The 3 key steps to overthrowing a scientific theory

- If you’re sick and tired of the scientific consensus or the prevailing way scientists currently think about and understand the Universe, you’re certainly not alone.

- If you want to replace the current consensus picture with a better one, other scientists will be keen to believe you, so long as you demonstrate your new theory’s superiority.

- Just follow these three key steps: reproduce its successes, explain what it cannot, and make new predictions that differ and can be tested.

Science, like many things in life, is always a work-in-progress. While a successful scientific theory has questions it can answer, natural phenomena it can accurately describe, and robust predictions it can make, it’s also fundamentally limited at any point in time. Any theory, no matter how successful, has a finite range of validity. Stay within that range and your theory works very well to describe reality; go outside of it, and its predictions no longer match observations or experiments. This is true for any theory you pick. Newtonian mechanics breaks down at small (quantum) scales and high (relativistic) speeds; Einstein’s General Relativity breaks down at a singularity; Darwin’s evolution breaks down at the origin of life.

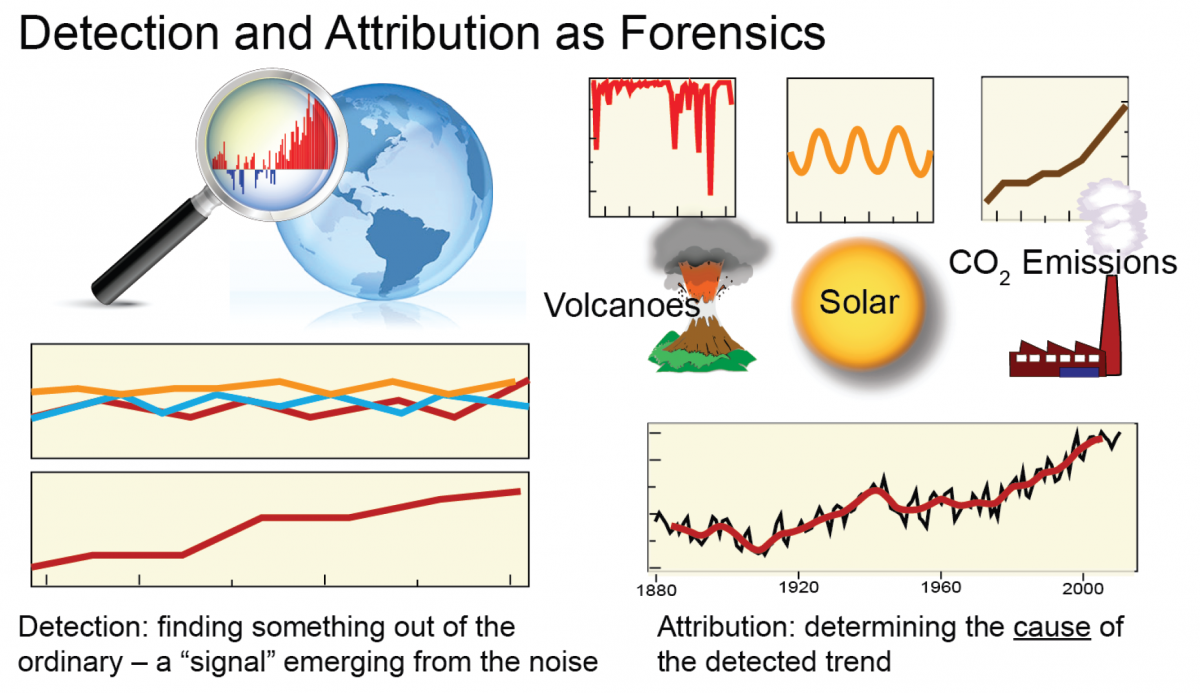

But the models we have today are known to only be our best approximations of reality. Somewhere, if we look hard enough, we’ll find where the limits of even our best theories lie, and find evidence that contradicts the prevailing theory’s best predictions. When we come upon a better theory that gets it right, where we can hold that new theory up against our old theory and can compare their predictions, one against the other, and the new theory scores an overwhelming victory, that’s usually the precipitating event for a scientific revolution. It’s happened before, and we can be certain it’ll happen again.

