Ask Ethan: How can we know if North Korea is testing nuclear bombs?

Pyongyang says they’ve detonated a hydrogen bomb. Here’s how science can tell us they’re lying.

“In this first testing ground of the atomic bomb I have seen the most terrible and frightening desolation in four years of war. It makes a blitzed Pacific island seem like an Eden. The damage is far greater than photographs can show.” –Wilfred Burchett

Last week, some very, very suspicious seismic activity occurred in the northeast corner of North Korea, just a few miles interior to the coast. Moreover, a statement from the North Korean government claimed that they detonated a Hydrogen Bomb, which they promised to use against any aggressors that threaten their country. This has prompted a lot of concern and fear, but also skepticism from many of you, including Kathleen Reed, who asks:

North Korea claims to have tested an H Bomb, yesterday. CNN was broadcasting images of a mushroom cloud, but now I am unsure if it was from North Korea, or not. How could you and I know if North Korea was testing nuclear bombs, for sure?

First off, your unsureness about CNN’s broadcast footage is spot on. They have a… shall we say… history of saying a lot of things about North Korea and nuclear war and the United States.

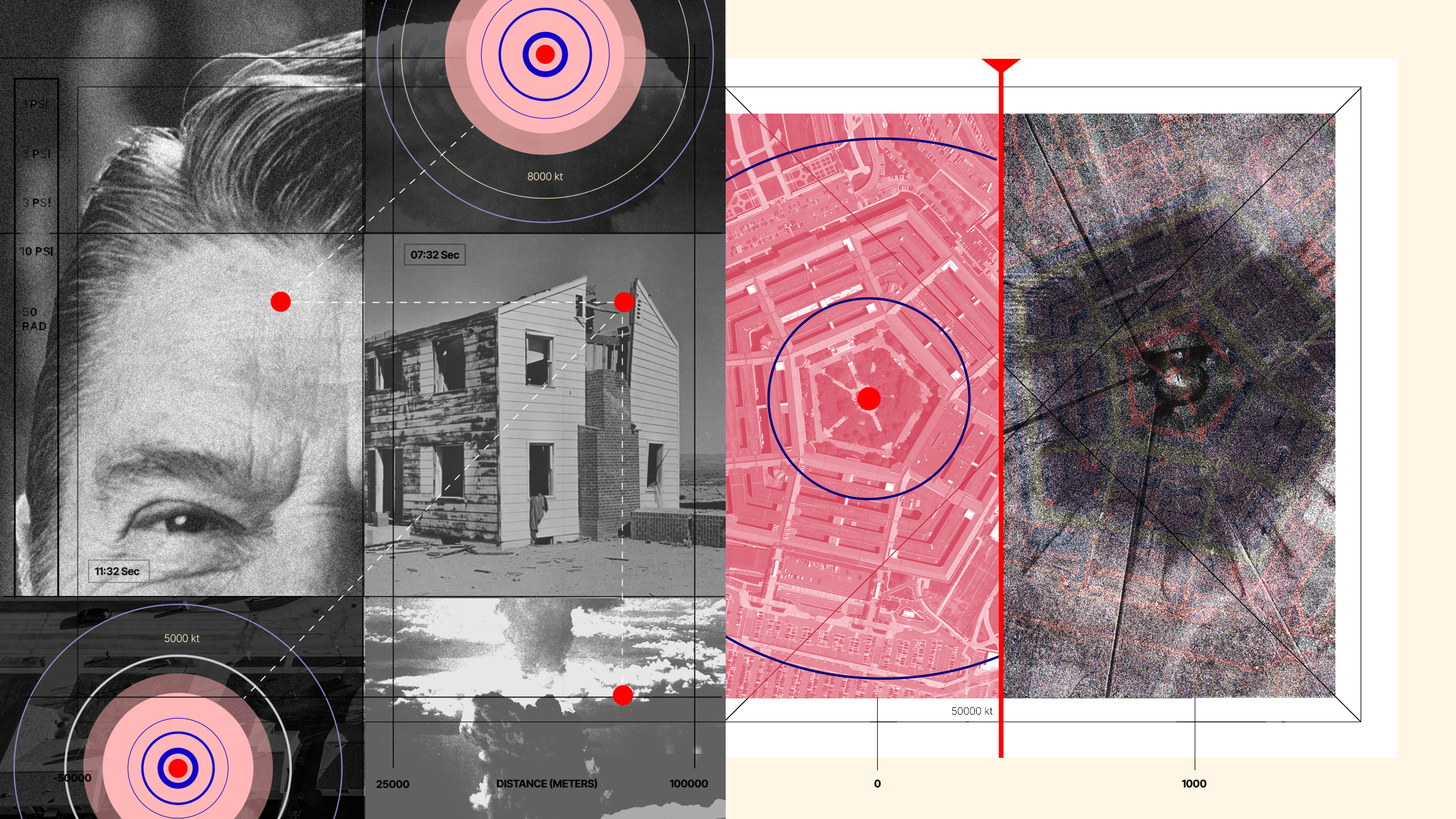

Yes, CNN is claiming this week that North Korea did, in fact, detonate a Hydrogen bomb, and CNN, like multiple news outlets across the world, did show images and footage of a mushroom cloud from a nuclear explosion. The photos and videos of the mushroom cloud are real enough, and what was shown actually did come from a nuclear explosion. But these explosion photos weren’t of a 2016 test over North Korea; they were of various archival nuclear bombs!

