4 pervasive myths that cause us to abandon science

- There are many legitimate reasons to be mistrustful of some of our most vaunted institutes and ideas, particularly when corruption and bad behavior is easy to spot.

- Yet the past few years have seen the erosion of the public trust in science, even when it comes to irrefutable and robust findings that no serious scientists dispute.

- Here are the four most prominent myths that “merchants of doubt” use to sow distrust among us, and how to see through the ruse and determine what’s actually true for ourselves.

When you think about what science actually is, how do you conceive of it? Do you do what most people do, and default to what you learned in our classes in school, with a layer of cynicism and skepticism layered atop it? That’s understandable, as many of us remember being taught “facts” in our science classes that later were shown to be not as they seemed at the time. It’s as though, somewhere along the lines, many of us were taught isolated facts about the world, and our ability to regurgitate those facts was used as a metric to measure how good we were at science. Many of those facts may have felt absurd; many of the experiments we performed didn’t give the results we were told they should give; many of our experiences didn’t line up with what was written in our textbooks.

If that’s what our experience with science is, then why should we be expected to believe that whatever science “tells us” is actually true?

It’s an understandable way to feel, but it’s rooted in a deep misconception. Only if you possess a narrow, incomplete understanding of what science is and how science works could you wind up in such a predicament. The way out, perhaps, is to slay the four most common myths that agenda-driven advocates leverage to sow doubt about bona fide scientific knowledge. While there are many ways that the world can fool us into believing something that isn’t true, most of the attacks against scientific findings are, in fact, only successful because they prey on how humans often wind up fooling ourselves.

Science, in actuality, is both a process and the full body of knowledge that we have, and it adds up to the best, most truthful understanding we have of the world at any given time. Here are four common lines of thought that we often make to argue against scientific findings, and why each of them is fundamentally flawed.

1.) Science is biased by who funds it. There’s a common narrative that scientists in a particular field are heavily influenced by who funds them, and therefore their results and conclusions are unreliable: driven by the ideology of the funders. Because there are numerous instances throughout history where various industries have published junk science that does indeed promote their agenda — for example, the tobacco industry has famously been caught manipulating research — many people believe that this translates into all science being untrustworthy, particularly wherever it’s funded by some entity they view as ethically questionable.

This has been (mis-)applied to many different realms of science, claiming that because there is a moneyed interest that has behaved unethically at any point in history, therefore the scientists that they fund must be “cooking the books” to obtain whatever results are desired.

- Agricultural scientists must be in the pocket of Monsanto.

- Bee researchers must be in the pocket of Bayer.

- Climate scientists must be in the pocket of big government.

- Clinical researchers who test vaccines must be in the pocket of the pharmaceutical industry.

And so on, across any scientific field you dare imagine.

Of course, these claims are completely baseless. Research only gets to be conducted when there’s funding of some type for that research, and the types of research that receive funding frequently depend on whether someone is motivated enough to be willing to pay for it. However, this doesn’t mean there’s built-in bias toward obtaining a particular result. In fact, it’s clearly in everyone’s interests if the research is conducted ethically and scrupulously. Some reasons include:

- Other scientists will review the results, and if anything is amiss, the fraudulent activity is likely to be discovered.

- If fraudulent research is conducted, the company behind it will be legally liable, which unequivocally harms their bottom line.

- And if the research reaches incorrect conclusions, the evidence for the actual truth will continue to build until a better study is conducted, at which point the correct conclusions will then be reached.

To be sure, there really is fraudulent research that gets conducted all the time; it’s one of the main reasons papers either get retracted or wind up being published in unscrupulous, sham journals. This happens frequently among:

- climate contrarians,

- the “vaccines cause autism” crowd,

- anti-fluoride advocates,

- traditional Chinese medicine practitioners,

- and crackpots of all varieties.

However, you can’t simply cry out “Fraud!” because you don’t like the conclusions. Unless you have strong evidence that fraud was at play, you’re falling for one of the most unethical gambits in all of science (mis-)communication.