The prerequisite

If you hope to supersede the current, best theory we have, and this is true in any scientific discipline, you have to honestly recognize the present successes, failures, and limitations of your theory. Every theory that we have makes predictions, but there’s a limit to what they can successfully predict. So long as that’s the case, there will always be the option for a better, more complete, more fundamental theory to help us understand the Universe.

The proverbial holy grail of scientific theories is what’s called a final theory of everything. This was Einstein’s ultimate dream, and remains the dream of many other scientists across a variety of fields. Such a theory would predict all natural phenomena in the Universe given any initial setup and conditions. You could calculate the outcome of any experimental setup in advance; you could predict how any system would evolve arbitrarily far into the future. The only limitation you’d face would be from not having an arbitrary amount of computational power, rather than any theoretical limitations.

But let’s be honest about what we know and do not know today: we have not arrived at that point. We do not have a working theory of everything; we have a slew of very successful theories, each one of which is fundamentally limited in its scope. In every field, we have phenomena we can observe or experiments we can design where the predictions of our best theory either contradict the data or yield nonsense. In addition, there are often problems or puzzles that cannot be explained with the theories we have.

- Why do neutrinos have mass?

- Why does the Universe consist of large amounts of matter but not antimatter?

- What happens to the gravitational field of an electron as it passes through a double slit?

- And why do the fundamental constants have the values that they have?

An unexplained phenomenon that is observed, but doesn’t have a theory to predict it, is often the impetus for a scientific revolution. This has to be the default starting point: the point at which all scientists in all disciplines can come to the table and say, “Yes, I agree that this is where we begin our investigations.”

Step 1: Your new theory must reproduce all the successes of the leading theory.

So, you’ve got a new theory that you hope will supplant the presently leading one? Great! Your first order of business is to demonstrate that your new theory doesn’t fail where the old one succeeded. The more successful the prevailing theory, the taller an order it is to meet this goal. For example, if you wanted to supersede our current theory of gravity: Einstein’s General Relativity? You’ve got to explain:

