Ask Ethan: Are ‘dark comets’ the Universe’s biggest threat to Earth?

Might Armageddon come not from an asteroid or a comet, but by something completely unseen altogether?

“Honestly, if you’re given the choice between Armageddon or tea, you don’t say ‘what kind of tea?” –Neil Gaiman

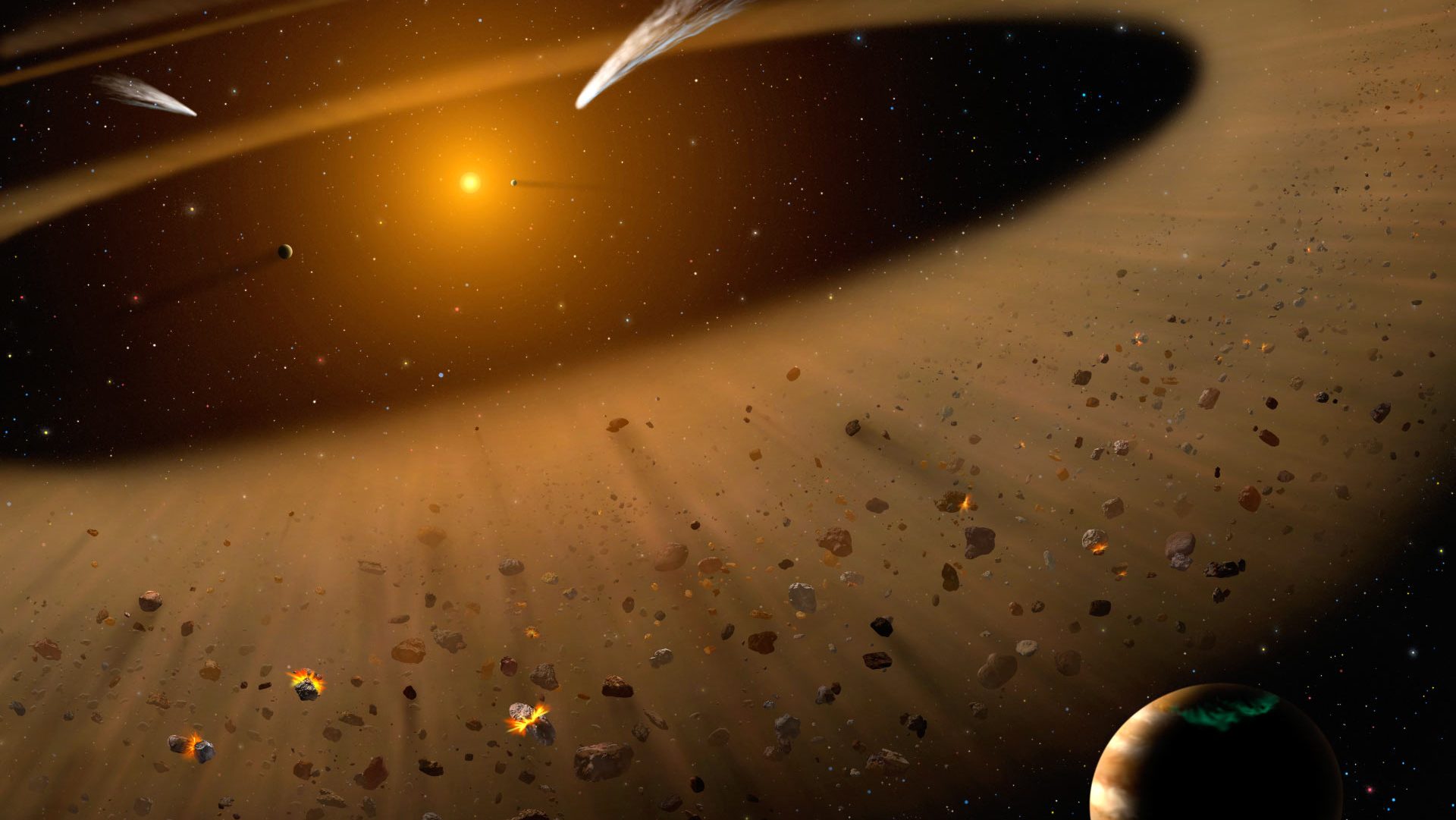

There are many cosmic catastrophes that could do us in, completely irrespective of anything that happens here on Earth. A star could pass into our Solar System and swallow up our planet whole, or eject us from our orbit and cause us to permanently freeze over. A supernova or gamma ray burst could go off too close to us, disintegrating all life on the Earth’s surface. Or, as we know it did at least once before some 65 million years ago, a large, fast-moving object like a comet or asteroid could have a catastrophic collision with Earth. At least if we’re prepared, we ought to see one coming and be able to take preparations. But what if there’s no chance; what if an incoming comet is somehow unseeable? David Bertone heard about that possibility, and wants to know!

I recently came across a few articles regarding dark comets, and to say the least it freaked me out! […] Is Napier right about the dark comets? Are they truly a threat to us [on] earth?

We have lots of threats to life on Earth, and getting struck by a large, fast-moving, unexpected object is certainly among them!

