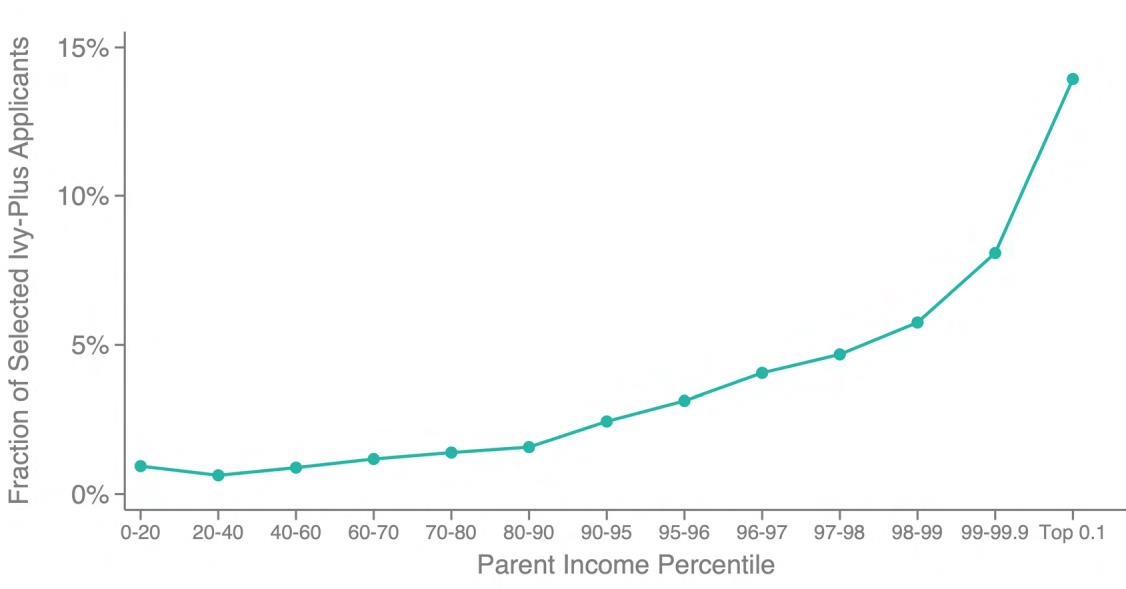

If colleges aren’t kept entirely blind as to the identity and background of a student, including their family’s wealth status, socioeconomic background, and the level of resources available at their High School, we already know who colleges would be most likely to admit. They are most likely to admit students:

- who come from wealthy families,

- who attend resource-rich (well-funded, high-opportunity) schools,

- who have legacy connections to the school itself, and

- who participate in the multi-billion dollar independent educational consultant industry. (That offers tutoring, test preparation, and other ways of “sculpting” kids into templates that will be attractive to Ivy League schools, where consultants frequently charge $120,000+ per year for their services.)

These traits, of course, don’t apply to most students who apply to college. If you, yourself, aren’t from a wealthy background and don’t attend a resource-rich school, however, can you still compete against students who do have all of those advantages? Yes, and moreover, a high standardized test score can identify you as a standout in a way that no other measurement can.

In fact, whether you include or exclude all high school fixed effects (removing variation in student background from the data), the data compiled by various researchers shows the same strong correlation between SAT performance and college success. The high achievers on standardized test scores won’t capture everyone that you want to admit, and all high-achievers don’t go on to achieve that desired in-college as well as post-college success, but neither do all members of any group. When looking at the high performers on standardized tests, they’re definitely among the students a college wants to admit.

Standardized tests as a tool for educational justice

The central idea of the United States, and of a capitalist society in general, is that our society is founded on the principle of equality of opportunity: where the system itself is primarily merit-based, and the highest achievers, based on their own merits, will be the ones who succeed in this world. (Whether this is true, and how true this is, is often debated, but as an ideal, this is a part of our society’s very fabric.) If:

- your parents didn’t go to college (you would be a first-generation student),

- if you don’t have good academic grades and/or extracurriculars,

- and/or if you weren’t fully aware of and prepared for the various criteria that admissions officers look for,

a high standardized test score can be the gateway to an educational opportunity that no other avenue offers. As policy analyst Matt Bruenig put it,

“There is a reason why the scandals surrounding the SAT and ACT generally take the form of rich people paying a ringer to fraudulently take the test for their kid. It’s because dim rich kids can’t outcompete brighter poor kids in that specific arena. There’s real value in that.”

None of this is to say that only students who go to Ivy League (or similar) schools go on to achieve great success in life. Yes, it’s absolutely possible to get a great education and have a great career and a successful life by attending local colleges with open admissions policies that don’t require standardized testing. However, the goal of all colleges and universities is to give students a merit-based opportunity to compete at all levels, including at the very top. For that reason, as well as in the spirit of fairness, it’s important to give everyone, particularly those with fewer resources to compete, an equal opportunity to show what they can do. A standardized test, as the research shows, accomplishes this in a fashion that no other measurement metric can match.