2.) Science is driven by public opinion. This is a hard one, because this perception has been on the rise in our society for all of the 21st century. Whenever science begins reaching conclusions that are, shall we say, inconvenient for some people or certain industries, those who would prefer a different outcome take a different tactic than engaging in honest scientific research. Instead, they take a series of scientifically baseless but emotionally appealing claims directly to the expertise-lacking general public. If you fundamentally lack the training necessary to evaluate a scientific or health claim, but someone who you trust and ideologically agree with makes what you perceive as a compelling point on one side of the issue, you’re likely to agree with them about that issue, even if it lacks scientific merit.

Supplements, for example, are largely unregulated as an industry, and those who sell them are legally allowed to make many dubious health claims in a decision that dates back to a disinformation campaign that featured Mel Gibson more than 30 years ago. Nevertheless, most supplements remain:

- largely untested,

- widely ineffective,

- and dangerously understudied.

Some supplements that were legally sold have even led to poisoning, landing those who’ve peddled them in prison. Yet, under the guise of “personal freedom,” many companies continue to market and sell supplements that frequently don’t even possess the ingredients they’re purported to contain.

Similarly, many people still feel that the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, is a hoax, despite the overwhelming scientific evidence of its existence and impact on humanity. Many still disbelieve in the germ theory of disease. Others deny the link between HIV and AIDS. Still others believe that anything natural is good, and anything artificial is bad. Even today, headlines are being made as raw milk advocates rush to stock up on what’s likely to be a disease vector for the deadly H5N1 flu. No matter how true something is — the Big Bang, evolution, the roundness of the Earth — there will be people who have dissenting opinions about it.

It’s often been said that, “Science doesn’t care what you believe,” but the truth is that science doesn’t care what any humans believe, in general. The Universe, as best as we can measure it, obeys certain rules and yields certain outcomes when we test it under controlled experimental conditions. The reason scientists so often find themselves surprised is that you cannot know the outcome of a new experiment until you perform it. The results of these experiments and the knowledge that comes along with it is available to anyone who reproduces the experiment. The results are found in nature, and anyone’s opinion on a scientific matter that’s been decided by the evidence is moot.

3.) Science is limited to knowing “just the facts” that are uncovered through scientific investigation. There are a lot of people who make the largely faulty claim that science can give you the facts, but that anything beyond that — conclusions that it reaches, interpretations that arise from those facts, or recommended courses of action — go beyond science. In fact, a common narrative is that scientists who tread into these waters are overstepping their bounds, and engaging in advocacy, not science. It’s an understandable point of view for those of us who strongly believe in the ethics of a participatory democracy, but our understanding of science itself teaches us something different entirely.

First off, science isn’t merely a group or collection of facts, but rather a combination of two things.

- Science is a comprehensive body of knowledge: one that uses the full suite of all data ever collected by every observation and measurement ever made by all of humanity. This vast suite of knowledge must be treated as foundational, and any new experiment or observation needs to be interpreted in a fashion that’s consistent with everything else we know. Put more simply, science isn’t done in a vacuum, but must take into account every relevant piece of information that’s been gathered.

- Science is also a process, where we continue to interrogate and investigate whatever aspect of the Universe we’re studying in as controlled a fashion as possible. If we want to study the role of any one phenomenon in particular, it’s important to study, quantify, and disentangle all the other effects that could possibly have an impact on the outcome.

What this means is that science, if we wish to conduct it responsibly, must also be evaluated properly. The ability to conduct an expert evaluation is something that requires the very scientific expertise and set of skills that the scientists working in a field cultivate as they progress in their studies and careers. This is why the vast majority of us are wholly unequipped to pass judgment on scientific fields: because we haven’t had the requisite training to become competent in these areas of studies, and we don’t even recognize what common pitfalls we’re likely to succumb to because we lack that expertise.

- Many of us didn’t believe that the hole in the ozone layer was a problem, and even fewer of us understood how hair spray and whipped cream were causing it.