- gravitational lensing,

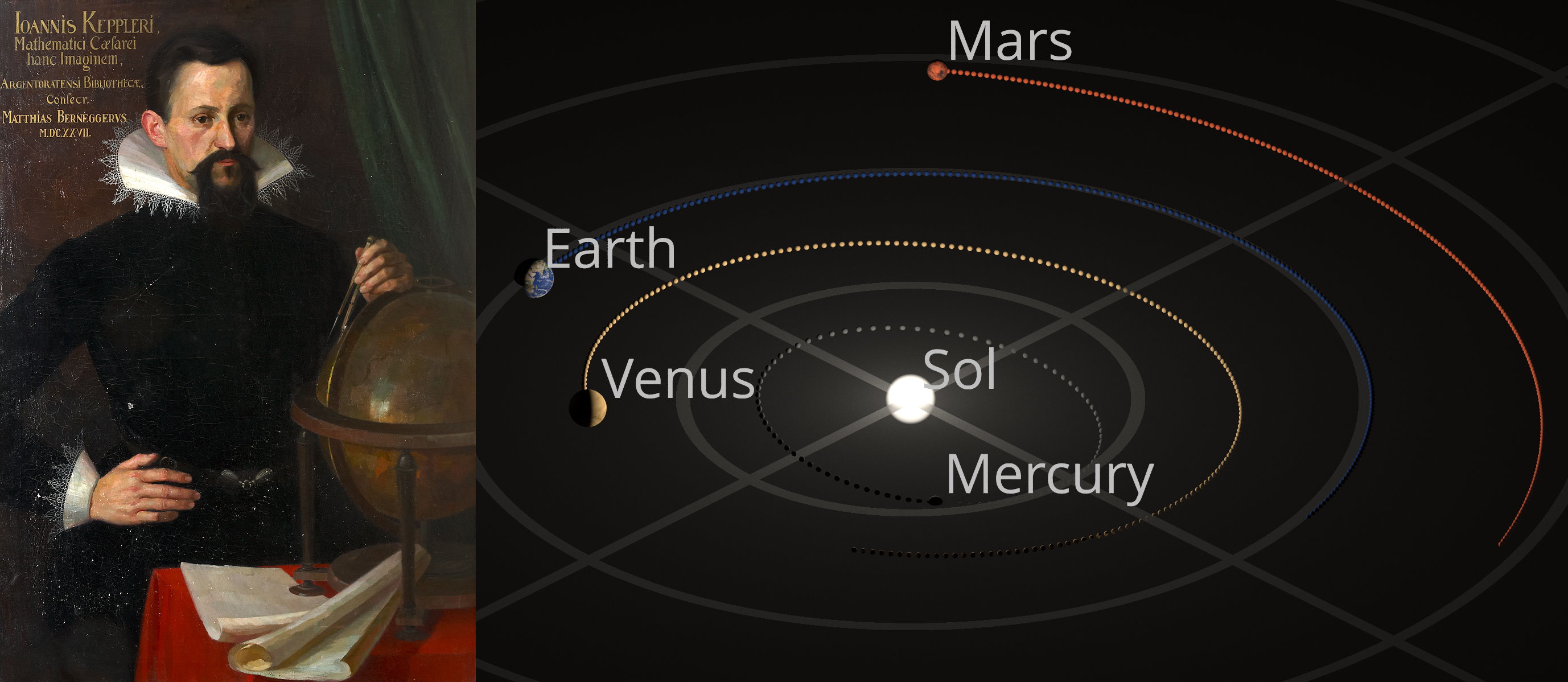

- the precession of Mercury’s orbit,

- the Lense-Thirring effect,

- gravitational redshift,

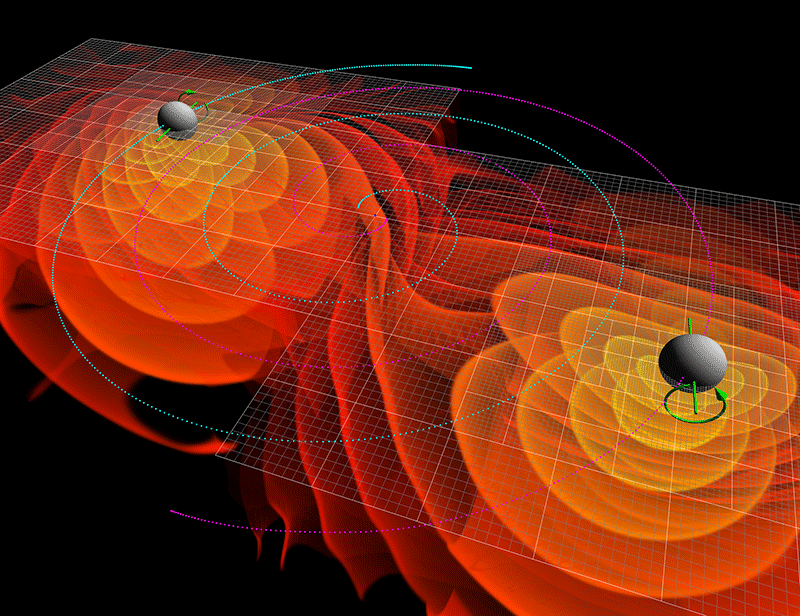

- the decay of binary pulsar orbits,

- the Shapiro time delay,

- and gravitational wave signals from merging black holes and neutron stars,

along with many other experimentally verified realms where General Relativity has been validated. From tabletop experiments on Earth to Solar System-scale experiments to Universe-scale measurements of galaxies, galaxy clusters, and the cosmic web, your new theory has to do at least this well: succeed where the leading theory has already succeeded.

The same thing is true if you wanted to go beyond Darwinian evolution. Yes, Darwin’s theory has its limitations, but it does an exquisite job of explaining a great number of observed phenomena, including:

- the emergence of biological diversity,

- the responses of organisms to various selection pressures,

- and the inheritance of traits among child organisms from their parent organisms,

as well as many others. Your first step, if you want to supersede Darwinian evolution, is for your theory to also achieve equally satisfactory explanations for all of these.

Similarly, if you were determined to improve on the Bohr model of the atom, you’d have to reproduce its successes, including:

- explaining the various energy levels within an atom,

- explaining the scattering experiments that show the presence of an atomic nucleus,

- and the spin-orbit interaction of the electron with the atomic nucleus,

among others. These feats are not necessarily easy to achieve. Additionally, this also means your new theory cannot make new predictions that contradict observations that have already been made or experiments that have already been performed. It isn’t enough to get a selection of these predictions right; you have to reproduce every single success of the prior theory. If you can’t equal what you’re trying to replace, you won’t surpass it.

