Ask Ethan: How Can We Help Young Black Physicists Succeed In Their Careers?

Only 3% of physics graduates and 2% of astronomy graduates are Black. That’s got to change.

In the late 1990s, about 5% of the approximately 4000 bachelor’s degrees in physics per year were earned by Black Americans. Since that time, the representation of Black scientists earning bachelor’s degrees has increased in many fields, including earth sciences, computer science, chemistry, and engineering. But even as undergraduate interest in physics has increased — from 4000 to 9000 bachelor’s degrees, nationwide — the representation of Black Americans in that field has dropped. With just ~3% of bachelor’s degrees in physics and ~2% in astronomy awarded to Black Americans, these two fields have the lowest representations of Black Americans of all STEM fields.

While there are many actions that institutions and peers can take to make a difference, there’s also the unmistakable impact that teachers, mentors, and family members can have on individual success. Although I normally identify my question-askers by name and quote them directly, this Ask Ethan column will be different, as I received a letter from a parent of a black physics major. The student, currently taking advanced undergraduate courses and preparing for graduation, has always dreamed of becoming a physicist and working at CERN. Yet, despite that dream, they’ve begun to express doubts about their abilities, competence, and career potential.

What can a caring parent do to support their child at this stage of their life, and what academic and personal advice would best benefit someone in an analogous situation?

Let’s take a look at a series of challenges that such a student will face, and give you the best advice I can muster on every one of them.

Self doubt, or the issue of impostor syndrome. There is this feeling that people — particularly in the sciences — get at many stages of their careers: this feeling that they don’t belong, that they’re not smart enough or knowledgeable enough, that they’re some sort of a fraud, and that it’s only a matter of time before everyone else realizes how little they actually know. It’s common to feel this way; it’s perfectly normal to feel this way; and except in exceptional circumstances, it’s not merited at all.

In order to become good at physics, much like becoming good at piano, swimming, or public speaking, you have to practice. Particularly in the early stages, where we have the most room to learn, we’re going to:

- make mistakes,

- encounter problems that we don’t know how to solve,

- and notice the ways that some, most, or even all of our peers don’t struggle with material that we, ourselves, struggle with.

All of that is perfectly normal, and there are often kernels of truth in our self-doubt. That’s not necessarily a bad thing; noticing where we have room to improve is often a prerequisite to growing, learning, and getting better at things that are important to us.

But what we all too often forget about is how much we actually do know, and what we’ve demonstrated that we’re capable of. We discount our own skills all the time, including the problems we do know how to solve, the research we have successfully conducted, the courses we have demonstrated our competence in, and the skills we now possess based on our experiences.

As undergrads, we’re often told to focus on our GPA or our test scores, when we should be asking ourselves about what we’re capable of accomplishing when given the opportunity. The only thing that GPAs and test scores matter for, at the end of your undergraduate education, is getting your foot in the door for the next step. Once you’re there — at your job, in graduate school, at your internship, whatever it is that comes next — all that matters is how you perform where you are right now.

And anything you don’t know when you arrive at that next step, even if it’s expected that you’d already know it, you can always learn once you’re there. We all have gaps and deficiencies in our education, but we can fill them in with time and effort. Don’t overlook the importance of the things you excel at.

Classes are getting more and more difficult. This is something that, at least in physics, often shocks people. The leap in difficulty from an introductory undergraduate course to an advanced undergraduate course is tremendous, and the further leap from the undergraduate course to the graduate course (or, again, from the graduate course to the advanced graduate course) in a particular subject is comparably large. There are enormous expectations on everyone at those more advanced levels to perform at an extremely high level.

The best advice I can give you, that very few people will tell you, are as follows.

- Students who work on problem sets collaboratively, in groups, as well as on their own, outperform students who only work on their problem sets alone.

- Developing good habits — reading the material-to-be-covered before class, taking good notes, and then working through your notes (and the material covered) after class, on your own — can be extraordinarily helpful.

- And once you’re done with classes, even in graduate school, all that matters is how your research goes and what you can do.

In the end, the classes are the hurdles you clear, but it’s the finish line that truly matters. How well you do in your classes is only very slightly related to what kind of particle physicist you’ll wind up becoming.