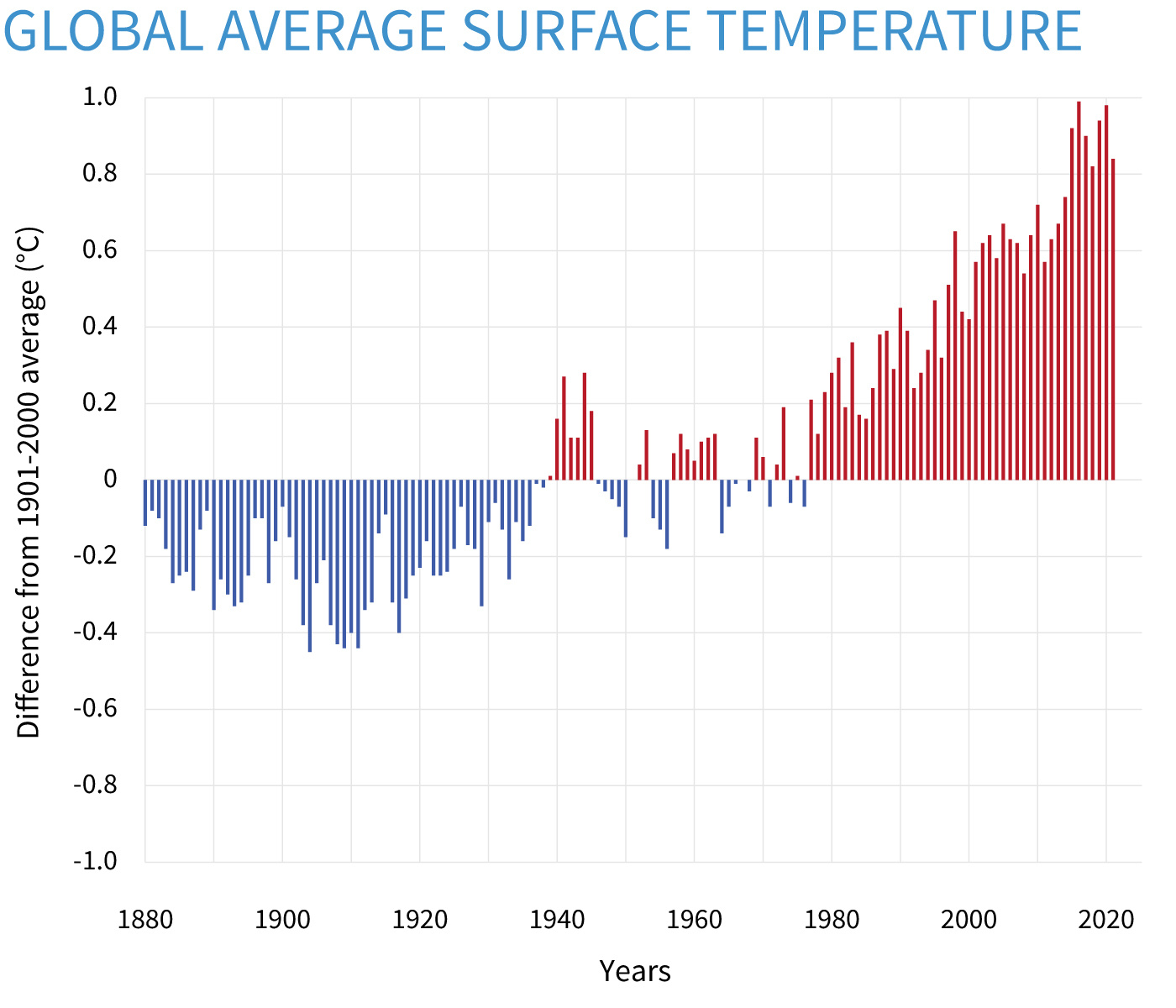

- Many of us still don’t believe that global warming is a problem, and of the ones who do, many don’t believe that a gas as innocuous as carbon dioxide could be the culprit.

- And many of us don’t believe in wearing high-efficiency filtration masks (such as N95 or P100 masks) to prevent the spread of a contagious, airborne disease, despite the disastrous public health outcomes that have already ensued from eschewing that behavior.