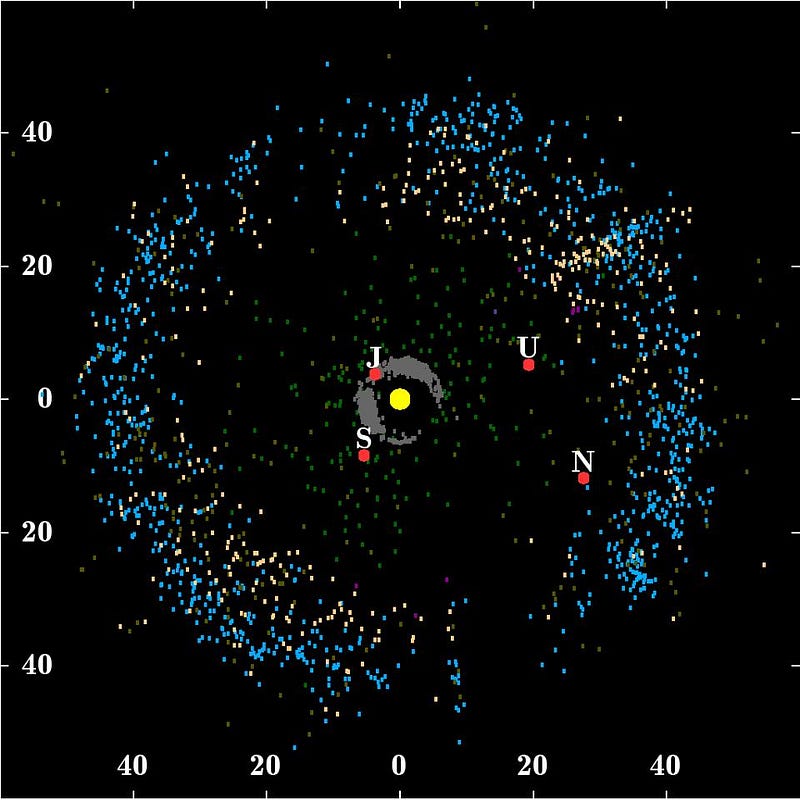

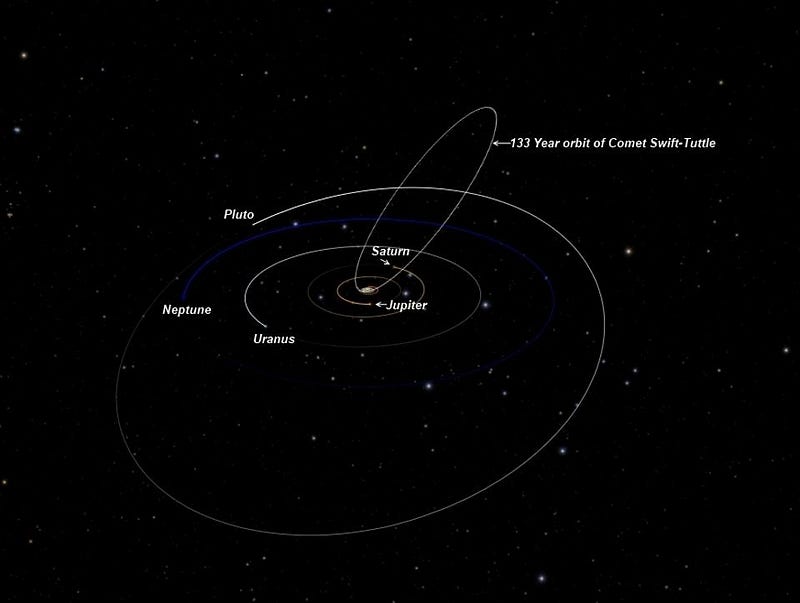

Bill Napier is a scientist who studies potentially hazardous objects from outer space. He rightly points out that, while most efforts to catalogue the potential dangers to Earth focus on near-Earth objects like the asteroids that leave the main belt and cross Earth’s orbit, that might not be a good reflection of what’s actually likely to get us. Nor is it necessarily an asteroid orbiting interior to Jupiter or a comet orbiting exterior to the orbit of Neptune, just waiting to get perturbed and flung into the inner Solar System. There are plenty of objects orbiting in between the orbits of the four gas giants, known as centaurs, that could be hurtled inwards without any warning, and most of them have not been catalogued. Napier postulates that many of these centaurs may be invisible to us, even after being flung inwards, until it’s far too late.

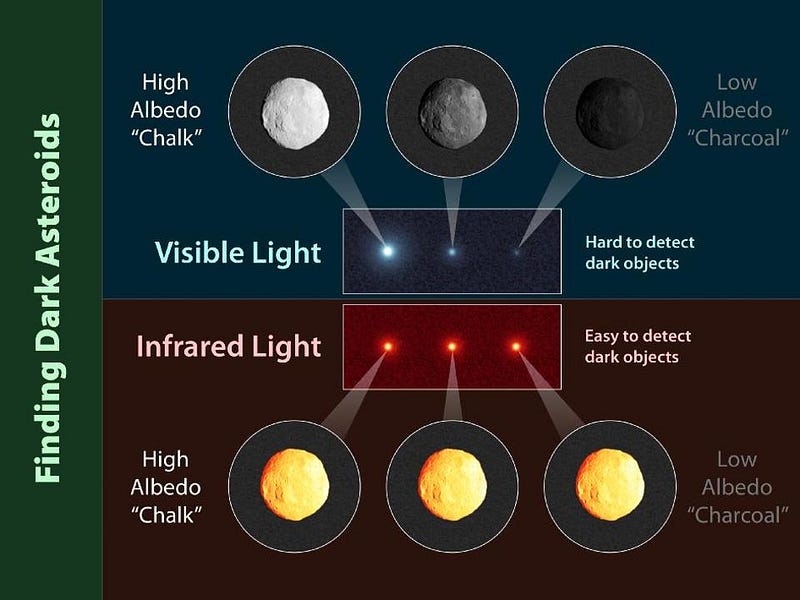

But this brings up an important question: what could render a comet dark, or otherwise unseeable? It isn’t simply going to be a comet that comes towards us from the outer Solar System that’s terrible at reflecting light. Sure, a centaur could have had all its volatile ices boiled off over billions of years, reducing its reflectivity tremendously. As obvious as that seems, the amount of light the Sun emits is so extreme that even a medium-sized comet (or centaur) that absorbed 99.9% of the Sun’s light would still be easily visible at the distance of Saturn. Moreover, comets tend to be made up of mostly ices, which are highly reflective and which get brought to the surface as a comet heats up. The only thoroughly ”dark” bodies in our Solar System are more like our Moon, which still reflects light very brightly, as any casual watcher of the night sky will tell you. An object that was as dark as any naturally occurring, abundant element or compound would still be visible from its reflected sunlight, particularly if you looked in the infrared portion of the spectrum.