Step 2: Your new theory must succeed where the prior theory does not.

It’s true that theorists play in the sandbox all the time: even if our current explanation is 100% satisfactory, we’re always looking for new solutions to old problems. This kind of tinkering can often pave the way for a scientific advance down the road, where a critical point is reached: where there’s some sort of conflict or gap between what we theoretically expect to see and what we’re actually observing.

We’re only ever able to discern whether one theory is better than another theory, however, by contrasting them against one another and testing which one better matches what’s occurring in the real world. This usually requires a motivation; for someone to look at the data and notice that our predictions weren’t matching up with reality.

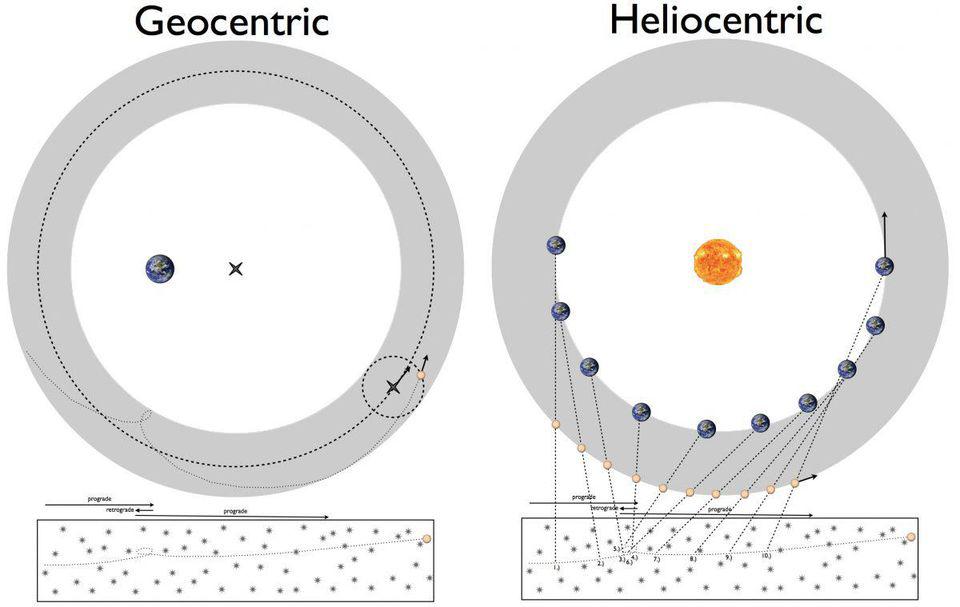

When this occurs, it’s natural to suspect that something isn’t right with the old theory; there’s something it simply fails to explain. Newtonian physics couldn’t explain the mechanics of fast moving particles; the ray theory of light couldn’t explain interference patterns; the universal law of gravitation couldn’t account for Mercury’s orbit.

All of these puzzles led to many new ideas which would explain these phenomena, but not every idea could also reproduce the pre-existing successes. For example:

- A hypothetical planet interior to Mercury — dubbed Vulcan — was proposed by Urbain Le Verrier to explain Mercury’s anomalous orbit.

- Other scientists proposed that the Sun’s corona was massive, and impacting the motion of Mercury.

- Another team, Simon Newcomb and Asaph Hall, determined that if you replaced Newton’s inverse square law, which says that gravity falls off as one over the distance to the power of 2, with a law that says gravity falls off as one over the distance to the power of 2.0000001612, you could explain Mercury’s motion.