Scientists don’t make recommendations because they have a power-hungry desire to tell us what to do. They make recommendations because they are the ones who both know what needs to be done and also know what interventions will accomplish those ends. Science, in particular, tells us how the Universe works and what will happen — albeit with appropriate uncertainties — under a variety of conditions that may occur. Back in the 1600s, Galileo famously wrote that “I do not feel obliged to believe that the same God who has endowed us with senses, reason, and intellect has intended us to forgo their use.” Today, we have obtained the best expert knowledge that we, as a species, have ever been able to obtain, but it’s up to us — the non-experts — to make good use of that information.

4.) Science is immune to even the most legitimate challenges. There are many, many people who bristle at the notion that science can ever be settled, instead preferring to point to the many examples throughout history where newer, better science came along and overthrew the previous consensus idea. However, this has happened less and less frequently as our scientific understanding has continued to improve. The reality is that, today, any armchair challenge that a layperson presents to an accepted scientific theory is going to be dismissed for good reason. This doesn’t mean “you can’t challenge the science,” however. Science not only can be challenged, but actually is challenged all the time: most often by the mainstream scientists who study that particular field. Science not only accepts these challenges, but welcomes and thrives on them, with one big caveat: they have to be legitimate challenges on scientific grounds, where the evidence merits challenging the accepted wisdom.

A scientific theory is only good over the range where it has been established to be valid, and that validity can only be established through experiment, observation, and scientific testing. Whether you’re testing your own theory or someone else’s, the process and procedure is the same. You have to

- make predictions using a particular theory to come up with an expected outcome,

- then perform the necessary experiments and gather the appropriate data,

- and finally, you can compare your results with the theoretical predictions.

This procedure, although coarse in its prescription, is at the core of all meaningful scientific discoveries.