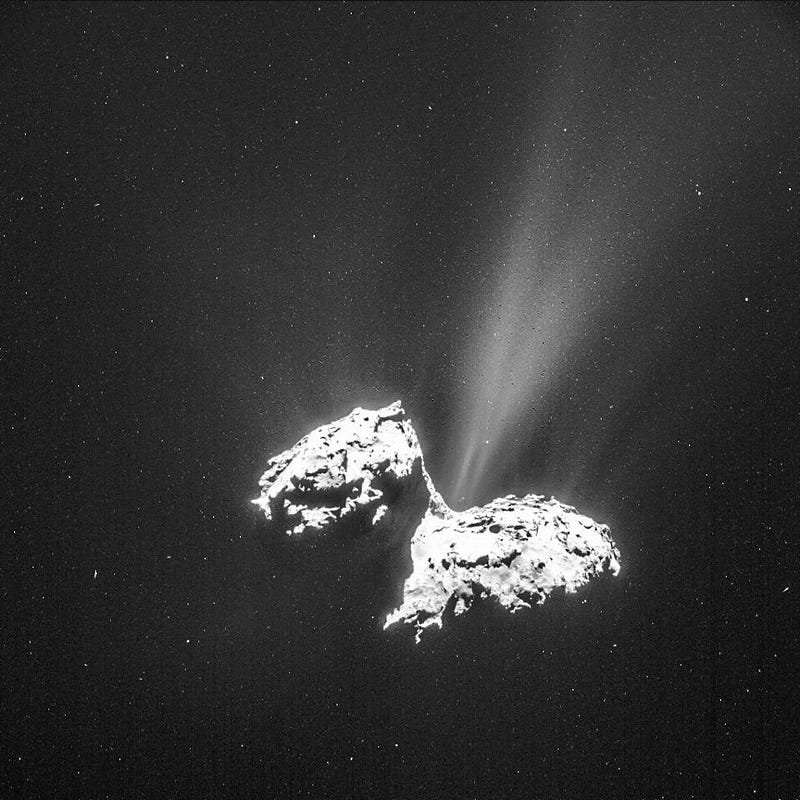

But there are other possibilities to consider. What if an incoming, highly reflective comet were oriented bizarrely? What if it was quite icy, but reflected all the sunlight that struck it away from Earth, like some kind of strange crystal? It’s less obvious, but that wouldn’t work, either. When an object like that entered the planet-containing portion of the Solar System, it would heat up. Heat acting on the ices causes the development of a long tail that points away from the Sun, and this will be easily observable from one of many professional or even amateur all-sky surveys before too much time has passed.

But perhaps nature will conspire to make that tail unseeable from our point of view? In order for the tail to be hidden, the incoming comet would need to be directed straight at us, aligned so that the Sun, the Earth and the comet made a straight line. If the tail points directly away from us and is hidden behind the comet, that would render everything invisible, and we wouldn’t be able to see it, right? Unfortunately, that’s wrong, too. Comet tails don’t simply point away from the Sun, they spread outwards away from a comet. Even a “head-on” comet like this would have a visible coma around it. Again, amateur or professional astronomers would catch this quickly.