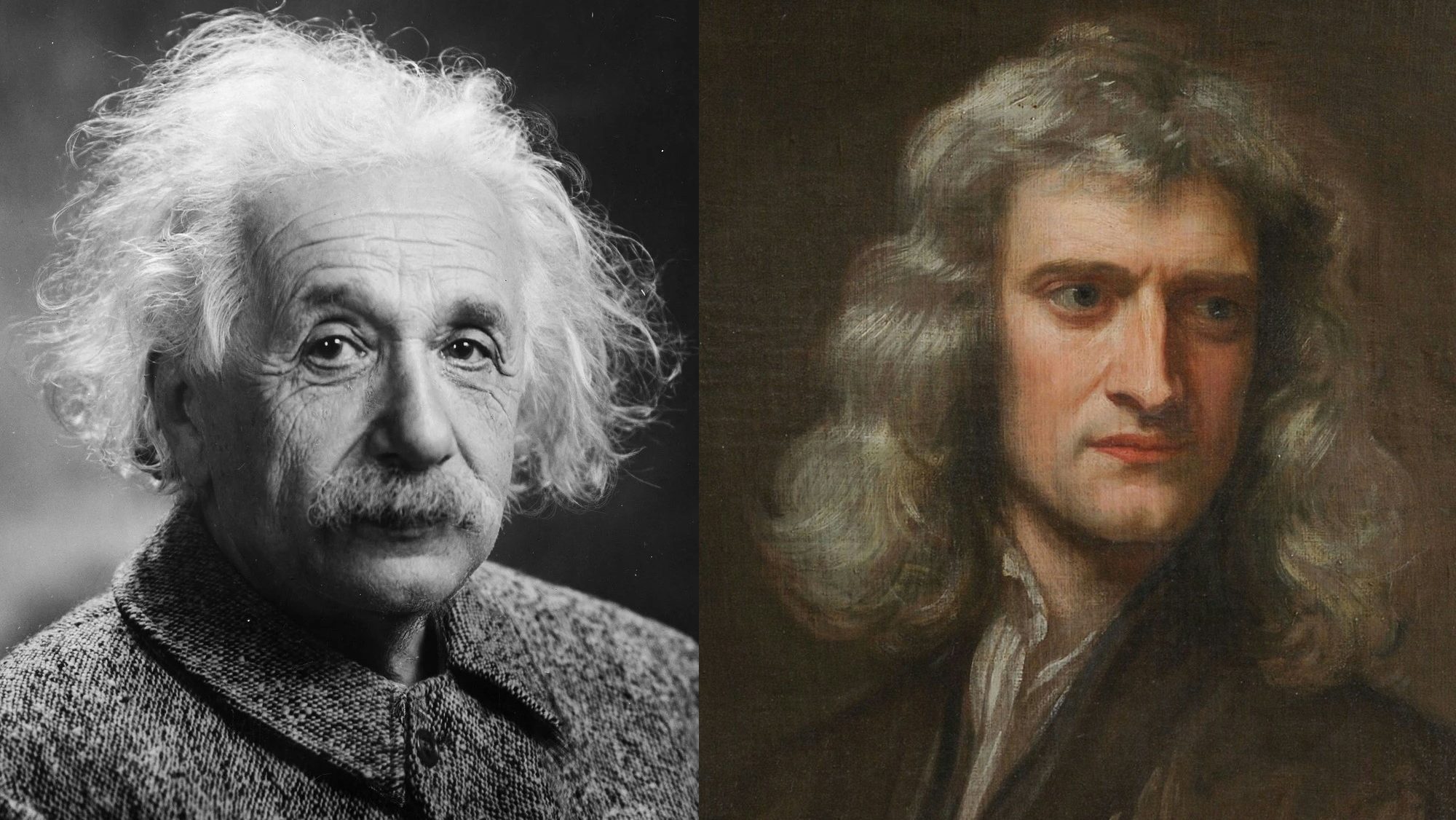

- Finally, Einstein did away with Newton altogether, replacing his gravitational “action-at-a-distance” with curved spacetime.

All of these ideas were seriously considered for many years; this is part of why steps 1 and 2 aren’t enough on their own. If you want to establish which of the theoretically possible explanations actually best reflect the real universe that you inhabit, you have to confront your ideas with the all-important third step.

Step 3: Your new theory must make new, testable predictions that differ from those of the original theory.

Each one of these ideas for a new theory of gravity or massive phenomenon in the inner Solar System would have observable consequences: consequences that would distinguish them from not only one another, but from the prevailing, older theory of Newtonian gravity.

- If there were a new planet interior to Mercury, it should have been detectable with a telescope.

- If the Sun’s corona were massive, we should detect a greater particle/matter density than would be consistent with observations.

- If Newcomb & Hall’s theory of gravity were correct, it would affect the observed orbits of the Moon, Venus, and Earth in ways that do not match with observations.