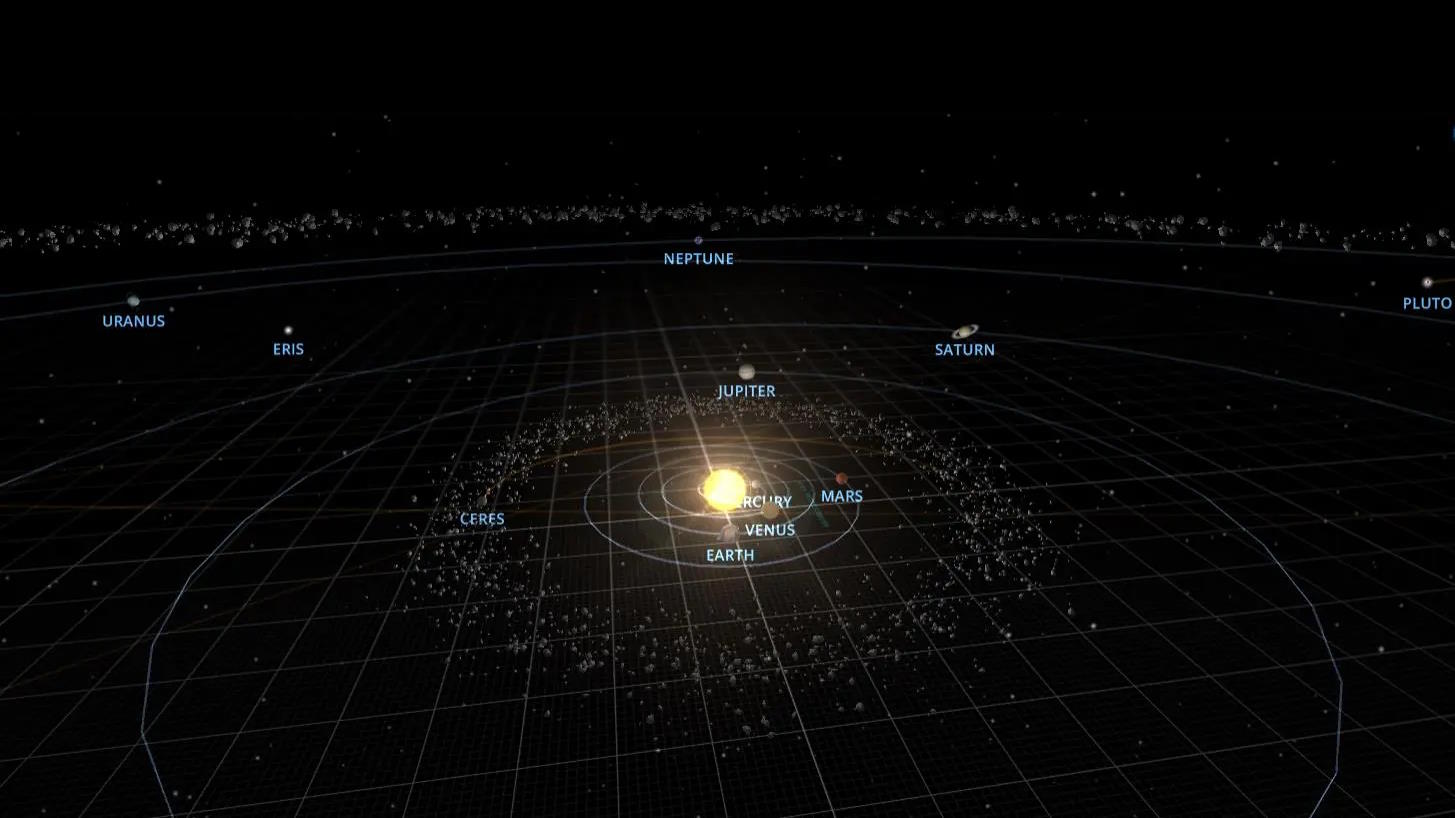

Historical examples abound where exactly these kinds of challenges have brought about numerous scientific revolutions. Einstein’s theories of relativity — both special and general — superseded Newton’s old theories because of their distinct predictions and the fact that critical experiments and observations validated (and agreed with) them and refuted (and disagreed with) Newton’s. The Big Bang, evolution, genetics, and pretty much every leading scientific theory in every field has been challenged innumerable times. A scientific consensus, where there’s no serious opposition to a prevailing theory, can only emerge if the same theory passes practically every test we’ve thrown at it.

The major problem we face, in any realm where we ourselves aren’t the experts, is that we again lack some very important knowledge. We don’t know what challenges have already occurred and what the evidence we’ve collected has led us to conclude. We don’t know the difference between a legitimate and an illegitimate challenge, in the sense that many lines of thought about a topic have already been ruled out on scientific grounds. (We often don’t even know what the various ideas we’re discussing would imply and what results they would lead to if they were true!) Science thrives whenever a legitimate challenge is issued and its implications are investigated. No matter what the outcome is, humanity is always wiser for testing and resolving whatever issues are put before it.

Many of us — perhaps even most of us — have a deep and profound respect for science: for what it is, for what it does, and for what it enables us to learn about the natural world. The challenge we face, however, is one of humility: can we put our own preferences and instincts aside in favor of the evaluations of those with the necessary expertise? When we lack the skills and knowledge required to evaluate a claim that’s being made, will we take the responsible course of action and find someone with the requisite skills and knowledge to show us the light? And if you’re truly committed to finding out the answer for yourself, on your own, will you at least commit to learning and studying all of the necessary background material and information, and to use that information to guide you toward the goal, before you draw your own conclusions?

The fact is simply this: we don’t get to choose our own reality. Reality is what we observe and measure it to be, and while we — as the humans who observe it — may be flawed, the self-correcting nature of science helps eliminate, over time, the very flaws we possess that may bias any initial results or conclusions. We should all be advocating for responsible science that’s as transparent as possible, but similarly, we should accept conclusions that have been reached scientifically as the best approximation to absolute truth that humanity can muster. After all, if we aren’t willing to “trust the science” when it comes to what the Universe tells us when we ask it questions about itself, we throw away the one and only reliable source of truthful information about reality. Those facts, regardless of our personal beliefs or ideologies, are the one thing that we should all be able to agree on.