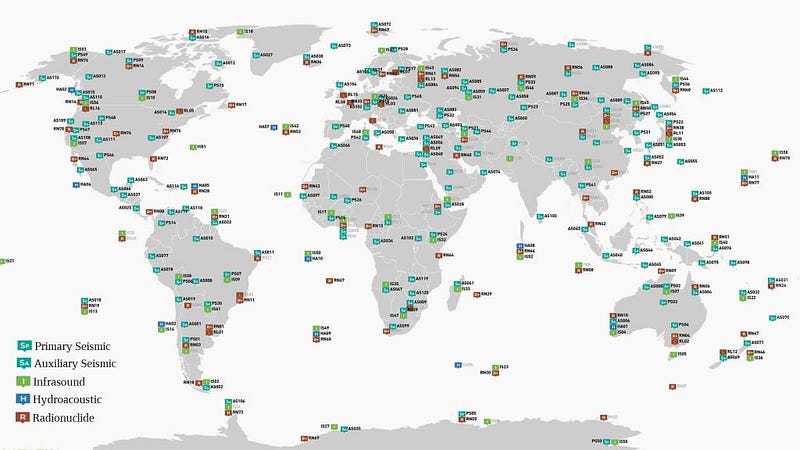

Moreover, you wouldn’t have seen a mushroom cloud from the North Korean nuclear test. Prior to this year, North Korea had conducted three prior nuclear weapons tests, exploding atomic bombs in violation of the 1996 Comprehensive Nuclear Test-Ban Treaty. You can detonate a bomb anywhere you like: in the air, underwater in the ocean or sea, or underground. All three of these are detectable in principle, although the energy of the explosion gets “muffled” by whatever medium it travels through.

- Air, being the least dense, does the worst job of muffling the sound. Thunderstorms, volcanic eruptions, rocket launches and nuclear explosions emit not only the sound waves our ears are sensitive to, but infrasonic (long wavelength, low frequency) waves that — in the case of a nuclear explosion — are so energetic that detectors all over the world would easily know it.

- Water is denser, and so although sound waves travel faster in the medium of water than they do in air, the energy dissipates more substantially over distance. However, if a nuclear bomb is detonated underwater, the energy released is so great that the pressure waves generated can very easily be picked up by the hydroacoustic detectors many nations have deployed. In addition, there is nothing that naturally occurs in the water that could be confused with a nuclear explosion.

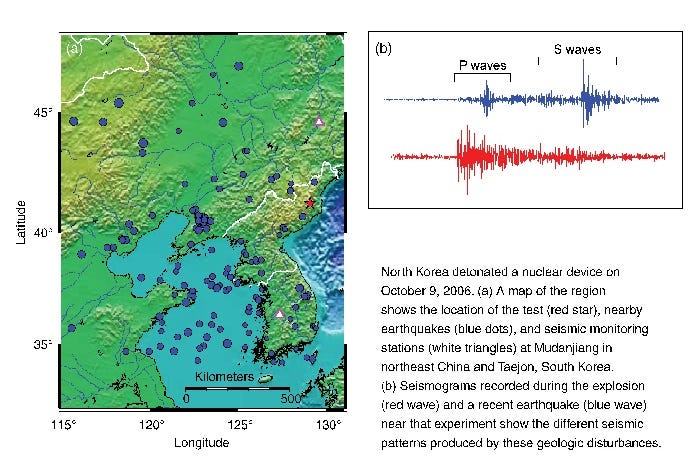

- So if a country wants to try and “hide” a nuclear test, their best bet is to conduct the test underground. While the seismic waves generated can be very strong from a nuclear explosion, nature has an even stronger method of seismic wave generation: earthquakes! The only way to tell them apart is to triangulate the exact location, as earthquakes only very, very rarely occur at a depth of 100 meters or less, while nuclear tests (so far) always have occurred just a small distance underground. To this end, the countries which have verified the Nuclear Test-Ban Treaty have set up seismic stations all over the world to sniff out any nuclear tests that occur.

The North Korean seismic event that occurred was detected all over the world; there are 337 active monitoring stations across Earth that are looking for this. According to the United States Geological Survey (USGS), there was an event that occurred in North Korea on January 6th that was the equivalent of a magnitude 5.1 earthquake, taking place at a depth of 0.0 kilometers. Based on the magnitude of the Earthquake and the seismic waves that were detected, we can both reconstruct the amount of energy that the event released — around the equivalent of 10 kilotons of TNT — and determine whether this is likely a nuclear event or not: and it probably is nuclear in nature.