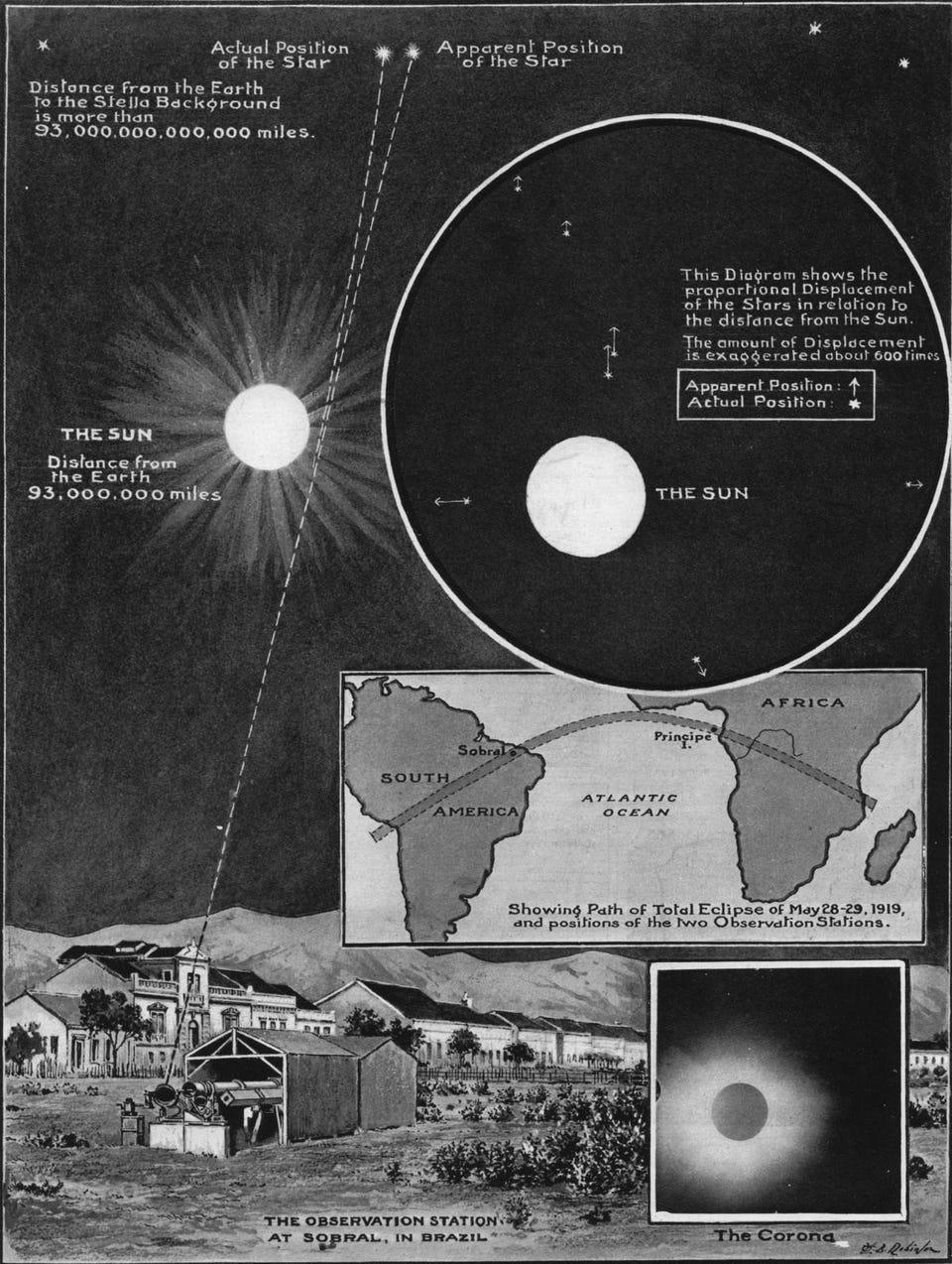

- And if Einstein were correct, it would have meant that, with space being curved by mass, that a background light source should follow a curved, rather than a straight, path.

In fact, according to Einstein’s General Relativity, it became possible to calculate, for any mass at all, exactly how severely a light-path would be curved-and-bent. There’s one very large mass in our Solar System, in fact: the Sun. If Einstein’s predictions were correct, a total solar eclipse could prove to be the perfect time to test it. How much would a background point-of-light, like a star, be bent by the Sun’s gravity?

- Would it curve according to the amount General Relativity predicted?

- Would it curve by a null amount, since light has no mass and should experience no Newtonian attraction?