Taking the next step — applying to graduate schools — is daunting. This is a challenge for every student, but particularly for students without a mentor that they feel connected to. The lack of available mentors that look like you, as well as the lack of cultural peers, has been shown to disproportionately impact underrepresented minorities in the field. For mentorship, you may want to seek the support of groups that center the challenges you’ll be facing: the National Society of Black Physicists is an excellent example for your particular concerns.

There’s also a concern over family support and expectations in general. What many have referred to as “family inertia” can be a barrier for many, as families that have narrow ideas of what counts as a successful path (medicine, law, or finance, for instance) can discourage students from pursuing their own dreams. If you want to support your child, be aware of even inadvertent discouragement that you may be communicating to them; these micro-aggressions can add up.

If you can send the message to your child that they are worthy of using their life to pursue their dreams, and that they are under no obligation to financially support you while they go after them (which can also be a disproportionate burden to Black students), you’ll encourage them even further.

In a field like physics or astronomy, my general recommendation is that students apply to between 6 and 8 graduate programs. This is expensive: around $100 per application, plus any testing fees, plus the cost of visiting if you get accepted. Ask for financial assistance if it will make a difference, either from the institution you’re applying to, your home institution, or a third-party scholarship program. When you’re considering graduate programs, I recommend evaluating them on three criteria:

- The overall academic quality of the department: can you get a quality, well-rounded education here, and does it feel like an environment where you can thrive?

- The availability of a candidate advisor you’re potentially excited about working with? If there isn’t someone at this University you could see yourself working with, it’s not a good fit.

- And can you see yourself living and succeeding in this environment for the duration of your PhD program? 5 to 7 years, the typical duration of a physics PhD, can be miserable if you don’t like where you’re living.

Of the schools you apply to, two or three should be dream schools: schools where if you got in, you’d go, no question. Two or three should be target schools: schools where you’d be happy to go if you were accepted, and that you have a realistic shot at getting into, but it could go either way. And two should be safe schools: schools that you fully expect you’ll be accepted into. When the time comes to make a decision, you may choose a “safe” or “target” school even over a “dream” school; that’s ok. Trust your brain and your gut combined; if you get a bad vibe visiting a place, it’s not for you. (Trust me.)

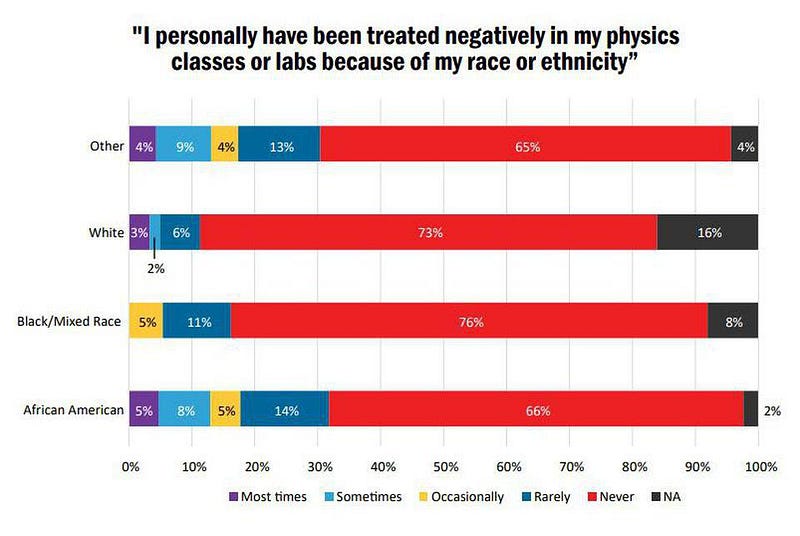

What about the unique challenges one faces as a racial (or other) minority in the field? Although the makeup of many fields are rapidly changing, physics and astronomy are still dominated by a culture of primarily white, heterosexual men. If you’re non-white, non-heterosexual, and/or non-male, you’re going to experience some level of “othering” in your environment. (Odds are, if you’ve made it this far, you’ve experienced some of it already.)