But unlike previous tests, which were simple fission bombs, North Korea claims this is a hydrogen, or fusion bomb. Fusion bombs are much, much deadlier than fission bombs. Whereas the energy released by a Uranium or Plutonium-based fusion weapon is typically on the order of 2–50 kilotons of TNT, an H-bomb (or Hydrogen bomb) can have energy releases that are a thousand times as great, with the record being held by the Soviet Union’s 1961 test of the Tsar Bomba, with 50 Megatons’ worth of TNT of energy released.

So yes, North Korea probably did detonate an atomic bomb. But was it a fusion bomb or a fission bomb? There’s a big difference between the two:

- A nuclear fission bomb takes a heavy element with lots of protons and neutrons, like certain isotopes of Uranium or Plutonium, and bombards them with neutrons that have a chance to be captured by the nucleus. When capture occurs, it creates a new, unstable isotope that will both dissociate into smaller nuclei, releasing energy, and also additional free neutrons, allowing for a chain reaction to occur. If the setup is done properly, tremendous numbers of atoms can undergo this reaction, turning hundreds of milligrams or even grams worth of matter into pure energy via Einstein’s E = mc^2.

- A nuclear fusion bomb takes light elements, like hydrogen, and under tremendous energies, temperatures and pressures, causes these elements to combine into heavier elements like helium, releasing even more energy than a fission bomb. The temperatures and pressures required are so great that the only way we’ve figured out how to create a fusion bomb is to surround a pellet of fusion fuel with a fission bomb: only that tremendous release of energy can trigger the nuclear fusion reaction we need to release all that energy. This can turn up to a kilogramof matter into pure energy in the fusion stage.

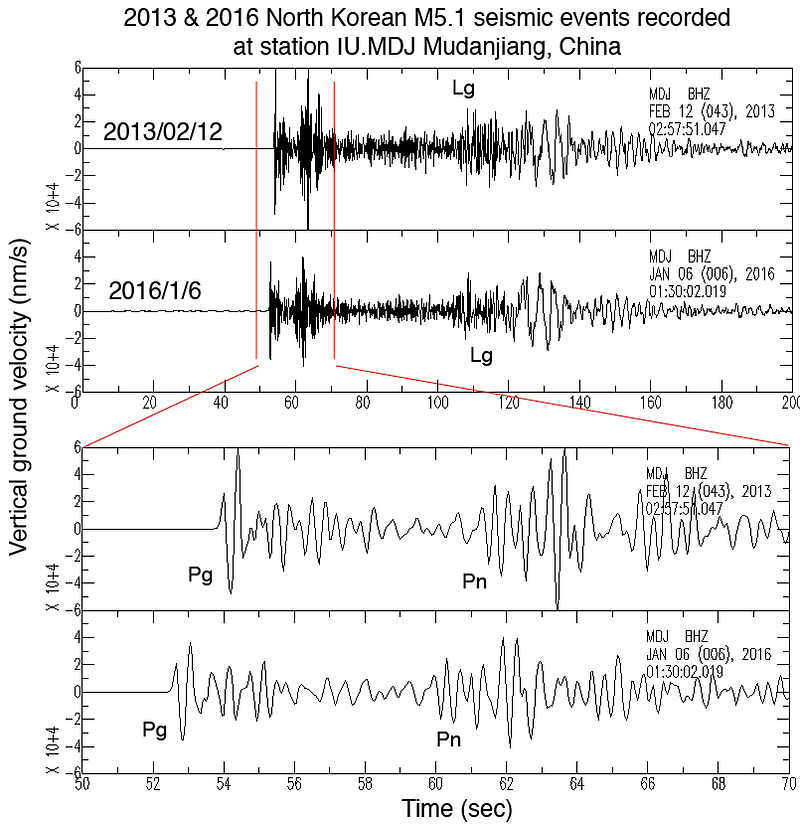

In terms of energy yield, there’s just no way the North Korean quake was caused by a fusion bomb. If it were, it would be by far the lowest energy, most efficient fusion reaction ever created on the planet, and done so in a way that even theorists are uncertain how it could occur. On the other hand, there’s ample evidence that this was nothing more than a fission bomb, as this seismic station result — posted and recorded by seismologist Alexander Hutko — shows the incredible similarity between the 2013 North Korean fission bomb and what we observed earlier this week.

In other words, all the data we have is pointing to one conclusion: the resultof this nuclear test is that we have a fission reaction taking place, with no hint of a fusion reaction. My hunch is that this was intended to be a fusion reaction; perhaps there was a second-or-third stage intended to this bomb that would have resulted in the fusion of hydrogen into helium, but that part of the bomb was a dud.

Regardless, this definitely was not an earthquake! While earthquakes generate very strong S-waves compared to P-waves, nuclear tests generate much stronger P-waves, consistent with what we’ve seen. North Korea did perform a nuclear test, but it was fission, not fusion, and that’s how we know!

Submit your questions and suggestions for the next Ask Ethan here.

Leave your comments on our forum, and check out our first book: Beyond The Galaxy, available now, as well as our reward-rich Patreon campaign!