- Would it curve by the amount you’d get in Newtonian gravity if you assigned a photon a mass-equivalent given by its energy: through Einstein’s E = mc²?

In 1919, during a total solar eclipse, this prediction of Einstein’s was put to the critical test. In very short order, the results were published and looked extremely strong: light bent according to Einstein’s predictions, and definitively not according to the predictions of any of the alternatives that had been put forth. In a tremendous revolution, we had a new theory of gravity, put to the test many times over the past 104 years, and passing that test wherever the observations or experiments were of high-enough quality.

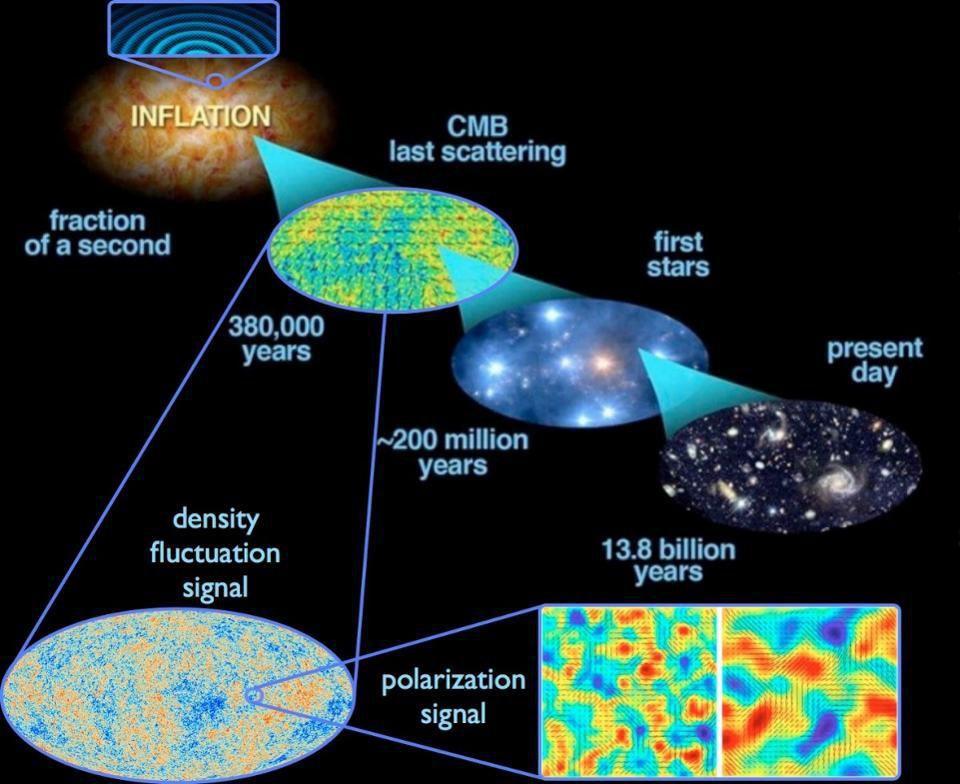

It took similar theoretical developments and experimental/observational confirmation to arrive at all of our leading scientific theories, from genetics and DNA to the Big Bang, cosmological inflation and dark matter. These aren’t our greatest theories because the math is so pretty or they match our intuition so well, but because they describe the natural phenomena that we actually observe in this Universe so successfully.

As science becomes a more developed, evidence-rich enterprise, it becomes a more herculean task to create a single theory that explains the full suite of data. Yet that’s exactly what the most successful theories do: explain so much of that data in such great detail over an extremely large range of validity. However, we must always keep this in mind: no matter how successful an idea has been in the past, all it takes is one inconsistent observation to throw the whole thing into doubt. Our greatest scientific theories of today will most likely all be superseded someday in the future, particularly as new and superior evidence is gathered.

Massive neutrinos are a hint of physics beyond the Standard Model; the black hole information paradox is a hint of gravity beyond General Relativity; the facts that atom-based matter exists and that life arose from it are undeniable, but where that matter (and not an equal amount of antimatter) came from and how life arose from it are still both great unknowns. These puzzles and paradoxes, along with many others, may serve as harbingers of an eventual, perhaps even monumental, scientific advance. Until then, we can only speculate at the frontiers of science, in our attempts to take these three massive steps toward a better understanding of the Universe.