This is a problem with the environment you’re in, but there are insufficient resources devoted to correcting the problems of the toxic elements of that environment. Unfortunately, that means the task of successfully navigating through the toxic aspects of that environment will fall to you and whatever support system you’ve managed to build or acquire on your own. Many people wind up leaving the field because, to put it bluntly, they’re tired of putting up with bigotry — whether targeted or inadvertent, whether due to malice or cluelessness — on a continual basis.

What I think everyone should realize is that only a few people who adopt toxic attitudes can successfully drive underrepresented groups out of the field. If only 3% of physics students are black in a department of 100 students, a single student who makes racist or racially insensitive comments can negatively impact all of the black students. If one person says something egregious — whether interrupting and talking over you, making a targeted joke, or otherwise belittling you — but no one from their own in-group, including a professor, pushes back against them saying it, what happens next?

A few people will laugh, and that laughter will sting. You’ll wonder how many of those who stood by, silently, actually agree with those toxic comments. And you may begin to doubt yourself, to feel alienated from your peers, and you may even think about quitting the field entirely. As the AIP’s TEAM-UP report noted:

“Regular exposure to unsupportive peers and faculty who make discriminatory comments, intentionally or unintentionally, will likely derail a student’s success in the field… and this is more likely for minoritized students in STEM compared with other fields.”

But don’t forget that their comments aren’t about you at all; they’re reflective of their own insecurities. The fear of a competent black person — or a competent woman, or competent gay person, or a competent non-binary person — is really their own fear that they aren’t good enough, and that they need to “punch down” to an already marginalized group to feel better about themselves.

The best thing that I’ve found you can do in such a situation is to find a group of people who make you feel like you have a supportive environment and a sense of belonging there. Fostering a counter-narrative where you receive the message “you belong here” is an incredibly powerful tool in transforming your self-perception from impostor into one of a future scientist.

How do I know whom to trust, and how far should I trust them? This is a tough one, because we’ve all been duped into trusting someone whom we later discovered was unworthy of that trust. The best metric I’ve found in evaluating someone is this: how do they respond when a minority group that they are not a member of experiences an injustice? Are they sympathetic, neutral, or do they blame the oppressed? Are they spurred to act and/or speak out, or are they silent, or do they join in?

If someone will stand up for others, they’re likely to stand up for you. If someone will stand up for others but only if someone else takes the lead, that’s good information to have, but less useful. And if someone won’t stand up for others, or even makes it known that they advocate against the inclusion of others, make sure you note that you’ve found a toxic person that belongs on your whisper-campaign list.

Also, do not be afraid or ashamed to seek mental health counseling. Graduate school is challenging for even the best-prepared students, and toxic behavior is rampant among academics. Cultural and familial baggage can often contribute to discouraging people from seeking available support that would potentially help them through a difficult time; there is no shame in this. This is another aspect where caring parents can truly help influence a student who may need additional support beyond what they’re capable of offering.

For the entirety of American history, about 12–15% of our country’s population has been Black, a fact that’s still true today. Yet only 3% of physics and only 2% of astronomy bachelor’s degrees are awarded to Black Americans. The studies have been done and it is not because of an inherent difference in abilities or interest; it’s primarily because of unsupportive peers and faculty combined with a lack of financial support. The more we can do to remove those barriers and instead send the message that “you belong here” and “your presence here is valued,” the better we can advance, serve, and promote the physical sciences for all of humanity.

Perhaps the best things to focus on are these: if you’ve made it this far, you’ve already proven that you’re capable of becoming a scientist. The best things that can help you reach your goal of becoming a professional physicist are positive interactions with professors, researchers, and peers. Surround yourself, as much as possible, with people who are supportive of you and your goals, and who make you feel like you’re free to be the complete, whole person that you are. This is your life, and you deserve the opportunity to make your dreams come true. All you need is to be given a chance in the right environment, and I hope that’s exactly where you find yourself in the very near future.

Send in your Ask Ethan questions to startswithabang at gmail dot com!

Starts With A Bang is written by Ethan Siegel, Ph.D., author of Beyond The Galaxy, and Treknology: The Science of Star Trek from Tricorders to Warp Drive.