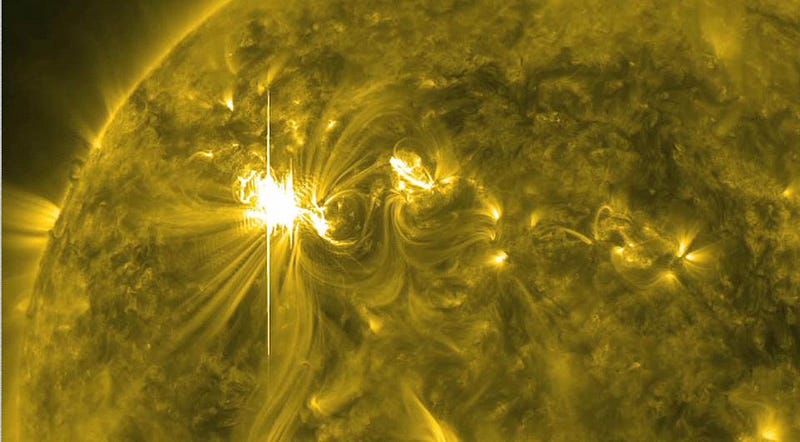

But there is a real danger of an invisible comet, and it’s very different from the form that Napier envisions in any of his scenario. Imagine, if you will, that a bright, reflective, tail-and-coma-containing comet were headed right for us. Is there any direction it could approach us that you can think of that would render it completely unable to be seen? There is: from the direction of the Sun.

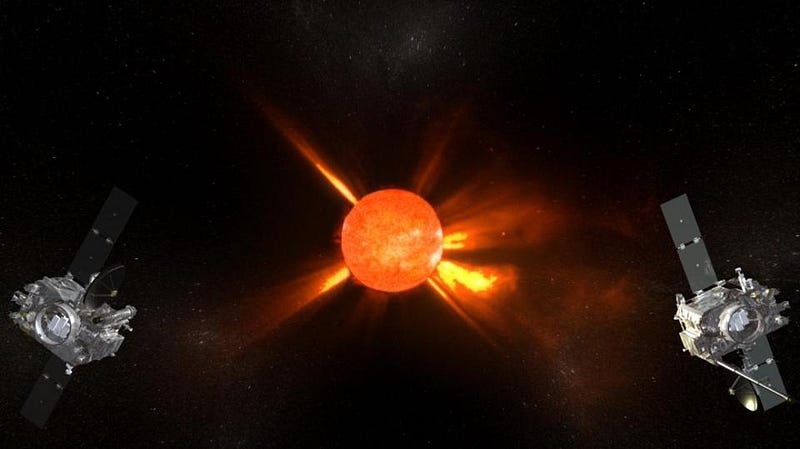

Telescopes don’t dare point too close to the Sun, even from space, since even a glimmer of direct sunlight will ruin and fry your optical system. If any object — comet, asteroid, centaur, even a kicked-up fragment from a collision with Mercury — either approached the Sun from behind it (from our perspective) or were sling-shotted around it, the right trajectory could send it hurtling towards Earth. This is part of the reason why having NASA’s STEREO satellites online is so important.

At this point, the technology to deflect an incoming asteroid or comet a significant amount in a short amount of time hasn’t been developed, but at least by having a set of observatories at different locations in the Solar System, we could see everything that was headed for us. In the future, more sensitive infrared all-sky surveys will make a far more complete census of the centaurs in our Solar System, and the launch of WFIRST in the 2020s will help us map potentially hazardous objects to much greater distances than we’ve presently done. But the odds of a distant object being hurled into us after being perturbed for the first time are exceedingly small; the much scarier prospect is of a long-period comet being kicked ever-so-slightly into Earth’s orbital path.

Comet Swift-Tuttle, which gave rise to the Perseids, is the single most dangerous object known to humanity, and has a chance to impact us with more than 20 times the energy of the legendary dinosaur-killer in the 4400s. But we’ve got plenty of time until that might happen. In the meanwhile, take heart in the fact that except for Sun-directed asteroids and comets, we can see everything large that could come headed our way. And if we’re lucky enough to make it as a civilization for another thousand years or so, our technology will likely have advanced to the point where perhaps asteroid/comet deflection isn’t such a daunting task after all!

Perhaps if it is, there’s always plan B: to clone Bruce Willis…

Submit your Ask Ethan questions to startswithabang at gmail dot com!

This post first appeared at Forbes, and is brought to you ad-free by our Patreon supporters. Comment on our forum, & buy our first book: Beyond The Galaxy!